Kathleen Blake Yancey, Emerita, Florida State University

(Published March 24, 2022)

On February 14, 2018, a former high school student who had been expelled from Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School (MSD) in Parkland, Florida, for “disciplinary violations,” among them fighting, profanity, and an “assault” (Miller and Gurney), returned to school. Entering MSD on that Valentine’s Day, the gunman opened fire with an AK-47, killing 17 human beings—14 students, 1 teacher, 1 coach, and 1 athletic director—and injuring another 17 others, surpassing the carnage at Columbine some 19 years earlier.

At such a moment—as shootings at schools like Columbine, Virginia Tech, and Sandy Hook demonstrate—an overwhelming, often devastating grief prevails, as it did on that Valentine’s Day. But even in the midst of such grief, even in the immediate aftermath of such an event, there is also a kairos, an opportunity and moment for ethical rhetorical action, one wherein a constellation of private grief expands toward a shared public cause. Understanding public action as a kind of grief, the Parkland Survivors[1] acted, within days of the shooting. Beginning as a hashtag circulating on social media, their movement Never Again called students to stage a national walkout while shaming politicians into action; prompted businesses, including Delta, Avis, and Symantec, to disavow the NRA; and motivated stores to suspend selling assault weapons—all actions setting the stage for a larger political effort focused on influencing the US midterm elections of 2018, then continuing and expanding through the current moment.

From their first public response to the MSD massacre, the Parkland Survivors adeptly displayed an unusual, very savvy convergence of social media, mass media, and face-to-face interaction galvanizing many, especially youth, to support gun reform legislation; register to vote; and vote. As an index to the movement’s multifaceted media identity, the web-like media reach of the Parkland Survivors is worth noting: they created and participated in social media, appeared in mass media, published their own book, and engaged one-on-one with multiple others. More specifically, their multiple forms of social media, created within two days of the massacre, included the hashtag Never Again and the Facebook page March For Our Lives; more conventionally, they also began hosting their own website, where announcements are made, T-shirts sold, photos of past events shared. In the first weeks after the massacre, they also appeared on television shows across the political spectrum, among them 60 Minutes; the Today Show; Good Morning America; CBS This Morning; and Fox News. By October, a mere eight months after the shooting, they had published Glimmer of Hope: How Tragedy Sparked a Movement, a collective first-person account of their reactions to the shooting, their planning for what has become a movement, and their implementation of various short- and longer-terms ways to make the massacre consequential. And from the first rally, held close to home the Saturday after the massacre, through the March For Our Lives event hosted in Washington, DC, the next month, and into the summer’s multi-site Road to Change voter registration drive, the Parkland Survivors were engaged with others in very human ways. As yet another sign of their media savvy: during the Road to Change voter registration multi-city tour, they also wore their own t-shirts hosting QR codes allowing people to complete voter registration in real time.

Initiated in the shadow of the massacre, the Parkland Survivors’ activist campaign was highly unusual, their response both unexpected and selfless. Rather than focus on their own grief, the Parkland Survivors—understanding that grief in a larger context, as one (more) iteration of a continuing collective grief around victims of school shootings—acted within and according to the kairos of their rhetorical situation. Rhetorical situations, of course, are open to interpretation: a Bitzerian approach would credit the massacre with defining and permitting the occasion, while a conception more informed by Scott Consigny and Richard Vatz would assign agency for defining the situation to the Parkland Survivors themselves. Byron Hawk understands this ambiguity as inherent to kairos. Kairos, he says, oscillates between “two apparently incompatible” possibilities, one favoring the rhetor and one favoring situation. “Seizing the moment,” which Hawk allows, “means being able to anticipate it, unconsciously as well as consciously, not just reacting to it but adapting to it, with it, and often quickly” (184).

Such kairotic oscillation might also be understood as functioning through a kind of assemblage. While assemblage in Rhetoric and Composition, borrowing from Deleuze and Guattari, often describes “assembled texts, that is, texts that are composed after and with other texts” (Yancey and McElroy), it also can refer to a kind of becomingness, an emergence. As John Phillips points out in the May 2006 issue of Theory, Culture & Society, Deleuze and Guattari don’t use the word assemblage, preferring the word “agencement,” which has “the senses of either ‘arrangement,’ ‘fitting,’ or ‘fixing’” (108), much like the fittingness of kairos itself. Phillips further notes that the Deleuzian usage of agencement suggests “an event, a becoming, a compositional unity.” Bruce Braun points to a translation issue with assemblage and agencement, noting in a 2008 issue of Progress in Human Geography what he calls the “inadequate “translation of agencement to assemblage:

Deleuze and Guattari’s concept relates and combines two different ideas: the idea of ideas: the idea of a ‘layout’ or a ‘coming together’ of disparate elements, and the idea of “agency” or the capacity to produce an effect. . . . Hence, agencement neatly relates the capacity to act with the coming together of things that is a necessary and prior condition for any action to occur, including the actions of humans (671, emphasis in original).

As Yancey and McElroy observe, “Agencement thus has a connotative power that assemblage lacks in that it incorporates the notion of agency and conditions for action” (8).

The concept of agencement-assembling, in the context of the Parkland Survivors and their seizing of kairos, describes an adaptive seizing that is always emerging in accordance with a coming together of things. Each of the principal things created in response to the MSD massacre—Never Again MSD; March For Our Lives, both the March 24 march and the movement; and the Road to Change—changes as it prismatically links to other related and opposing efforts, from mental health initiatives to right-wing politics—in a continually evolving emergence. In this process and by their own account, the Parkland Survivors’ evolution has been dynamic, incremental, and emergent, moving from a rally the Saturday after the Valentine Day’s massacre to a march in Tallahassee some few days later to the March 24 March For Our Lives event to the 2018 Road to Change summer tour to Congressional Bill HR 8, still in process, and on. At each culminating moment—the March 24 event; the election of 2018; the House passage of HR 8—earlier goals have informed and been folded into new ones, all linked to gun reform, and all motivated by kairos.

