Lori Beth De Hertogh, James Madison University

(Published, August 1, 2018)

Digital media are not always there. We suffer daily frustrations with digital sources that just disappear. Digital media are degenerative, forgetful, erasable.

—Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, “The Enduring Ephemeral, or the Future Is a Memory”

In her widely read New York Times article “Wikipedia’s Sexism Toward Female Novelists,” Amanda Filipacchi illustrates the fragility of women’s online work, noting that in 2013 Wikipedia editors began moving women “one by one, alphabetically, from the ‘American Novelists’ category to the ‘American Women Novelists’ subcategory.” Filipacchi points out that male novelists remained in the American Novelists category, no matter how obscure their work. In short, Wikipedia’s iterative process of updating their categorization system propagated gendered biases that, as Filipacchi describes it, “ghettoized” women’s work by labeling it as less valuable (Sexism on Wikipedia). This example illustrates that while digital spaces make the contributions of marginalized groups more accessible, they also make them more erasable.

Digital media are, as Wendy Chun suggests, “degenerative, forgetful, erasable” and at risk of simply vanishing (192). The disappearance of women’s artifacts is especially troubling because women’s contributions have long been rhetorically marked as inconsequential and, therefore, have often escaped “the notice of historians” who have traditionally focused on “the works of great men” (Durack 251). The increased risk of erasure for artifacts produced by women and other marginalized groups means that feminist digital archivists must take extra measures to ensure that these artifacts are carefully preserved.

One way to contend with digital erasure is by employing a methodology I call feminist rhetorical iteration. This methodological orientation attends to the ways that digital iterations—or the process by which digital content shifts and evolves from one digital space, format, or version to another—can destabilize and erase digital content. Building on Tarez Samra Graban’s notion of “locatability,” or the “the fluid relations and circulations or pathways of texts” (Graban 174), I argue that feminist rhetorical iteration is a digital archival approach that can help feminist archivists contend with the “daily frustrations” (Chun 192) associated with curating, storing, and preserving digital artifacts. I draw from my own experiences in building a digital archive for an organization I founded and direct called Feminist Scholars Digital Workshop to argue for this methodological reorientation and to demonstrate how it can be applied to digital archival endeavors. I use these experiences to offer practical interventions that feminist rhetoricians, or any scholar engaged in digital archival work, can use to navigate the mutability of digital objects and their associated data.

Feminist Scholars Digital Workshop (FSDW) Online Archive

Founded in 2013, Feminist Scholars Digital Workshop (FSDW) is an online, international workshop for individuals working on feminist research projects. The workshop, sponsored by HASTAC (Humanities, Arts, Science, and Technology Alliance and Collaboratory) and James Madison University, brings together diverse scholars from around the globe. Throughout the workshop, participants collaborate in small groups to exchange feminist research projects (e.g., articles, webtexts, syllabi, proposals, artistic pieces) for feedback and peer review. Peer review groups are interdisciplinary and encourage feminist mentorship by bringing together scholars with varying levels of experience and expertise. The workshop relies on platforms such as Google Docs, ZeeMaps, HASTAC forums, and Slack to facilitate peer review and feminist networking. Since its inception, participants have used these platforms to produce a wide range of feminist artifacts from social media posts to work-in-progress projects to blog posts.

As the workshop’s founder and director, I have spent the last five years creating a private, informal archive of workshop content using platforms such as Evernote and Google Drive. This online archive includes artifacts such as promotional materials (e.g., digital posters, flyers, banners), web-based content (e.g., information about the workshop, Google Docs, workshop programs), and interactive content (e.g., maps of participant locations, keynote speaker videos). Recently, I shifted from an informal archive designed to meet my own administrative needs to a publicly-available, digital archive that tells the story of the workshop and its participants. This shift was driven by a number of factors, including participant requests to access materials, the need to give external audiences (such as grant and tenure committees) access to content, and the desire to create a “living” digital archive of feminist work.

