Vani Kannan, Syracuse University

(April 20, 2016)

Introduction

Kirtan, by definition call-and-response singing of devotional songs or mantras, has a rich and multifaceted history, and is practiced within various religions, such as Hinduism, Sikhhism, and Buddhism, as well as secular popular music venues and community contexts. In the U.S., kirtan is popularly associated with Gaudiya Vaishnavism and the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), which was founded by a Hindu man named A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. After traveling to New York in the 1960s, Prabhupada quickly gathered a following that became popularly known as the Hare Krishnas. Since then, kirtan has taken off in the U.S., particularly in yoga studios.

Likened to a theatrical folk song in performance, kirtan doesn’t belong to the musician—the songs are co-constructed through call-and-response. For this reason, perhaps kirtan attracts audiences—and musicians—who are hungry for a musical experience different from the one offered by the performer/audience binary. I include myself in this camp. Although I first encountered kirtan in temple settings (where I participated as a flutist), I spent four years playing flute in a kirtan band that predominantly performed in yoga studios. In these performance contexts, I often puzzled over a question that I now see as a space of cultural rhetorical inquiry—what, exactly, was happening when our band performed bhajans—devotional Hindu songs that repeat the names of gods and goddesses over and over—in a “nondenominational,” “secular”1 space? Audience members were not simply consuming kirtan, but actively co-constructing it with their voices and bodies, as they swayed, clapped, and danced to the music.

In this article, I explore this question via one particular mantra called the mahamantra that will be familiar to any readers who have attended kirtan, been to a Vaishnav temple, or heard popular songs like George Harrison’s “My Sweet Lord”2:

Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna

Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare

Hare Rama, Hare Rama

Rama Rama Hare Hare

Inspired by the eleventh-century theologian Anantanand Ramanuja, and the sixteenth-century Bengali saint Chaitanya, Prabhupada taught his New York City followers to chant the mahamantra (or “great mantra”) daily as “one of the essential practices of discipleship”; in doing so, he “introduced a distinctive form of Hinduism to the American religious landscape” (Rambachan 393). The mahamantra is one that our kirtan band—which, except for me, consisted of Vaishnav musicians—performed at every single one of our yoga-studio concerts. When I first began playing kirtan in yoga studios, I was unsure how audiences would respond to it. However, kirtan attendees participated enthusiastically in singing it.

In the Sanskrit language, the word “mantra” refers to sacred words, phrases, or sounds; furthermore, in Vaishnavism, the mahamantra is designated “the most powerful among numerous mantras” and is considered particularly effective for invoking the presence of God (Schweig 27). As James Paul Gee argues, “Words have histories. . . . Words bring with them as potential situated meanings all the situated meanings they have picked up in history and in other settings and Discourses” (quoted in Mao & Young, 5). What histories and potential situated meanings, then, manifest when kirtan is performed in yoga studios?

As LuMing Mao and Morris Young write in Representations: Doing Asian American Rhetoric, “western” and “nonwestern” rhetorical practices meet at an “’unruly borderlands’ in want of exploration, cultivation, and conversion,” and embody “internal differences, ambivalences, and even contradictions” (4-5). I situate this investigation of kirtan at the unruly borderlands of sacred and secular rhetorics, where I dwelled for the years that I played kirtan. I draw from that experience to offer a theorization of “embodied circulation” via scholarship in music and rhetoric, then explore the history of kirtan within canonical texts of Vaishnavism, and finally overview competing “sacred” and “secular” claims to kirtan in popular media. I end by exploring the implications of the tension and slippage between the religious framing of kirtan as a practice for developing an ethos of worship, and the popular framing of kirtan as an art form that transcends religious identification—a tension that opens up questions about logics of inclusion and exclusion and the transnational politics of multiculturalism embodied in popular kirtan performance.

Embodied Circulation in Kirtan Performance

As a musician, kirtan practice and performance (and my participation in it) have significantly shaped how I imagine the possibilities of musical spaces. Because of this embodied musical memory, I have since found my way into spaces where collective music-making takes place, challenging dominant and restrictive paradigms of performance. I had experienced these dominant paradigms playing classical music and then later playing in rock music bands in contexts that were tightly tethered to hegemonic constructions of gender, musicianship, and other normative embodied performances. Then, there were the concerts I attended, with performers onstage and audience members (often spatially lower than the performers) paying money to witness the making of music. Spaces of kirtan performance, in contrast, are a site where this divide is blurred.