The mass shooting at their high school presented the Parkland Survivors with a rhetorical situation; rhetorical situations are, however, also not discreet. Rather, as Jenny Edbauer explains, each rhetorical situation bleeds into a rhetorical ecology; a good question, one pursued here, is which rhetorical ecologies informed and interacted with the Parkland shooting, especially as the movement emerged. Additionally, as rhetorical situations are not discreet, neither are rhetorical ecologies: each rhetorical ecology can, and often does, bleed into and interact with several related rhetorical ecologies. Rhetorical ecologies linked to the Parkland Survivors’ seizing of kairos are numerous, among them

- a rhetorical ecology of mass shooting more generally

- a rhetorical ecology of gun-related US politics

- an emerging social-justice-oriented, progressive, politically active rhetorical ecology

- an antecedent rhetorical ecology with the same name, Never Again, and

- a mental health rhetorical ecology

This article also defines these rhetorical ecologies, considers how the Parkland Survivors’ agencement-emerging efforts inform and are informed by them as they continue seizing kairos, and concludes by reflecting on what the Parkland Survivors show us—about material consequences, kairos, circulation, commitment, and the research methods useful in tracing such efforts.

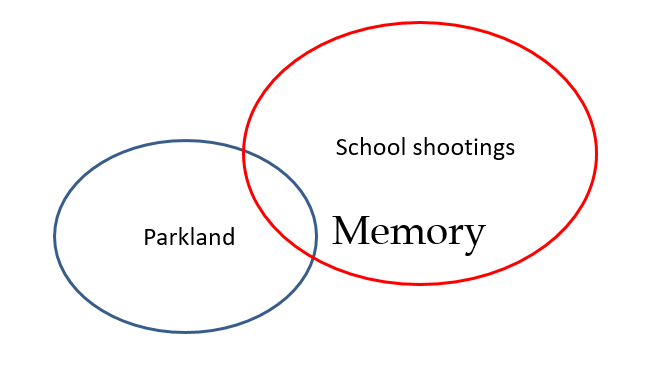

Rhetorical Ecologies

One framework for understanding the Parkland massacre is its local rhetorical situation, which is also a specific instance of a general recurring rhetorical situation, in this case school shootings in the United States. As evidenced in the hundreds of such shootings preceding Parkland, the prototypical rhetorical situation of a school shooting is exhausted by a seemingly infinite grief as parents, siblings, grandparents, classmates, and friends mourn the loss of students, teachers, coaches, and other staff, typically through funerals and other memorial activities. Each such shooting, each such rhetorical situation is unique, while each also contributes to the prototype.

A complementary way of thinking about such shootings, however, and of the Parkland shooting in particular, is through the framework of rhetorical ecologies. As Edbauer explains, rhetorical ecologies shift attention from the singular event, the local, discrete situation, to the “temporal, historical, and lived fluxes” contextualizing them, informing them, and taking them up:

Rather than primarily speaking of rhetoric through the terministic lens of conglomerated elements, I look towards a framework of affective ecologies that recontextualizes rhetorics in their temporal, historical, and lived fluxes. . . . I want to propose a revised strategy for theorizing public rhetorics (and rhetoric’s publicness) as a circulating ecology of effects, enactments, and events by shifting the lines of focus from rhetorical situation to rhetorical ecologies (9).

In other words, rather than defining an event like school shootings as a rhetorical situation in terms of its defining features—exigence, rhetor, audience, and constraints—an event-as-rhetorical situation can be conceptualized as an “emerg[ing]” rhetoric “already infected by the viral intensities that are circulating in the social field. Moreover, this same rhetoric will go on to evolve in aparallel ways: between two ‘species’ that have absolutely nothing to do with each other. What is shared between them is not the situation, but certain contagions and energy” (13). From this perspective, any event necessarily participates in a larger ecology of rhetorical circulation; so, too, for the Parkland shooting and its survivors, most immediately in a rhetorical ecology of school shootings. But as demonstrated here, in employing activism as a form of grief and thus upending the typical rhetorical situation, the Parkland Survivors also tapped and participated in several other rhetorical ecologies, among them a rhetorical ecology of mass shootings more generally; a rhetorical ecology of gun-oriented US politics; a rhetorical ecology of social-justice-oriented, progressive activism; a rhetorical ecology of antecedent efforts identically named as Never Again; and a rhetorical ecology of mental health.

The Rhetorical Ecology of School Shootings

As teenagers who have grown up in the US, the Parkland Survivors understand the rhetorical ecology of school shootings generationally. For them and for others of their generation, the shootings at Columbine and Sandy Hook provide a national context for school shootings, a point of departure for any analysis and understanding. Because of the ecology of school shootings, the Parkland Survivors thought in those terms—in the terms of earlier shootings—as they sought to make sense of their own event, of their reaction to it, and of what they wanted to occur as a consequence of it. Speaking to the role the mass media play in this ecology, for example, Parkland Survivor Delaney Tarr observed that “The way the media covers gun violence is not necessarily productive—they’re looking for the sobbing victims” (qtd. in Mahdawi), a victimhood the Parkland Survivors rejected. More pointedly, Parkland Survivor Jaclyn Corin;drew on media coverage of both Columbine and Sandy Hook to identify what was possible in such a moment, defined as the opposite of the conventional and thus as a source of kairotic invention: “No! You’re not going to cover Parkland the way you covered Columbine twenty years ago, or how you covered Sandy Hook six years ago. Something is going to change because of this moment” (qtd. in Mahdawi).