Figure 1. FSDW Online Archive

The Digital Archive: Challenges and Definitions

Building the FSDW archive has been a challenging process largely because a number of workshop artifacts have been significantly altered over the years (or, in some cases, have vanished altogether) as they have undergone digital iterations, or the process by which digital content shifts and evolves from one digital space, format, or version to another. For example, artifacts such as blog posts, tweets, and webpages have been overwritten as new content replaced older versions. Such digital iterations make it difficult to preserve workshop materials and build an archive that represents the full range of artifacts produced by participants and organizers.

I use the term digital iteration to describe the technological and rhetorical evolution of digital artifacts as they move from one digital space or version to another. This term builds on Jay Bolter and Richard Grusin’s notion of remediation, which they describe as the process by which one medium transitions (or is remediated) into another. Examples of remediation abound: speeches turned into written texts, newspapers transformed into webpages, stage performances reproduced for the screen. Remediation, however, is not simply about the movement from one medium to another; it also concerns the improvement of an object as it evolves. Susan Delagrange suggests that remediation “is usually considered to be ‘progressive,’ in the sense that the customary movement is from older to newer, ‘better’ media” (24). Phill Alexander et al. offer a similar definition, indicating that remediation “is an act that calls upon composers to reflect, resituate, and reshape a piece while moving it to another medium, and often to enhance or expand upon its existing meaning” (31-32).

I want to draw an important distinction between these scholars’ conceptualization of remediation and how I expand this concept to theorize digital iteration. While these scholars focus on how a medium is represented and improved upon within a new one, I use the term digital iteration to theorize movements and repetitions that occur within the same digital mode or medium. The etymological heritage of these terms further illustrates such points of departure: The word remediation comes from the Latin remediātiō meaning to “remedy” or “heal,” while iteration derives from iterāre, meaning to “do again” or “repeat.” Unlike remediation, iteration is not a transformation into a new mode or medium, but is instead a repetition and, typically, an improvement upon the original mode; it is this process of repetition, reversioning, and reproduction that makes iterated objects vulnerable to destabilization and erasure.

Let me offer an example. In 2015, one of the workshop’s sponsors (HASTAC) decided to transition to a new content management system to offer users a more mobile-friendly and streamlined browsing experience. In theory, all content on the original system would safely migrate to the new one. But shortly after the migration process was complete several workshop pages were replaced with the ominous warning:

Figure 2. “Page Not Found”

As the above screenshot reveals, HASTAC’s transition from a “previous version” to a “new and improved site architecture” erased a digital object. In “Can the Internet be Archived?,” Jill LePore describes this as “link rot,” or the decay of digital objects over time (36). The use of the word “rot” is not melodramatic—after all, the majority of web users want the most recent, up-to-date content available and not old, “rotting” bits of outdated information. This almost universal preference makes older media objects vulnerable to erasure as fresh content and technologies arrive on the scene.

Consider, for example, Storify’s recent “end-of-life” announcement. A webtool for curating social media content such as hashtags and tweets, the program’s software developers announced in 2017 that they were “no longer allowing new users to sign up and will end existing users’ access to Storify.com.” This decision was likely driven by a number of factors, including loss of profitability and the launch of newer digital curation tools such as Twitter’s “threading” feature.

Figure 3. Storify Update

For digital archivists, the loss of a curation tool like Storify—and, more importantly, its associated digital data—is more than a minor inconvenience. For example, in 2014 and 2017 FSDW organizers used Storify to create micro-archives of participants’ tweets. Storify’s announcement that “accounts and their content will no longer be accessible” means that these micro-archives will be either destroyed or significantly altered if exported into a new mode or format. In other words, these feminist artifacts will become invisible as they undergo digital iterations.