Audio recording. The mahamantra, recorded by the kirtan band I played with.3

The liberatory experience of playing kirtan resonates with the attention paid by scholars of cultural rhetoric to the embodied experiences and relational knowledges of our own lives (Powell, Levy, Riley-Mukavetz, Brooks-Gillies, Novotny & Fisch-Ferguson). Drawing from Walter Mignolo’s decolonial theories, the authors foreground the importance of making to cultural rhetorics, clarifying that making is cultural rhetoric, and that decolonial cultural rhetorics offer a space to de-link from dominant paradigms, situating these paradigms as one option among many. Kirtan can be understood as a site of embodied, relational, collective making: a room full of people make meaning through sound and language via call-and-response singing, offering an opportunity to de-link from the hegemonic performer/audience binary that we see frequently in spaces of classical and popular music performance.

Not surprisingly, this practice of communal call-and-response singing (termed choric rhetoric) has historically been tied to common worship and “inculcating communal values” (Rand 31-32). These values may be sacred or secular (or, as in the case of popular kirtan, somewhere in between). Writing about call-and-response folk songs, Lawrence Berger notes that the song genre provides a useful vehicle for distilling an organization’s ideologies, “simplify[ing] or concretiz[ing] their abstract ideals” and “encourag[ing] the listener to become physically and emotionally involved in the song” (69). Call-and-response songs are thus co-constructed and circulated through the bodies of both performer and audience—and the rhetorical work of these songs must be understood not solely in terms of the physical act of listening, but also in terms of active participation and collective making.

In order to move towards exploring the values and ideologies that are produced and circulated in kirtan via the mahamantra, I look to theories of embodied rhetoric as they intersect with music, paying special attention to the performance conventions of popular kirtan. Songs in kirtan are repeated over and over (sometimes for over an hour), with singer(s) calling out each line and audience members responding in turn. This type of repetition has been tied to ethos formation; for example, Debra Hawhee analyzes the use of rhythm, repetition, and response in sophistic training, where “regulated repetition” was understood to “produc[e] disposition” (147). This repetition was seen as deeply tied to music, where “bodily habits emerge from an opening up of the body for alliance formation” (150). Although Hawhee does not specifically investigate religious alliances, it stands to (sophistic) reason that repetitive musical practices can shape either a sacred or secular ethos, depending on the context.

Because mantras are sung to melodies in kirtan performance, it is important to consider not only “bodily pedagogies” of rhythm, but also the links between rhythm, rhetoric, and melody. Rhetorical perspectives on music have historically reflected a tendency to privilege language over other forms of communication. As Steven Katz writes in The Epistemic Music of Rhetoric, music positions us within a debate about “the relationship between oral and literate modes of reasoning, between phonocentric and logocentric discourse” (2). This debate has raged in classical rhetorical theory, where music was traditionally viewed as affectively powerful, and thus dangerous and anathema to rationality. In “Language’s Duality and the Rhetorical Problem of Music,” Thomas Rickert sums up the perspectives of Plato, Aristotle, and St. Augustine as follows: “[o]verwhelmingly, the intellectual tradition has considered music suspicious if not dangerous” (157). This suspicion, Rickert argues, was due in part to the undeniable power of music, which was seen as “more affectively powerful” than language, “but indeterminately so, which opens the door, it is argued, for all manner of impropriety, decadence, and ill-virtue” (157). The “indeterminate” nature of music’s affective power was seen as dangerous because it threatened rational thought; furthermore, its sonic character threatened language-centric epistemologies, where there is suspicion of the idea that “anything can be known which cannot be named” (Vickers 44). As I explore shortly, this understanding of music differs significantly from the Vedic theories of sacred meaning-making through sound that historically underlie kirtan.