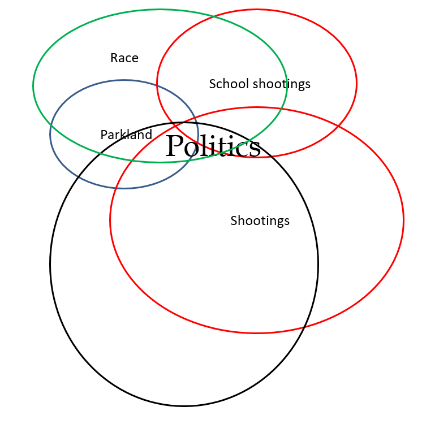

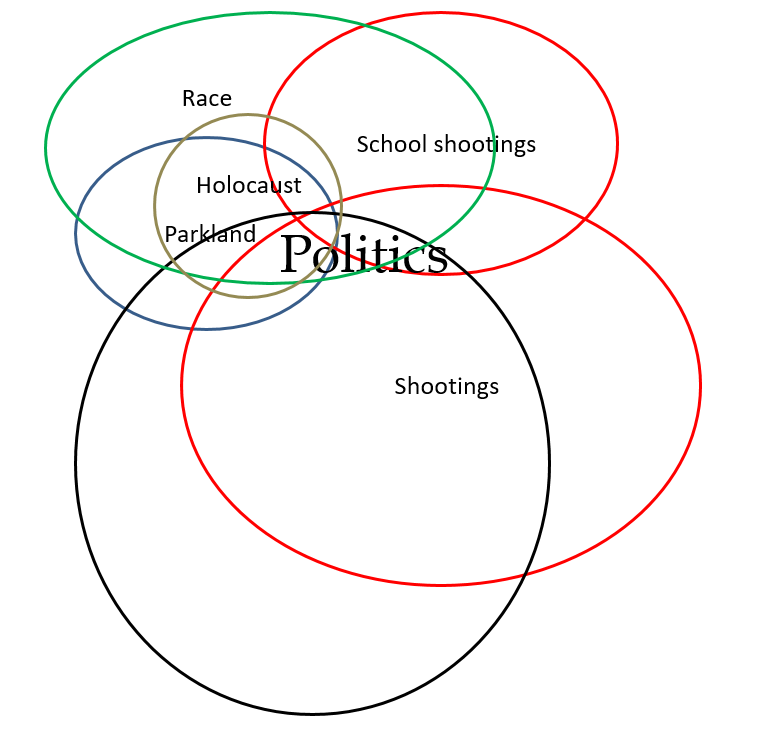

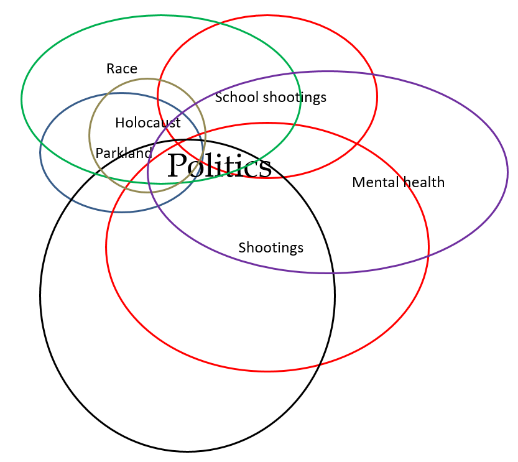

Figure 1: The rhetorical ecology of the Parkland shootings plotted as a Venn diagram with the larger rhetorical ecology of (general) school shootings, with memory as a unifying element across them.

In February 2018, Parkland was the latest instance within the rhetorical ecology of school shootings, an ecology already inhabited by numerous other school shootings like that at Newtown, Connecticut. Prior to the Parkland shooting, some students in Newtown were participating in local Parkland-like activism centered on gun regulation, keying on registering young people to vote. Jenny Wadhwa, for instance, who was a 6th grade student in a neighboring school in Newtown when Sandy Hook occurred, belongs to the Junior Newtown Action Alliance, created in the aftermath of Sandy Hook. “We’re working,” she says, “so kids like me, who are still too young [to vote] can automatically get a voter registration form on their 17th birthday.” The Alliance also raises awareness of the Sandy Hook massacre; like their Parkland colleagues, they employ digital and social media. “One committee,” Wadhwa explains, “is filming videos of students recounting their Sandy Hook stories. A few friends and I are working on an Instagram page called @HumansOfNewtownCT to put a face on the impact of gun violence and show how one AR-15 affected so many more people than those who were actually struck by bullets.”

Activism in response to school shootings is thus not new: what was new in the Parkland instance is threefold: (1) the immediacy of the effort; (2) its continuing emergence as a movement; and (3) its quickness-to-scale, given lobbying efforts in Tallahassee and a national March For Our Lives rally occurring within five weeks after the massacre. Such efforts motivated and invigorated others. Prompted by the Parkland shooting and activism, some Sandy Hook survivors became activists themselves: Natalie Barden, for example, who lost her brother at Sandy Hook, became active only in response to Parkland.

After this [the Sandy Hook shooting], I never wanted to think about gun violence. I knew the importance of gun safety, and of course, never wanted my tragedy to happen to anyone else, but as a kid, all I wanted was to be normal and not constantly reminded of my loss. I left the fighting to my dad, Mark, who started Sandy Hook Promise, confident that his efforts in gun-violence prevention would create the change that was needed (Barden).

“Inspired” by the Parkland Survivors, however, Natalie saw herself in them: “I should be able to, five years later, use my voice in that way as well” (qtd. in Hussey). As she explains, Parkland served as a “reminder that what happened in Newtown is still happening, and not nearly enough has changed in the almost six years between the two tragic events. The horror that my town felt, the pain we all still feel, happened in another town, and I saw the teenagers down in Florida immediately speaking out for gun responsibility. It inspired me to do the same” (Barden). What impressed Barden, too, was the fact that “these kids are able to speak about this topic so soon after the tragedy” (Barden). But Barden also worried that the activism would culminate in the March, that people would “stop caring,” since that’s what she saw after Sandy Hook. Informed by a continuing kairos, March For Our Lives provided both culmination and prelude to (more) activism that continues today; Barden believes that through this activism “history is being made.” The rhetorical ecology of school shootings, in other words, includes all those who have been touched by them; earlier shootings contextualize more recent massacres, while later shootings and the activities of later survivors affect earlier survivors as well.