As I built the FSDW archive, the process of thinking about iterative activity such as HASTAC’s “page not found” and Storify’s “end-of-life” announcement shifted my focus from thinking about what I needed to archive to considering the methodological assumptions and technological tools that undergirded my archival values and practices. Until this moment, I had focused on gathering the artifacts themselves—on taking screenshots, saving URLs, and documenting activity logs. But moments like discovering the “page not found” message and Storify’s “end-of-life’ announcement made me realize that iterative activity needed to be accounted for in my curatorial practices, and that I (and perhaps other digital archivists) required innovative strategies and tools for such a process. As I illustrate in the following section, digital archival and curatorial practices are enhanced by methodological orientations like feminist rhetorical iteration, an approach that calls our attention to the technological iterations that can modify or obscure feminist work as it is iterated across the web. By making these processes visible, we are able to examine the digital and rhetorical pasts of archival objects and consider ways we might track and record future shifts and evolutions, even if an artifact is no longer extant.

Accounting for Digital Iterations in the FSDW Online Archive

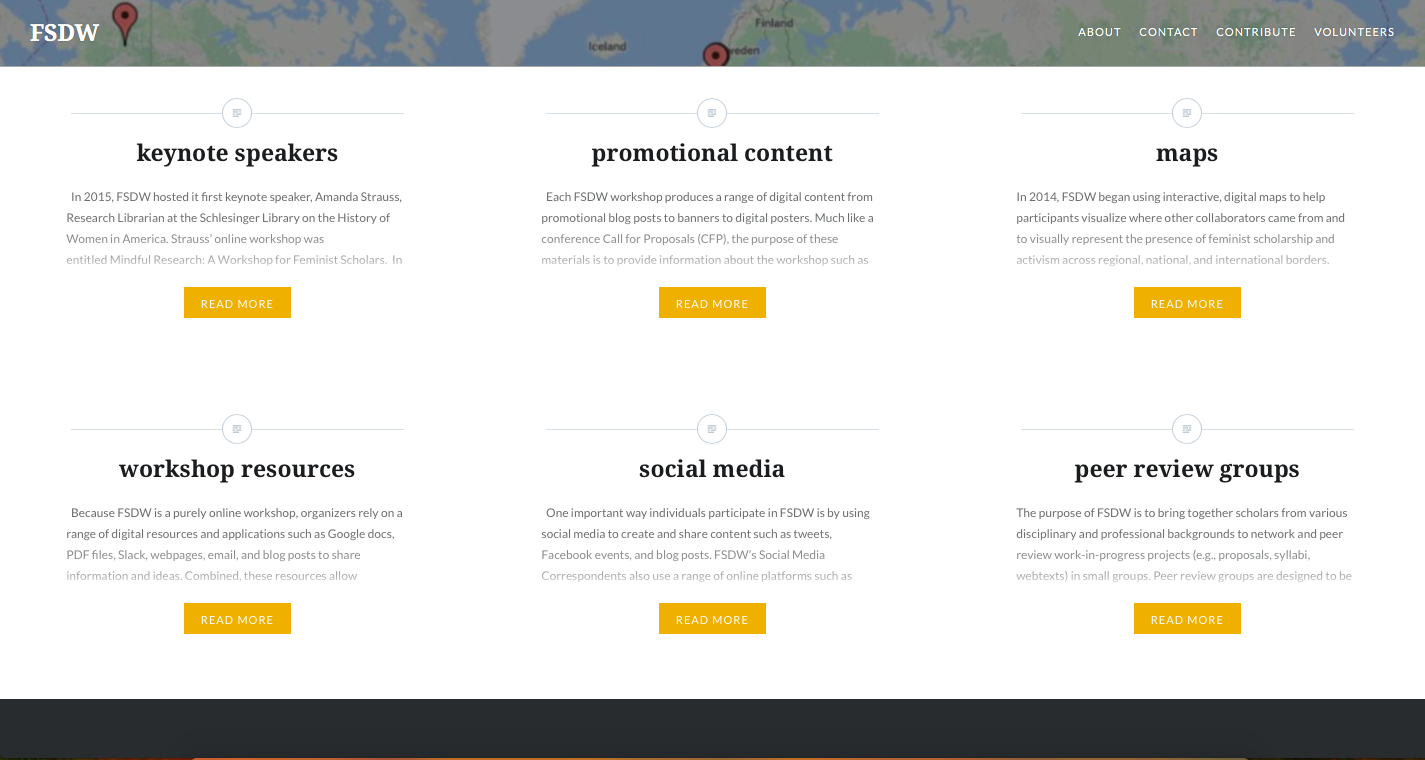

When I began building FSDW’s archive, I had two goals in mind. The first was to collect, tag, and organize as many artifacts as possible. The second was to preserve these artifacts in ways that guarded against erasure and destabilization. As shown in the screenshot below, I organized content according to six different categories: keynote speakers, promotional content, maps, workshop resources, social media, and peer review groups.