Kirtan offers an important site to explore the embodied rhetorical possibilities of rhythm and melody working together on/with the body. Robert DeChaine argues that a listener’s body plays a role in constructing a musical text: “[t]he body offers itself up in collaboration with sound in the production of the musical text. In this way, it functions as both performer and instrument” (83). This suggests that even if a song is not performed through group- or call-and-response singing, listeners’ bodies are still implicated in its co-construction. In “Voice in the Cultural Soundscape: Sonic Literacy in Composition Studies,” Michelle Comstock and Mary E. Hocks echo DeChaine’s embodied understanding of music, offering further justification for centering sound in a theory of embodied rhetoric: “Indeed, because sound is composed of atoms and matter, we often hear with our whole bodies.” As Byron Hawk and Thomas Rickert write in the introduction to the special issue of enculturation on music, “to confront music is to address the issue of being composed.” Listeners’ bodies are conscripted into song texts in a way that differs from alphabetic texts that do not engage with sound.

When words are added to the equation, combined with melody and rhythm, the rhetorical possibilities extend even further. Deanna Sellnow argues that songs have the power to “simultaneously reinforce an ideology for members while attempting incrementally to recruit nonmembers” (72). This idea of simultaneous reinforcement and recruitment, and using music as a medium to communicate a message that audiences might be resistant to, has particular significance when considering melodic arrangements of the mahamantra, which—as I explore in the next two sections—are bound up in rhetorics of both secularism and the sacred. These two contextual frameworks—sacred and secular, and the slippage between them—affect any interpretation of the meaning-making that takes place in sites of kirtan performance when mantras like the mahamantra are sung in call-and-response.

Kirtan, Vaishnavism & Sacred Sound

The repetition of the mahamantra, a practice popularized by Prabhupada and deeply engrained into daily Vaishnav practices of worship, is closely tied to the formation of a particular Vaishnav ethos. Vaishnavism came to the U.S. in 1966, when A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada moved from India to New York City and founded the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON).4 The word Vaishnavism is derived from Vishnu, the god of sustenance, worshipped in the form of his avatars5 Rama and Krishna.6

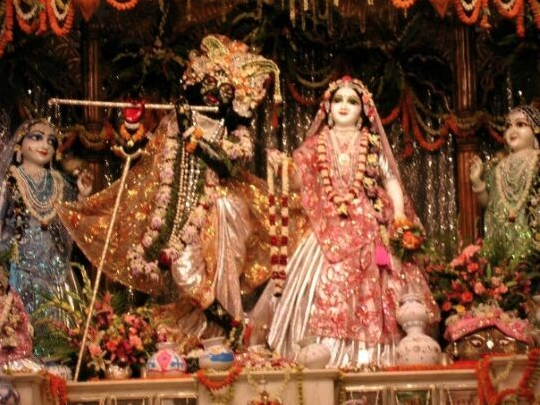

Figure 1. Shrine to Krishna and Rama, with Krishna playing the flute.7 In the bhakti tradition, the flute symbolizes “appreciation for God’s beauty”; Krishna is often depicted (in statues and in Sanskrit verse) playing the flute: “This is a distinguishing feature of bhakti: the enchanting beauty of God ever drawing souls back to him, by means of his divine flute playing” (Schweig 24).

Kirtan, as a musical ritual, supports the Vaishnav ethos bhakti—or devotion to a personal deity as the means of worship (Prentiss 3). While bhakti is contextually-specific in terms of how it is materially realized as a practice of worship, there is some consensus that it was first articulated as an autonomous religious path and “method of religious experience that leads to liberation” (Prentiss 4) during the 7-13th century Bhakti movement in India. In the Bhagavad Gita, the core text of Vaishnavism,8 bhakti is “put forward as the crux of man’s religious quest for union with God and of its desired union with karma (action) and jnana (knowledge)” (Singh 75). In Vaishnavism, kirtan—along with food rituals9—is a key way in which bhakti is practiced. Specifically, chanting the names of Krishna and Rama in kirtan serves as a way of expressing the desire for “theistic intimacy,” or the erotic, loving relationship between worshipper and worshipped10 (Bennett 194; Schweig 14).11 The practice of chanting kirtan, then, is deeply entwined with an ethos of worship, and there is an implicit question about whether it can be un-entwined from this history, depending on the “secularism” of the space in which it is being performed. Furthermore, as Karen Prentiss argues in The Embodiment of Bhakti, the personal, intimate devotion to god must be understood in terms of embodied practices like chanting—in other words, in terms of an embodied ethos.