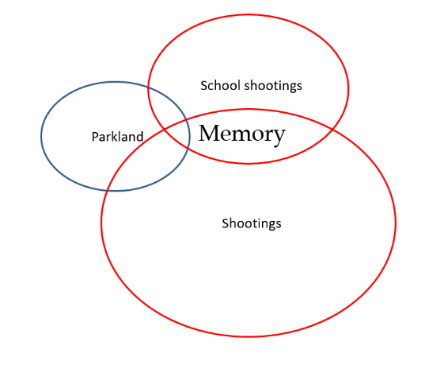

A Rhetorical Ecology of Mass Shootings, a Rhetorical Ecology of US Gun-related Politics

Figure 2: A set of Google-produced images of various mass shootings--including those at Sandy Hook Elementary, Santa Fe High School, Columbine High School, Orlando’s Pulse nightclub, and the Las Vegas Strip--as context for the shooting at Margery Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland.

Figure 3: The rhetorical ecology of the Parkland shootings plotted as a three-part Venn diagram with the larger rhetorical ecologies of school shootings and of mass shootings.

A Google search in 2019 produced an image showing a progressive chain linking mass shootings: Margery Stoneman Douglas High School to Sandy Hook Elementary to Santa Fe High School to Columbine High School to Orlando nightclub to 2017 Las Vegas Strip. Put another way, school shootings are one genre in the larger rhetorical ecology of mass shootings. Thus, when the Parkland Survivors talked about school shootings, they did so in the context—the rhetorical ecology—of mass shootings as well, which they signaled from the beginning. On February 16, 2018, two days after the massacre, their Facebook page #Never Again was launched: “Run by the survivors of the Stoneman Douglas shooting,” it announces. And then: “We are sick of the Florida lawmakers choosing money from the NRA over our safety. #NeverAgain.” In targeting the NRA, the Parkland Survivors made obvious their goal: to eliminate gun practices contributing to both school shootings and mass shootings. To do so, they widened their frame of reference to include a rhetorical ecology of US gun-related politics.

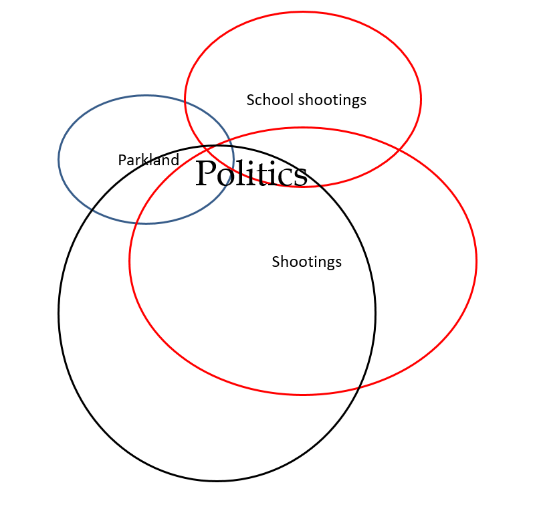

Figure 4: The rhetorical ecology of the Parkland shootings plotted as a Venn diagram with the larger rhetorical ecologies of school shootings, of mass shootings, and of politics, which informs the three shooting-related rhetorical ecologies.

The Parkland Survivors’ initial legislative goals addressed several aspects of gun practice: banning certain kinds of guns (e.g., high-capacity guns), implementing universal background checks, and funding intervention programs. Their promotions of these proposals, through rallies and voter registration drives, were likewise diverse. Guiding the activism was an emerging policy platform that thus far has taken two forms. The first platform assembled ten familiar proposals, as represented here (MFOL Katy, Texas); critical to articulating them was the language employed. As Emma Gonzalez explained, “We’re not trying to take away anybody’s guns. But they misconstrue our message, because they’re afraid of this becoming a slippery slope, or they’re afraid of us, because we have a voice now.” (Gonzalez, quoted in Cullen, Vanity Fair). Such rhetorical linguistic savvy is especially evident in the second policy platform, “A Peace Plan for a Safer America,” which replaces appeals to eliminate guns with plans for peace. As NBC news reporter Safia Samee Ali explains, the plan includes only 6 points, with each one defined and most including specific benchmarks with a twofold function: they depict a new future while providing a mechanism for calculating progress. Released by March For Our Lives in 2019 (https://games-cdn.washingtonpost.com/notes/prod/default/documents/b5f42aa7-bc54-4b3a-9de3-2c0732c6653d/note/ecfaf957-fe94-482f-82fe-e9a84da157ae.pdf#page=1), the plan’s six points include:

- CHANGE THE STANDARDS OF GUN OWNERSHIP

- HALVE THE RATE OF GUN DEATHS IN 10 YEARS

- ACCOUNTABILITY FOR THE GUN LOBBY AND INDUSTRY

- NAME A DIRECTOR OF GUN VIOLENCE PREVENTION

- GENERATE COMMUNITY-BASED SOLUTIONS

- EMPOWER THE NEXT GENERATION

The first proposal, “CHANGE THE STANDARDS OF GUN OWNERSHIP,” stipulates “a national gun buy-back program to reduce the estimated 265-393 million firearms in circulation by at least 30%” (Peace Plan, 2) which shows both how serious the current problem is and how the number of guns can be reduced. Likewise, the reduction of 30 percent identifies a goal, which provides a way of assessing progress. Likewise, the second proposal, “HALVE THE RATE OF GUN DEATHS IN 10 YEARS,” will “reduce gun injuries and deaths by 50% in 10 years, thereby saving up to 200,000 American lives” (Peace Plan, 3) Again, progress can be measured, in this case by the 50 percent reduction in gun injuries and deaths, which translates literally into saving hundreds of thousands of lives.

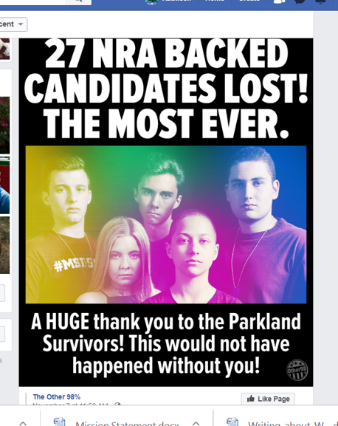

Figure 5: An image celebrating the Parkland Survivors’ role in the 2018 defeat of “27 NRA [National Rifle Association] BACKED [Congressional] CANDIDATES.”