Figure 4. FSDW Archival Categories

Participants bring a range of feminist artifacts to the workshop such as work-in-progress projects (e.g., documentary films, articles, syllabi) and produce a variety of communications in online spaces including Slack, Twitter, and Google Drive. To protect participants’ privacy, I included in the archive only publicly available content such as announcements, programs, public blog posts, and social media content. To determine what kinds of content to curate, as well as how to design the archive, I turned to archival models such as the Feminisms and Rhetorics’ “Past Conferences and Calls” webpage, a resource that houses artifacts such as conference programs, Storify collections, retrospectives, and calls for papers. I also closely studied Rise Up!, a digital archive of feminist activism in Canada from the 1970s to the 1990s, and the Jewish Women’s Archive, which “documents Jewish women’s stories, elevates their voices, and inspires them to be agents of change.”

These and other digital archives served as models that helped me make rhetorical and organizational decisions about how to curate and present multimedia objects. But because these models largely rely on traditional archival practices (i.e., displaying original, primary media objects) for the recovery and preservation of women’s artifacts, they did not help me develop an archival strategy that addressed the ways digital iterations could destabilize the very objects I was working so hard to preserve.

To theorize the impact of iterative activities on the FSDW archive, I turned to Tarez Samra Graban who suggests that digital archival work is further enriched not only by mapping the location of archival artifacts, but also by tracking the complex relationships, pathways, and connections among archival objects. In other words, locating and preserving artifacts is only one step in the archival process; the other is tracing the rhetorical contexts and ecologies feminist artifacts circulate within. She argues that this kind of archival reorientation shifts us from focusing exclusively on the location of objects and toward recognizing the digital archive as an assemblage of ideas where artifacts circulate in complex rhetorical ecologies.

Graban’s notion of the archive as a digital assemblage can be mapped onto an archival situation like the “page not found” example I provided earlier in interesting ways. For instance, while this example demonstrates how digital iteration erased a media object, the remaining metadata (such as the number of times the page was viewed, how many times it was “liked,” and even the “page not found” statement itself) reveal that iterative aspects of the artifact remained in circulation as part of an epistemological assemblage of ideas. As Graban observes, this kind of ancillary data is sometimes the only information a feminist archivist might have access to.

Graban’s approach toward understanding artifacts as objects that are locatable through their metadata, pathways, and movements can be deployed to help us think about the need to collect the hidden or invisible features of iterated objects, such as the number of times a viewer interacted with the object, source code, or interface features. What feminist rhetorical iteration offers is a way to “unmute” (Graban 174) invisible digital elements and iterative activities, a process that can lead to more sustainable archival practices and enhance our ability to understand the rhetorical ecologies and gendered contexts digital objects circulate within.

Preserving Source Code as Feminist Archival Intervention

Later in this article, I consider how certain kinds of archival tools position feminist archivists to cope with the iterative, dynamic nature of digital objects. But before we can select appropriate tools, we must first consider what exactly feminist archivists should be capturing and what kinds of hidden or invisible digital elements we must concern ourselves with. I suggest that source code, or the instructions that tell a computer program how to function, should be chief among the digital data we curate and preserve. Without source code, it is almost impossible to recreate a digital artifact should it decay or become inaccessible. We must, therefore, move beyond collecting what is at “the surface of our screens” (McPherson) and toward gathering the behind-the-scenes data that underwrite media objects.