The mahamantra’s connections to the sacred run deep, not only in terms of Vaishnav religious practice, but also in theories of sound itself. In Sonic Theology: Hinduism and Sacred Sound, Guy Beck draws deep links between sound and worship in Vaishnavism, arguing that “sacred sound in Vais[h]navism12 conforms to the basic patterns of Hindu theism . . . sacred sound constitutes a central feature of Vaisnava theology and practice” (203). Beck notes that initiation into the Vaishnav tradition involves whispering the mahamantra and that “the loud singing of God’s name(s) was more effective in the requisition of salvation, since the loud exclamation (sankirtana) of God’s name is more expressive and thus conducive of the kind of Bhakti sentiments required for the highest spiritual experience, namely, love of God” (200, 201). Kirtan—derivative of sankirtana—is a primary means by which the names are loudly chanted.13

The repetition of names in the mahamantra is understood as a physical practice of worship that brings the Vaishnav singer closer to the transcendent presence of God—in other words, as a way of embodying and circulating (via performance) a Vaishnav ethos. Beck contextualizes this specific reading of Vaishnav music within the larger Hindu concept of nada brahman, the idea that all beings (and the universe) are composed of vibrations—a philosophy that centers sound in both ontology and in practices of worship. Within Vedic philosophy,14 the repetition of Sanskrit mantras is understood to have profound vibrational effects on the body, mind, and spirit; the language itself is deeply connected to the ethos of bhakti.

These deep links between Hinduism and “sacred sound” are significant when considering the rhetorical implications of singing the mahamantra within a “secular” space like a yoga studio in the U.S., where more often than not participants are not familiar with the Sanskrit language and cannot translate the mantras they are chanting. There is a deep rhetorical question here about the degree to which this comprehension matters—and the function of multicultural rhetorics of spirituality that claim it doesn’t matter. These rhetorics of multicultural spirituality are made visible in the next section, where I explore the tension between framing kirtan as sacred or secular by drawing on published responses to its popularization. Exploring this sacred/secular rhetorical tension opens up deeper questions about the ethos conditioning that accompanies the embodied circulation of kirtan in yoga studios.

Spirituality, Multiculturalism & Popular Kirtan

In investigating popular media depictions of kirtan, I want to keep in mind the context of the mahamantra as a practice of bhakti, and think about how this embodied practice of worship shifts when the mahamantra and other mantras move in a context where they are framed as unaffiliated with a particular religious tradition, commodified for paying customers. Given this shift, how can we understand the meaning-making taking place in popular kirtan performances—particularly when we keep in mind the power of collective music-making as an embodied rhetorical act?

Rather than condition an ethos of bhakti, in yoga studios, the ethos seems to be one of multicultural, pluralistic spiritual transcendence. There have been several popular news articles on kirtan in recent years, and each of them situates kirtan as a blurry hybrid of sacred and secular. Out of the space between sacred and secular, two primary rhetorical tendencies emerge: rhetorics of multicultural pluralism and rhetorics of spirituality. For example, writing for the New York Times in an article entitled “Yoga Enthusiasts Hear the Call of Kirtan,”15 Sara Eckel blurs sacred and secular descriptors, describing kirtan as “a definite scene—a mix of a religious revival meeting, a Grateful Dead concert, and summer camp.” Within this hybrid designation, she also cites the bodies present, aligning yoga-studio kirtan with white cultural appropriation by remarking that in order to enjoy the experience of kirtan in a yoga studio, you must “adjust your comfort level to include white people in dreadlocks and saris.” Noting that kirtan has moved from places of worship and yoga studios into mainstream music venues, Eckel quotes the Grammy-nominated kirtan artist Krishna Das, who frames the mahamantra’s Vaishnav grounding as baggage carried by an otherwise secular practice:

Although kirtan is rooted in India’s devotional religions and involves chanting the names of God, Krishna Das says the practice requires no allegiance to any deity or set of beliefs, and he is dismayed that many associate the chant “Hare Krishna” with people who begged on the streets and danced in airports in the 1970s.

In order to secularize kirtan, Krishna Das temporally distinguishes it from the roots of Vaishnavism in the U.S., tying it instead to a secular, multicultural present. Embodied performance is an important rhetorical consideration here, too: Krishna Das is a white U.S. citizen who grew up on Long Island as Jeff Kagel and traveled to India in the 1970s. Often, when I performed kirtan in yoga studios, I was the only person in both the band and the audience who was not white—now, I suspect that the bodies that perform kirtan play an important role in this secularizing function, sanctioning kirtan for audiences that might be less uncomfortable practicing a Vaishnav ritual when it is sung by white musicians—and in the process constituting a majority-white audience for yoga-studio kirtan. While perhaps this kirtan may seem less “authentic,” it becomes more accessible.