Not least, the Parkland Survivors have translated their policy goals into specific pieces of legislation, an effort they began in earnest after the 2018 mid-term elections resulting in the Democrats re-assuming a majority in the US House of Representatives, which the Parkland Survivors have framed as a defeat of the NRA. Posted on the March For Our Lives website (https://marchforourlives.com/) in early 2019 was this announcement:

Our marching and organizing in 2018 has led us to this important point where we as a country can take another step towards ending gun violence by passing this bipartisan background check bill. We are calling on our supporters across the country to join us in the fight, and contact their elected officials to ensure H.R. 8 is passed. Together we can put an end to gun violence,

Jaclyn Corin, co-founder of March For Our Lives said.

The bipartisan background check bill, otherwise known as H.R. 8, was introduced in the House of Representatives in January 2019 and passed the next month, with most Republicans voting against it. It was sent to the Senate, where nearly three years later (as of this writing), it has yet to receive consideration. During the same time period, the House also considered and passed HR 1112, the so-called Charleston loophole bill, referring to the Charleston mass shooting in an African American church, which “would give the FBI more time to complete a background check” (Booker). Given the relationship between the rhetorical ecology of school shootings and that of mass shootings, it’s not surprising that the two bills were taken up in sequence and passed in the same week. The rhetorical ecology of school shootings has thus been legislatively linked to the rhetorical ecology of mass shootings.

Figure 6: A Gateway Pundit image promoting the idea that Parkland Survivor David Hogg was “coached” to produce “Anti-Trump Lines.”

Given the description above of these two rhetorical ecologies, one might think that they are exclusively progressive, but rhetorical ecologies are ideologically diverse and dynamic. The rhetorical ecologies hosting the Parkland Survivors included participants routinely debating and questioning the Survivors: very different arguments on what are ostensibly the same issues are a defining feature of these rhetorical ecologies. Common among the arguments hosted within these ecologies—one might even call them commonplaces—is that school shootings don’t really occur and that spokespeople emerging from them—parents in the case of Sandy Hook, for example—are so-called crisis actors hired to challenge gun rights guaranteed by the Second Amendment. So it was at Margery Stoneman Douglas High School, as reported in the New York Times: shortly after the shooting, accounts surfaced of crisis actors posing as students “who travel to the sites of shootings to instigate fury against guns” (Grynbaum). The Parkland Survivors, and David Hogg particularly, were “called F.B.I. plants, defending the bureau for its failure to catch the shooter. They have been portrayed as puppets being coached and manipulated by the Democratic Party, gun control activists, the so-called antifa movement and the left-wing billionaire George Soros” (Grynbaum). As with most conspiracies, some truth motivated this one: while David Hogg was hardly an FBI plant, his father is a retired employee of the FBI.

Figure 7: An image of Donald Trump Junior’s re-tweet of claims about the FBI seeking to undermine then-President Trump.

This rhetorical activity includes presidential politics as well, in the case of Parkland linked to President Trump, his support for gun rights, and the bogus theory that the FBI was attempting to undermine him. One of Trump’s sons re-tweeted such claims, while a right-wing website, Gateway Pundit, included posts and YouTube videos, “one of which had more than 100,000 views as of Tuesday night” (Grynbaum). Others touting such views included Alex Jones, Rush Limbaugh, and Bill O’Reilly. The Parkland Survivors were also “identified” as agents of George Soros on Gateway Pundit’s home page, whose headline announced that ‘Soros-Linked Organizers of ‘Women’s March’ Selected Anti-Trump Kids to Be Face of Parkland Tragedy” (Grynbaum). Within an hour, this claim had been shared on Facebook more than 150 times.

Figure 8: An image of Chelsea Clinton’s re-tweet inviting a Gateway Pundit reporter to “return to attacking me (or really any grownup).”

All media, but especially social media, amplify messages in rhetorical ecologies promoted by people both favoring and opposing various positions. Some of the Facebook posts regarding the alleged Soros-Parkland connection are likely merely endorsements. But other posts take an opposing perspective, even raising objections to the content posted. In responding to a tweet “claiming one student was ‘coached on anti-Trump lines’ by FBI agents,” for example, Chelsea Clinton retweeted it, inviting the Gateway Pundit reporter “to ‘return to attacking me (or really any grownup’” (Bowden). Two others, the New York Times’ Nick Confessore and MSNBC producer Kyle Griffin, also “quote-tweeted the Gateway Pundit story to denounce it” (McKew). Ironically, as Wired reports, in circulating these messages, they amplify the claim(s) they dispute. In other words, while these tweets of the Gateway Pundit story intended to support the legitimacy of the Parkland Survivors, they also necessarily shared the very claim contesting the legitimacy of the Parkland Survivors. More generally, the school shooting and mass shooting rhetorical ecologies are characterized by considerable dynamism, created in part by such circulations, in this case of multiple kinds of texts often interacting with each other: tweets, Facebook posts, YouTube videos, CNN commentary, and websites. The convergence of such multiple circulations contributes to and sustains rhetorical ecologies.

An Emerging Social-justice-oriented, Progressive, Politically Active Rhetorical Ecology

Figure 9: An update of the rhetorical ecologies Venn diagram in Figure 4 with another rhetorical ecology added: race.