For example, consider the recent move of the online map provider ZeeMaps to limit users’ access to map data. In a 2018 email announcement, platform developers informed users that “we will be limiting views on maps not owned by an active paid plan to 100 map views.” This announcement is problematic for FSDW because the workshop relies on maps as an interactive tool for participants and as a means of digitally archiving participant locations for each workshop year. Moreover, because we operate on a limited budget, we are unable to upgrade to a long-term paid plan for these types of online resources.

Figure 5. 2017 FSDW ZeeMap

In an effort to maintain permanent and unmitigated access to FSDW’s ZeeMaps, I have downloaded and archived source code into the FSDW archive for each year’s map. Although this is an imperfect solution because it falls short of delivering full access to the maps and their data, it does offer some protection against what Stefano Zacchiroli calls “digital decay.” Zacchiroli, co-founder of Software Heritage, argues that archivists should contend with digital decay by preserving source code, or the coding information that underwrites digital objects. He suggests that source code safeguards against the “permanent loss of digital information” and is “essential for preserving our cultural heritage.”

I extend Zacchiroli’s work to argue that source code is needed not only to preserve digital objects in and of themselves, but also to give us critical information about the rhetorical contexts and ecologies these objects were designed and rendered within. While a number of industry specialists have argued that coding languages are neutral forms of communication that simply execute operational commands, feminist and critical race scholars have demonstrated that racial and gendered biases are embedded in these languages. In her oft-cited work, “Why Are the Digital Humanities So White? Or Thinking the Histories of Race and Computation,” Tara McPherson argues that there are deep “parallels between the ways of knowing modeled in computer culture” and socio-cultural and epistemological shifts in how we think about race, sexuality, and gender. More recently, award-winning MIT graduate student Joy Buolamwini demonstrated that the algorithms that power facial recognition software often fail to “identify a broad range of skin tones and facial structures,” which, as Buolamwini puts it, can “lead to exclusionary experiences and discriminatory practices.” What these and other scholars illustrate is that digital elements like algorithms and source code are deeply rhetorical and “can reflect, or even amplify, the results of historical discrimination” (Kirchner).

With this in mind, I argue that source code must be part of the networks of activity and assemblages that feminist archivists attend to in our methodological practices. To return to my own experience with FSDW, an early mistake I made in building a personal, informal archive was failing to save source code from artifacts like webpages and blog posts; this error later cost me the ability to “defend against format obsolescence” (Castagné 1), recreate these objects in their native formats, and study the rhetorical and cultural patterns embedded in their coding.

I learned from this experience that it is essential to collect and preserve multiple pathways, versions, and iterations of digital objects so that we maintain access not just to the objects themselves, but also to the rhetorical assemblages and digital landscapes they circulate within. As a methodological approach, feminist rhetorical iteration can serve as a guide for making these types of archival decisions and for drawing our attention to the need for distinctly feminist interventions into the technological and rhetorical spaces that mediate the movements of digital objects.

Contending with Digital Iterations via Webrecorder

There are a number of tools and approaches feminist archivists might use to intervene in the digital evolutions that destabilize digital work. One such tool is Webrecorder, an online archival resource that, according to the project developer’s website, helps users “create high-fidelity, interactive web archives of any web site.” Webrecorder developers argue that unlike other digital preservation solutions that focus on static documents like HTML pages, their software captures “dynamic content, such as embedded video and complex javascript.” The significance of a tool like Webrecorder is that users can create “interactive web archives” that include dynamic and alterable web elements (e.g., content blocks, color schemes, logos, and layouts) in a variety of digital spaces such as social media sites, video platforms, and web-building applications.

Figure 6. Webrecorder Homepage

Tools like Webrecorder signal an archival shift away from collecting static documents and toward capturing interactive and mutable digital objects; such a shift disrupts traditional notions of the archive as a place where discrete, stable artifacts are contained. This methodological reorientation to the archive positions us to be more attuned to a fluctuating digital landscape where locating objects may or may not be useful—or even possible. At a 2017 workshop at the Conference on Community Writing, Graban suggested that we can attend to this kind of evolving digital landscape not only by collecting and preserving historical records, but also by tracing the various connections among archival objects so that we can better understand the relationships among them.