Within this media rhetoric of multicultural pluralism, there is slippage between sacred and secular. For example, a Washington Post article echoes the descriptions of bhakti propagated by the Vaishnav movement, but translates bhakti from a specifically-Vaishnav practice into a universal need that all audiences are presumed to share: “[Kirtan] fills a need to experience the divine. In with the intense, personal God, out with the aloof, remote one” (Boorstein).16 However, even out of this explicitly sacred framing of kirtan, Michelle Boorstein shifts to a secular framing, citing the sense of community in kirtan performance, and the nondenominational target-audience of kirtan performers:

While it began as a mode of worship, for most practitioners today, going to a kirtan has nothing to do with embracing or even learning a particular theology. Most people don’t know the literal meaning of the chants. They come to be part of a powerfully emotive, spiritual, communal musical event. . . . The swath of America that has no particular religious affiliation—but that rejects “atheist” or “agnostic” labels—has stretched from 8 percent in 1990 to nearly 20 percent today. This is kirtan’s market.

With these statistics, it is hard to divorce kirtan’s increasing popularity from the slippery sacred/secular rhetorics that define it, or from its designation as a profitable commodity. Boorstein’s suggestion that kirtan’s “emotive” power is not tied to the literal meaning of the chants further distances mantras from their tie to the ethos of bhakti, shifting the focus from the words to the music and secularizing the music.

The material artifacts of religion in yoga studios where kirtan is performed—for example, photographs of Indian saints—also seem to play a role in this rhetorical process of secularization/spiritualization. Writing about these artifacts, Boorstein notes that “such details are increasingly meaningless to a more pluralistic America that sees many ways to grace and ritual and divine ecstasy.” In the yoga studios where our band played, we often saw religious iconography from various traditions associated with South Asia (e.g., statues of Krishna or Buddha), removed them from their culturally- and historically-specific contexts and recast in a rubric of multicultural pluralism. The Sanskrit mantras are similarly recast; Boorstein cites several kirtan enthusiasts who admit that they do not know the meaning of the Sanskrit chants, but still see them as having “holy” power.

Instruments also seem to play a role in secularization. In an article on kirtan in the Florida Times-Union, Heather Lovejoy notes that instruments like guitars make kirtan more accessible to a non-Hindu audience. In addition to serving as a coded-“western” instrument, the guitar transforms kirtan’s sonic quality to resonate with the ears of “western” listeners, and also serves as a “way in” to kirtan performance for musicians who do not play traditional kirtan instruments like the harmonium. As both a material object and a sound-producing artifact, the guitar brings kirtan under the rubric of secularism and multicultural pluralism. From this perspective, my metal flute (as opposed to a wooden Indian flute) likely participated in secularizing kirtan for yoga-studio audiences as a recognizably “western” instrument.

This process of recasting kirtan in a rubric of secularism, multiculturalism, and spirituality has transnational implications, as we see in the response by right-wing Hindu organizations in the U.S. For example, the Hindu America Foundation (HAF) has made claims to kirtan’s authenticity as a sacred Hindu practice. Suhag A. Shukla, managing director of the H.A.F., responded directly to Eckel’s New York Times article’s claims about kirtan’s secularism in an unpublished letter to the editor that appears on the HAF Web site. Interestingly, in order to reclaim kirtan as a collective, cultural practice with a particular geopolitical grounding in South Asia, Shukla echoes the popular media depictions of kirtan-as-“spiritual,” applying a rhetoric of multiculturalism to kirtan by translating that multiculturalism from kirtan to the Hindu religion itself:

Kirtan is an essential form of worship for over a billion Hindus worldwide with definitive Hindu roots. Kirtan is conducted at temples, in homes, during Hindu holidays and rites of passage and any occasion in between. And by the author's own description, kirtans are in Sanskrit and invoke names such as Lord Shiva and Lord Krishna, all Hindu names for God, by my count. That millions of people are finding solace in this ancient Hindu practice is truly inspirational. But, the author fails to acknowledge the fundamental reason as to why this is possible . . . kirtan is accessible to all, regardless of religion, and possible because of a brand of pluralism that is quintessentially Hindu.