Most of the Parkland Survivors—the group founding Never Again MSD, March For Our Lives, and the Road to Change—are white, but they brought to their efforts a commitment to social justice racially defined; through that commitment, they have also participated in a social-justice-oriented, progressive, politically active rhetorical ecology. Although the Parkland Survivors generated attention very quickly through social media, they understood, as Parkland Survivor Delany Tarr explained, that “the reason we’re getting this attention is because we’re privileged white kids” (Cullen 138). Moreover, the Parkland Survivors imagined their effort, originally the March For Our Lives event and then Road for Change voter registration road trip, as an iteration of a larger, longer civil rights effort, one they defined through several models of change oriented to social justice—Vietnam anti-war efforts, the 1960s civil rights movement, the California farmers’ movement, and the Freedom Riders (Cullen). Drawing on this history, the Parkland Survivors framed their own movement as one bringing people together toward common goals. As Delaney Tarr put it, “If you look at the history of other movements, all of the successful ones have been intersectional. If you look at the civil rights movement, it was people of all backgrounds, standing and fighting alongside black people. And so, March For Our Lives is about coming together as one American people.” Interestingly, their perception of this history and their role in it, as they staged marches and the summer-long voter registration drive, was projected back to them by participants in the earlier models:

We can’t begin to say how many times old people that we meet in the street have compared the March For Our Lives movement to the Civil Rights movement and the people that protested the Vietnam Wars; some of the greatest changes in our history were brought up by young Americans who were sick of not having their voices heard. Even the one and only John Lewis compared us to himself, and told us to keep stirring up “good trouble,” and Dr. Martin Luther King’s family has given us nothing but support. These are leaders whom we have learned about in school, people whom we emulate in so many ways (March For Our Lives Founders 47).

Not least, from the beginning, from a very practical perspective, the Parkland Survivors also recognized that a specific contemporary movement provided a good model as well: the Women’s March. The night of February 16th, two days after the massacre, two of the Survivors

were managing the social media … and we had hundreds of direct messages on Twitter and Facebook from people asking how they can donate and contribute, and what we were going to do next. March [F]or our Lives came out of that. It would be similar to the Women’s March. We knew we needed help and structure, so the Women’s March was kind of the model. We knew that we wanted people to be engaged—people around the country and then the world—who were reaching out (March For Our Lives Founders 18).

That was the aspiration; a contributor to its realization was Arne Duncan, former Secretary of Education and Superintendent of Chicago schools. Two weeks after the massacre and three weeks before the March 24 event, Duncan initiated a connection between students in Chicago and the Parkland Survivors. Contacting the latter though their school superintendent, Duncan linked them to Father Michael Pfleger, “the pastor of Chicago’s largest African-American Catholic congregation,” who also worked with the Peace Warriors group, a Chicago student activist group (Cullen 138-9) that he connected to the Parkland Survivors. The African-American students in Chicago wanted to meet with the Parkland Survivors in Florida, so Duncan funded plane tickets for “half a dozen kids and two parents” to fly to Florida to work with the Parkland students to plan history. By the time of the March, three weeks later, the Parkland Survivors had linked to several they included in the March who were also participating in what was developing as a unified movement:

Eleven-year-old Naomi Wadler made headlines at the March [F]or Our Lives in Washington, D.C., when she urged her audience to not forget the black girls and women who have been killed by gun violence; 17-year-old Edna Chavez represented the Latinx community in central Los Angeles in her speech; and Chicago students Alex King and D’Angelo McDade drew attention to the way communities of color suffer from gun violence in silence (Ceron).

Other efforts centered on the connection between the Parkland massacre and racial and social justice were more local and more personal, at least at first. Carlitos Rodriguez, a Parkland student, is another survivor. From Venezuela, he is also an immigrant; he knew that other Parkland survivors, especially the students of color who make up 42 percent of the school’s population, also had stories to tell and that the media, in focusing on the Parkland Survivors, wasn’t attending to these important stories. Thus, rather than let his voice — and the voices of his classmates, like Morgan Williams and Lorena Sanabria — stay silenced, the 17-year-old Junior Teamed up with classmates to mobilize, creating #StoriesUntold, a new hashtag and movement that aims to amplify the stories the media has yet to focus on, specifically by highlighting the stories of black, Latinx, Asian-American, and other minority students (Ceron).

Figure 10: An image of the Stories Untold Twitter invitation to share stories of gun violence.

Like the Parkland Survivors, #StoriesUntold sees itself as an effort supporting gun reform for all people, students lost in school shootings and adults lost in the Tree of Life Synagogue shooting alike. And while #StoriesUntold is distinct from March For Our Lives, Rodriguez sees the two working toward the same end: he applauds his now-famous classmates like Emma González and David Hogg for their efforts to make the teen-led movement more inclusive and pushing for it to feature more voices of their own black and brown peers.

Figure 11: An image of Mike Bloomburg’s Twitter endorsement of Untold Stories, asking that “we honor these stories with action.”

“We just want inclusion ― and to be able to share our stories,” Rodriguez said, noting that March For Our Lives student leaders like González are friends and support the Stories Untold project. “We’re all truly fighting for one cause,” he added. “We’re just adding more fire to this movement” (Ruiz-Grossman). Like the Parkland Survivors, #StoriesUntold has also found national attention. While Michael Bloomburg didn’t succeed in his quest for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination, he did cite #StoriesUntold in his emphasis on gun reform.

An Antecedent Rhetorical Ecology

At some level, it may be that all rhetorical ecologies have antecedents: one might argue that the antecedent for the school shooting is the set of mass shootings predating them. At the same time, some antecedent rhetorical ecologies seem historically specific, sufficiently so that they are less available for a Bakhtinian heteroglossic reanimation; and one of those antecedent rhetorical ecologies pertains to the phrase Never Again, which heretofore has referred to the Holocaust and the commitment that such an event will happen never again.

Figure 12: An update of the rhetorical ecologies Venn diagram in Figure 9 with another rhetorical ecology added: the Holocaust.

The Parkland Survivors, of course, have the hashtag with the same phrase, Never Again, created one day after the massacre. In fact, after Parkland Survivor Cameron Kasky first tweeted #Never Again, he was alerted to its tacit reference. “Wasn’t ‘never again’ a Holocaust phrase? His friends asked. Yes, but so what? They brushed it off and went with it and #Never Again was born” (Cullen 55). The Parkland hashtag Never Again, however, was quickly amended to #Never Again MSD, the letters referring to Margery Stoneman Douglas and thus locating the reference to the Parkland event. Still, the Bakhtinian use of Never Again is interesting on several counts, among them its antecedent use by the Jewish community and the reactions by different members of that community to its use by the Parkland Survivors.