I extend Graban’s work to suggest that applications like Webrecorder can, indeed, help us account for these networks of relationships. But just as importantly, combining these tools with methodological approaches like feminist rhetorical iteration allows us to recognize iterative activities and respond to such movements and assemblages. Consider, for instance, my earlier description of HASTAC’s migration to a new content management system and how this iterative process erased a workshop webpage, along with its accompanying metadata (e.g., source code, tags, user profiles). Had I used an iteratively-oriented tool like Webrecorder, the disappearance of this page might have been negligible. Instances like these illustrate the need to better understand both “the tools that mediate archival creation and curation” (Lewis) and the methodological interventions feminist archivists need to thrive an ever-evolving digital landscape.

The Future of Digital Feminist Archives

Feminist archivists and historiographers might be reluctant to engage in archival practices such as gathering source code or tracking technological iterations across platforms and applications; after all, these can be highly technical activities that might be intimidating to scholars who are more accustomed to analyzing digital artifacts than to collecting the codes that underwrite them. As a result, scholars working in the field have traditionally focused on issues around access to and recovery of women’s artifacts, without enough consideration as to how digital iterations rewrite and destabilize digital feminist objects. Scholars in the field, then, must work to further theorize technological and rhetorical shifts like digital iterations and respond to such shifts by developing and employing digital tools that allow for feminist interventions into archival spaces. Jessica Enoch and Jean Bessette stress the prudence of such a shift, noting that it offers “the opportunity to explore new possibilities for movement and meaningful engagement” as well as a means to “participate not only on the user end of digital tools but also in their production” (654).

Unfortunately, the efforts that go into building and maintaining digitally responsive archives are often undervalued by academia and end up falling into the realm of the kinds of caretaking work women have long done for little pay or professional recognition. My work in building and maintaining the FSDW archive (as well as directing the workshop since its inception in 2013) is considered service to the profession and, while recognized and appreciated by my current institution, will not play a significant role in the tenure process. In other words, while the kinds of feminist interventions into the archives I call for here are needed, they will inevitably be mediated and, in some cases, mitigated by the institutional values an individual archivist finds herself within.

Another challenge underpinning the kind of methodological reorientation I call for here is finding the balance between collecting enough data to account for iterative processes, but at the same time recognizing that we cannot preserve everything. In a panel presentation at the 2017 Feminisms and Rhetorics conference, Alexis Ramsey-Tobienne wisely asked: “are we losing anything in this drive to save it all?” Fully addressing her question is beyond the scope of this article, but I share her concern that the push to save it all might mean we are setting ourselves up to inadequately parse and process artifacts in ways that are useful to stakeholders. In other words, the process of gathering digital data and of making that data scalable, accessible, and useful are not one and the same. With that in mind, I suggest that feminist rhetorical iteration should be taken up in ways that are responsive to the exigencies of the individual archivist. While in my own case preserving a broad range of digital elements and metadata for FSDW has been both possible and fruitful, this approach might not be suitable for more expansive projects or for archivists working with limited support and resources.

Finally, some scholars argue that in the era of Web 2.0 we must accept that digital artifacts are, to some extent, no longer preservable and that we should shift our attention from traditional notions of preservation and toward understanding digital archives as ephemeral. Joy Palmer, for example, argues that “[t]he emergence of Archives 2.0 is less about technological change than a broader epistemological shift which concerns the very nature of the archive, and particularly traditional archival practice which privileges the ‘original’ context of the archival object.” Palmer makes a valid point concerning the evolving nature of online archives. But I remain convinced that there is a critical need to seek out new ways to preserve the “original context” of digital artifacts. Without doing so, we normalize the technological and rhetorical exigencies that will continue to erase feminist work.

Alexander, Phill, et al. “Teaching with Technology: Remediating the Teaching Philosophy Statement.” Computers and Composition, vol. 29, 2012, pp. 23-38.

Bolter, Jay, and Richard Grusin. Remediation: Understanding New Media. MIT Press, 1998.