However, scholarship in Asian-American cultural rhetorics and geopolitics necessitates that we interrogate both this cultural rhetoric of Hinduism, and the notion of “collectivity” that I assigned to kirtan performance at the beginning of this article. Who has historically been included in and excluded from this “collective”? Who has access to spaces of kirtan performance? For whom is kirtan performance considered acceptable? To consider these questions as they relate to rhetorics of the sacred, it is important to consider what Chakravarty terms “rhetorics of exclusion” in right-wing Hinduism in the U.S. (she includes the HAF in this category). These rhetorics of exclusion have ties to Hindutva—a political project of Hinduism that is closely tied to India’s (post)colonial history and caste politics. In “Ghosts of Yoga Past and Present,” Prachi Patankar rebuts the HAF’s claims to the Hindu authenticity of practices like kirtan and yoga, noting that the language in which kirtan is chanted—Sanskrit—has historically been framed as a “language of ‘divine knowledge’” only available to upper-caste Hindu Brahmins: “[a] founder of the bhakti movement in Maharashtra, Dnyaneshwar, was shunned by the brahmin community for trying to bring Sanskrit to the “common people.” While popular kirtan could thus be understood as a way to circulate Sanskrit among non-brahmin population, there is also a question of whether its circulation in U.S. spaces—framed in rhetorics of multicultural pluralism and secularism—actually serves to obscure these histories and present-day realities by normalizing Sanskrit Hindu mantras as secular/spiritual popular culture, and in doing so, bolstering a transnational project of Hindutva that has been recently challenged by social movements including the Dalit Women’s Self-Respect Yatra.

The politics of cultural appropriation are complex here; the imperative is not to make claims to a “pure,” Indian authenticity that is sullied by popular kirtan (the term “Indian” immediately consolidates over one billion human beings with dispersed, heterogeneous cultural practices that include kirtan). Instead, there is a deeper political question about what is sayable or unsayable, and for whom. What is the impact of the increasing popularity and marketability of kirtan and its emergent ethos of spiritual, multicultural pluralism? Because of the religious context outlined above, and the history of the bhakti tradition in the U.S., I want to argue that kirtan (both singing the mahamantra and, in my case, making noise on the flute) is laden with these transnational histories, tensions, and contradictions whether or not they are articulated in the performance space itself. By chanting mantras set to melodies, kirtan participants in yoga studios unwittingly embody, perform, and circulate these ideological contradictions. The messy question—to what end?—remains.

Theorizing from Tension

What can we learn from these competing cultural rhetorics through which meaning is made around kirtan? I never resolved the sacred-versus-secular question for myself when I was performing kirtan, and ultimately I quit kirtan because I couldn’t reach clarity around the question I began with—what, exactly, was happening when our band performed bhajans—devotional Hindu songs that repeat the names of gods and goddesses over and over—in a “nondenominational,” “secular” space? In short, I couldn’t figure out quite what I was embodying on stage as a half-Indian metal flute player who does not practice Vaishnavism (versus the often-white wooden-flute-playing kirtan musicians that populated other kirtan bands in yoga studios). Questions of authenticity, cultural appropriation, and the sacred/secular divide were with me often, set against the undeniable power of collective music-making and the embodied circulation of meaning through words and sounds.

The existence of this tension poses questions.17 These questions I end with include: How do we think about kirtan as embedded in transnational capitalist markets that seek to package and commodify cultural practices and legitimize them via rhetorics of hybridization and cosmopolitanism? What, exactly, is being sold when people pay to sing kirtan in a yoga studio? For whose benefit is it packaged and commodified? What are kirtan’s political implications as the U.S. and India’s geopolitical alignment shifts? Do its sounds, words, and artifacts in yoga studios play a role in consolidating an imagined geography of India-as-Hindu? And finally, as a movement to contest Hindutva and caste supremacy gains traction, what is the demand on those of us in the diaspora when faced with the popularization and normalization of practices like kirtan, when organizations like the HAF claim kirtan as “quintessentially Hindu”?