As reported in a Philologos column in the Jewish periodical Mosaic, which routinely reports on Yiddish, Hebrew and Jewish words and phrases, while the phrase Never Again may have several origins, it is most commonly attributed to Meir Kahane. Founder of the Jewish Defense League in 1968, Kahane used Never Again as a slogan for the group, its message to communicate “that no longer would Jews let themselves be the victims of anyone or anything. [The phrase] ‘meant simply that Jews would fight before enduring any threat’” (Philologos). The phrase was also popularized by Kahane’s 1972 book Never Again: A Program for Survival, which described the obligation felt by those surviving the Holocaust and their descendants.

“We have seen,” he wrote there, referring to the Holocaust,

the mounds of corpses and visited the camps where they killed us. . . . By our sides were the ghosts of those who were no longer, whose blood was shed like water because Jewish blood is considered cheap. We saw their outstretched hands and looked into their burning and soul-searing eyes that peered into our very being and heard them say: Never again. Promise us. Never again. (Philologos)

Ironically, the suggestion of this Never Again is that violence, even if as a last resort, will be called upon if necessary to avert another Holocaust, while the force of #Never Again MSD is the reverse, that violence is not acceptable under any circumstances.

Some in the Jewish community have resented the Parkland Survivors’ use of Never Again, believing that its initial specific reference should be limited to it. Jackson Richman, for example, laid out the argument for this limitation in the conservative newspaper Washington Examiner:

Using “Never again” dilutes its meaning, which is typically reserved to remember those, especially the Jews like my family members, who perished in the Holocaust. Its message rose out of a greater massacre, stemming from centuries of anti-Semitism, which unfortunately continues to this day. While any murder, like what transpired in Parkland, is beyond reprehensible, history cannot be misconstrued and conflated.

Others in the Jewish community take a more ecumenical view, construing the phrase Never Again as a call for many forms of non-violence. For example, NeverAgain.com, founded in 2016, claims on its website to be “dedicated to Elie Wiesel, Simon Wiesenthal, Martin Luther King Jr. and all those who have fought for human and civil rights and fight against genocide.” It also claims the hashtag #neveragain, similar but not identical to #Never Again, and it “support[s] human and civil rights causes.” Notably, it expresses solidarity with the Parkland Survivors, claiming that “we have championed the cause of gun regulation in the U.S., and we support the efforts of the Parkland students.”

The rhetorical ecology of Never Again thus oscillates between different referential instantiations and the common theme of innocent victims lost as a consequence of injustice. In employing the hashtag Never Again, the Parkland Survivors participate in this rhetorical ecology, and in amending it with MSD, they exercise a kind of Bakhtinian connection and animation.

A Mental Health Rhetorical Ecology

For both school shootings and mass shootings, one common theory suggests that the shooters suffer from mental health issues, and they may: it’s difficult to understand the Sandy Hook shooter in any other context. Moreover, as Parkland Survivor Cameron Kasky points out in recalling his reaction to the Parkland shooting, there is a master narrative about school shooters’ mental health: “I remembered the usual narrative: Small town. Good, humble people. Some lone wolf shoots up the school. He is a misunderstood, social ostracized kid. It was a mental health thing. Somehow, mental health shot up a school” (March For Our Lives Founders 3). This narrative, however, often has a convenient political spin to it located in a binary logic: if mental health is the problem, gun reform is not the solution. Parkland Survivor Delaney Tarr, for instance, reported on a meeting with House Speaker Paul Ryan as part of a lobbying effort: “And there was a meeting with [House speaker] Paul Ryan, where we could tell we weren’t being listened to. Ryan was talking about how we need to focus solely on the mental health aspect of this, and not on gun legislation” (Mahdawi).

Figure 13: An update of the rhetorical ecologies Venn diagram in Figure 12 with another rhetorical ecology added: mental health.

In addition, the rhetorical ecology of mental health related to school shootings includes two other themes, at least: one located in an immediate chronos, one longer-term. In the immediate context, the question is whether potential shootings can be stopped before they happen. Put as a question, what actions might members of the mental health community take if they suspect that someone, especially a teenager, is planning to commit a school shooting? Psychiatrist Amy Barnhorst takes up this question by posing a scenario. Suppose that a high schooler threatens to slit the throat of a classmate; this student owns an Instagram account “where he had posted pictures of the Charleston church gunman with the word ‘hero’ underneath it, and a picture of their school captioned ‘Columbine 2.0’” (Barnhorst). In response to a call regarding the threat, the police search the student’s house, finding neither guns nor explosives. The alleged victim is too frightened to be interviewed. So: no crime, no evidence, but reasons to be concerned. In cases like these, Barnhorst suggests, a legal avenue[2] exists: the person under scrutiny can be evaluated in a mental health crisis unit.

Alas, as Barnhorst explains, such an evaluation comes with multiple caveats, which seems appropriate—healthy people should not be constrained—but which collectively preclude stopping a shooting pre-event. For one, the person being evaluated can claim that the threat was a joke. For another, as long as the person seems attentive to personal needs and basic social activity, any detention is brief, typically a few days. The scenario Barnhorst presented, however, is real, she the psychiatrist, and this scenario her conundrum. Ambivalent about the ethics of detaining someone longer-term without sufficient evidence, Barnhorst, having determined that the student “posed a danger,” invoked a “rarely used” California statute allowing her to detain him for six months so as to help him. During this time, the student developed a social network, was able to distance himself from his former social media activity, and seemed less fraught and thus less dangerous. What facilitated this change, according to Barnhorst, was linking separate domains of activity[3]: “this time we were able to close the gap between the hospital and the courts by weaving a net of support that connected them, and connected our patient” (np). While systems—legal and mental health—may not be connected, a rhetorical ecology of mental health overlaps with a rhetorical ecology of school shootings. Moreover, making material connections across rhetorical ecologies can affect the future and offer hope.