Buolamwini, Joy. “How I’m Fighting Bias in Algorithms.” TedTalk. November 2016, http://www.ted.com/talks/joy_buolamwini_how_i_m_fighting_bias_in_algorithms.

Castagné, Michel. “Consider the Source: The Value of Source Code to Digital Preservation Strategies.” SLIS Student Research Journal, vol. 2, no. 2, 2013, pp. 1-10. http://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1069&context=slissrj

Chun, Wendy Hui Kyong. “The Enduring Ephemeral, or the Future Is a Memory.” Critical Inquiry, vol. 35, 2008, pp. 148-71.

Delagrange, Susan. Technologies of Wonder: Rhetorical Practice in a Digital World. Computers and Composition Digital Press, 2011.

Durack, Katherine. “Gender, Technology, and the History of Technical Communication.” Technical Communication Quarterly, vol. 6, no. 3, 1997, pp. 249-60.

Enoch, Jessica and Jean Bessette. “Meaningful Engagements: Feminist Historiography and the Digital Humanities.” CCC, vol. 64, no. 4, 2013, pp. 634-60.

Feminisms and Rhetorics Conference. “Past Conferences and Calls.” Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition, femrhets.cwshrc.org.

Filipacchi, Amanda. “Wikipedia’s Sexism Toward Female Novelists.” The New York Times, 24 April 2013. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/28/opinion/sunday/wikipedias-sexism-toward-female-novelists.html

---. “Sexism on Wikipedia Is Not the Work of ‘a Single Misguided Editor.’” The Atlantic, 30 April 2013. https://www.theatlantic.com/sexes/archive/2013/04/sexism-on-wikipedia-is-not-the-work-of-a-single-misguided-editor/275405/

Graban, Tarez Samra. “Exploring, Curating, and Creating: Using Digital Rhetorical Tools for Archival Work.” Engaging Networks and Ecologies, Conference on Community Writing, 20 October 2017, The University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, CO. Conference Workshop.

---. “From Location(s) to Locatability: Mapping Feminist Recovery and Archival Activity through Metadata.” College English, vol. 76, no. 2, 2013, pp. 171-93.

Jewish Women’s Archive. “Can We Talk?” The JWA Podcast. http://jwa.org/podcasts/canwetalk

Kirchner, Lauren. “When Discrimination Is Baked into Algorithms.” The Atlantic, 6 September 2016. https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2015/09/discrimination-algorithms-disparate-impact/403969/

Lepore, Jill. “The Cobweb: Can the Internet be Archived?” The New Yorker, 26 January 2015. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/01/26/cobweb

Lewis, Justin. “Participatory Archives and Technological Mediation: A RGS Approach to Understanding Tool Use in Digital Environments.” Enculturation, no. 20, 2015. http://enculturation.net/participatory-archives-and-technological-mediation

McPherson, Tara. “Why Are the Digital Humanities So White? Or Thinking the Histories of Race and Computation.” Debates in the Digital Humanities, edited by Matthew K. Gold, University of Minnesota Press, 2012, http://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/debates/text/29.

Palmer, Joy. “Archives 2.0: If We Build It, Will They Come?” Ariadne, vol. 60, 2009, http://www.ariadne.ac.uk/issue60/palmer.

Ramsey-Tobienne, Alexis. “Archiving Protest: How We Save and Remember Moments of Dissent.” Rhetorics, Rights, (R)evolutions, Feminisms and Rhetorics Conference, 4 October 2017, The University of Dayton, Dayton, OH. Conference Presentation.

Rise Up! A Digital Archive of Feminist Activism. Rise Up Feminist Archive, 2016, http://riseupfeministarchive.ca

Storify. http://storify.com.

Webrecorder. “About.” Rhizome. http://webrecorder.io/_faq.

Zacchiroli, Stefano. “Setting Up an Archive of Publicly Available Source Code Is Urgent.” Interview by Gabriela Motroc. JAX Magazine, October 26, 2016. https://jaxenter.com/archive-of-publicly-available-source-code-is-urgent-interview-129816.html

ZeeMaps. https://www.zeemaps.com.