As I continue to tease out these constellated questions and the stories underlying them, I am left with the thought that the tension I registered while performing kirtan is a space in which cultural rhetorics can be theorized—the tension between collective making as liberatory musical practice and commodification; between authenticity and appropriation; between sacred and secular; between normalization and resistance.

- 1. I use scare-quotes when discussing “secular” yoga studios, because although yoga studios popularly market themselves as secular, many of them incorporate Hindu and Buddhist symbols and objects (such as statues of Ganesh or Buddha).

- 2. Harrison became a follower of Vaishnavism.

- 3. Courtesy of Keshavacharya Das.

- 4. Because the mahamantra grew out of this “international” organization, there are complications in framing this kirtan mantra as “Indian-American.” However, materially, I want to ground this analysis in Prabhupada’s move from India to New York, and the popularization of kirtan performance specifically in the U.S. Because yoga studios are the primary site where I engaged in kirtan performance, I root this study in that context, reflecting an ethic of cultural rhetorics study that holds that we should write from practices that we embody and participate in.

- 5. Avatars can be understood as manifestations of the God, in a different physical form.

- 6. While Rama is characterized as “a deity of loyalty and righteousness,” Krishna “shares more personal and passionately loving relationships with his worshippers” and in Vaishnavism Krishna is understood not only as an avatar, but also as adi-purusha devanta (i.e., the supreme and ultimate form of divinity) (Schweig 16-17). Vaishnavism thus recognizes multiple forms of a unitary deity (Schweig 18).

- 7. Public domain / Wikimedia Commons.

- 8. “. . . the Gita was considered one of the three foundational texts (prasthanatraya) for Hindu religious commentary by the great philosophers Sankara and Ramanuja, as well as in later Sanskrit philosophical tradition” (Prentiss 5). See Vijay Prashad’s Uncle Swami (pp. 166-67) for discussion of the potentially progressive politics of the Gita.

- 9. Vaishnav temples have historically served free food as part of the practice of bhakti.

- 10. This love is embodied in the concept of madhurya bhava, “the illicit love between Krishna and his consort Radha,” and viraha, or “love-in-separation”—an “incomplete or frustrated” love that devotees considered to be its purest form (Schweig 169).

- 11. During this time, Schweig writes, “western young men and women could be seen on the streets of major cities, dressed in traditional Indian religious garb,” chanting the mahamantra (14). This is true today—kirtan can often be seen in major cities and on college campuses, too.

- 12. “Vaishnavism” is spelled in various ways, sometimes with the “h” omitted as it is here.

- 13. During extended japa meditation sessions, an aksa-mala (rosary of 108 prayer beads) is counted out six times as the mahamantra is repeated, another layer of the bodily pedagogy of bhakti (Beck 202).

- 14. I use “Vedic,” “Hindu,” and “Vaishnav” very deliberately here—none of these theories should be collapsed into “Indian rhetorics,” as this represents just one out of many possible cultural rhetorical practices with roots in the Indian subcontinent.

- 15. It is interesting to note that Eckel (and, later in the article, Krishna Das) both connect this “warming up” to the fact that U.S. yoga enthusiasts often hear kirtan as they do asana poses in yoga class, particularly considering Hawhee’s “bodily pedagogies” and the idea that ethos is conditioned through repetitive motion.

- 16. This article makes interesting links to other religious traditions that engage in call-and-resposne singing, such as Catholicism, Buddhism, Islam, and Judaism. She quotes Rabbi Gil Steinlauf as saying that Washington’s largest synagogue is “in the process of a paradigm shift, and kirtan represents that.” He has integrated chanting into religious services as a result of the popularization of kirtan.

- 17. Thank you to Brian Pickett for this apt phrasing

My thanks to Professor Lois Agnew of Syracuse University for reading multiple drafts of this article and offering generous feedback.

Beck, Guy L. Sonic Theology: Hinduism and Sacred Sound. Columbia: U of South Carolina P, 1993. Print.

Bennett, Peter. “In Nanda Baba’s House: The Devotional Experience in Pushti Marg Temples.” In Owen M. Lynch, ed., Divine Passions: The Social Construction of Emotion in India. Berkeley: U of California P, 1990. 183-212. Print.

Berger, Lawrence M. “The Emotional and Intellectual Aspects of Protest Music.” Journal of Teaching in Social Work 20.1-2 (2000): 57-76. Print.

Boorstein, Michelle. “Kirtan’s Call-and-Response Chanting Draws a Growing Number of Washingtonians.” The Washington Post 1 Dec. 2012: n.pag. Web. 30 November 2014.

Chakravarty, Subhasree. “Learning Authenticity: Pedagogies of Hindu Nationalism in North America.” In LuMing Mao & Morris Young. Representations: Doing Asian American Rhetoric. Logan: Utah State UP, 2008. 106-126. Print.

Comstock, Michelle and Mary E. Hocks. "Sonic Literacy as Embodied Knowledge." In Voice in the Cultural Soundscape: Sonic Literacy in Composition Studies. Bowling Green State University, n.d.: n.pag. Web. 24 September 2013.

DeChaine, D. Robert. “Affect and Embodied Understanding in Musical Experience.” Text and Performance Quarterly 22.2 (2002): 79-98. Print.

Eckel, Sara. “Yoga Enthusiasts Hear the Call of Kirtan.” The New York Times 4 March 2009: n.pag. Web. 30 November 2014.

Hawhee, Debra. "Bodily Pedagogies: Rhetoric, Athletics, and the Sophists' Three Rs." College English 65.2 (2002): 142-162. Print.

Katz, Steven B. The Epistemic Music of Rhetoric: Toward the Temporal Dimension of Affect in Reader Response and Writing. Carbondale/Edwardsville: Southern Illinois UP, 1996. Print.

Lovejoy, Heather. “Devotional Call-and-Response Singing Kirtans Grow in Popularity in Jacksonville.” Florida Times-Union 15 Feb. 2011: n.pag. Web. 30 November 2014.

Rickert, Thomas & Byron Hawk. “‘Avowing the Unavowable’: On the Music of Composition.” Enculturation 2.2 (Spring 1999): n.pag. Web. 1 December 2014.

Mao, LuMing & Morris Young. Representations: Doing Asian American Rhetoric. Logan: Utah State UP, 2008. Print.

Patankar, Prachi. “Ghosts of Yoga Past and Present.” Jadaliyya 26 Feb. 2014: n.pag. Web. 29 November 2014.

Powell, Malea, Daisy Levy, Andrea Riley-Mukavetz, Marilee Brooks-Gillies, Maria Novotny & Jennifer Fisch-Ferguson. “Our Story Begins Here: Constellating Cultural Rhetorics.” Enculturation: A Journal of Rhetoric, Writing, and Culture 18 (2014): n.pag. Web. 1 December 2014.

Prashad, Vijay. Uncle Swami: South Asians in America Today. New York: New P, 2012. Print.

Prentiss, Karen Pechilis. The Embodiment of Bhakti. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1999. Print

Rambachan, Anantanand. “Global Hinduism: The Hindu Diaspora.” Contemporary Hinduism: Ritual, Culture, and Practice. Ed. Robin Rinehart. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO Inc., 2004. 381-414. Print.

Rand, Erin J. “‘What One Voice Can Do’: Civic Pedagogy and Choric Collectivity at Camp Courage.” Text and Performance Quarterly 34.1 (2014): 28-51. Print.

Rickert, Thomas. “Language’s Duality and the Rhetorical Problem of Music.” Rhetorical Agendas: Political, Ethical, Spiritual. Ed. Patricia Bizzell. New York: Routledge, 157-63. 2005. Print.

Schweig, Graham M. “Krishna: The Intimate Deity.” The Hare Krishna Movement: The Postcharismatic Fate of a Religious Transplant. Eds. Edwin Francis Bryant & Maria Eckstrand. New York: Columbia UP, 2004. 13-30. Print.

Sellnow, Deanna D. “Music as Persuasion: Refuting Hegemonic Masculinity in ‘He Thinks He’ll Keep Her.’” Women’s Studies in Communication 22.1 (1999): 66-84. Web. 20 September 2013.

Singh, R. Raj. Bhakti and Philosophy. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2006. Print.

Shukla, Suhag A. “HAF Writes to the NY Times about Kirtan’s Hindu Roots.” Hindu America Foundation 5 March 2009: n.pag. Web. 20 August 2015.

Vickers, Brian. “Figures of rhetoric/Figures of music?” Rhetorica: A Journal of the History of Rhetoric 2.1 (Spring 1984): 1-44. Print.