A second mental health issue related to mass shootings spans years: survivor suicides. Both school and mass shootings exert immediate effects on a widening pool—the victims who die, the victims who survive, the family members and friends of both. In response, many communities, like those surrounding Parkland, quickly take steps to help the victims. Broward County Public Schools, for example, “brought in counselors and therapy dogs for Stoneman Douglas students immediately after the shooting last year [2018]”; “at the start of the 2018-2019 school year last fall, the school district advertised the continuing operation of a ‘resiliency center’ at a park in Parkland, with counselors and support groups for families” (Mazzei). Nonetheless, a year later, within a one-week period in March 2019, two Parkland student survivors took their own lives. Moreover, the pattern of such suicides, extending beyond so-called “teen suicide clusters,” affects survivors of all ages and for long periods of time. Just after these two teenagers committed suicide, so too did Jeremy Richman, who lost his daughter Avielle in the Sandy Hook massacre seven years before. In honor of his lost child, Richman had founded the Avielle Foundation, whose purpose is to employ neuroscience research to “shed light on ‘what leads someone [like a school shooter] to engage in harmful behavior” (Smith). Richman’s dream was “a paradigm shift in the way society views the health of the brain” (Smith). In other words, although dedicated to the cause of determining what goes on in the brains of school shooters as a mechanism for prevention, Richman himself still fell victim to suicide. And he’s not alone: “Roy McClellan survived the Las Vegas shooting; within two months, he killed himself. A year after the Columbine massacre, student Greg Barnes took his life. In Chardon, Ohio, six students attempted suicide after a 2012 shooting that left three schoolmates dead. A year and a half after Columbine, the mother of a student who was severely wounded was dead by her own hand” (Scher).

A rhetorical ecology of mental health, including more than the shootings and those who die in them, thus interfaces with a rhetorical ecology of school shootings and one of mass shootings.

Kairos, Rhetorical Ecologies, and Assembling a Public

In 2004, I suggested that writers today, including student writers, were self-organizing toward various socially oriented ends and that to do so, they were drawing in novel ways on new technologies and genres. I also suggested that this development paralleled that of 19th century reading publics. Much like

19th-century readers creating their own social contexts for reading in reading circles, …[composers] self-organize into what seem to be overlapping technologically driven writing circles, what we might call a series of newly imagined communities, communities that cross borders of all kinds-nation state, class, gender, ethnicity. Composers … mobilize for health concerns, for political causes … [T]he members of the writing public have learned—in this case, to write, to think together, to organize, and to act within these forums—largely without instruction and, more to the point here, largely without our instruction (Yancey 301).

The Parkland Survivors exemplify this observation: it’s not that the Parkland Survivors haven’t learned in school—one student credited her AP class for her understanding of rhetoric—but they didn’t fully learn there what has helped them create a consequential movement:

- how to seize kairos and/to invent the movement NeverAgain/March For Our Lives;

- how to employ all available means of persuasion and share them via all media;

- how to draw on models of social justice to create their own; and

- how to participate in multiple rhetorical ecologies—those of school shootings, mass shootings, politics around guns, progressive politics, the antecedent ecology of Never Again, and mental health—as they have forwarded their cause to create collective action.

In engaging in all these activities, the Parkland Survivors have also been engaging in a kind of assemblage. Working collaboratively, the Parkland Survivors/March for Our Lives/Never Again MSD activists have been accretive, inviting new communities into that collective action, from Chicago students flown to Florida by Arne Duncan to the Congressional representatives sponsoring HR 8. As these “various entities” have assembled, the Parkland Survivors have in their thinking drawn on earlier models of collective action and on a philosophy grounded in social justice, kairotically inventing and re-inventing both themselves and an evolving consequential movement.

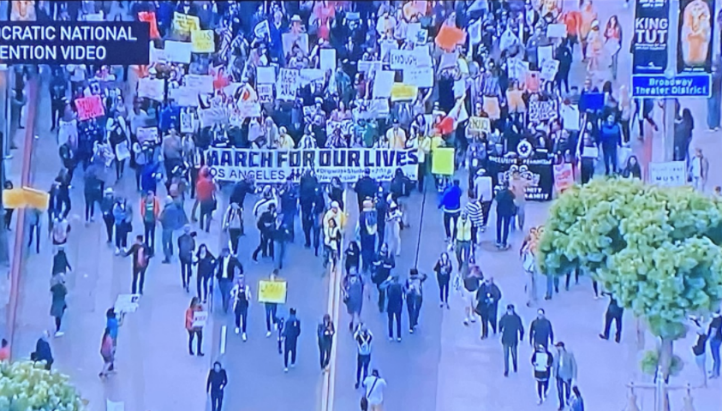

Figure 14: An image of a parade fronted with a March for Our Lives banner featured in a visual montage for the Democratic national convention.

As I completed this penultimate revision, in August 2020, another iteration of Never AgainMSD—Our Power in the States: Vote for Your Lives—was launched. In the mid-August election cycle, Never Again MSD was visually cited in a photo montage during the Democratic Convention (DNC); the week following, while the Republican National Convention (RNC) was playing out, Never Again announced This is Our Power, a voting rights initiative delivered through art/activism, in the time of the pandemic, that also included new partners, a broader set of goals, and some new conceptual framing:

With so much on the line in the 2020 election, we’re engaging young voters again (in a socially-distant, responsible way!) in nine key states where youth voters can make a real difference. We’re bringing art and activism together in a series of public art interventions and digital rallies to register, organize, and mobilize young voters ahead of the election. Each of the nine cities we’re going to will have a large-scale, on-the-ground, art intervention for local residents that will raise awareness on the systemic issues that cause gun violence — like racial injustice, immigration, healthcare, and economic inequality (just to name a few). Of course, each art intervention will be paired with voter registration, as well as digital rallies and phone banks. And we’re doing this with a coalition of inspiring partners like United We Dream, Sunrise Movement, International Indigenous Youth Council and so, so many more (Corin/MFOL, Email).

To circulate news of this effort, they relied on multiple media, including Twitter; they began their first installation in Atlanta.

Figure 15: An image of a March for Our Lives tweet invoking John Lewis’ “good trouble” in announcing the installation in Atlanta of mini-voter registration boxes with materials needed for voter registration.

What lessons might we draw from all this—kairos, Never Again MSD, intersecting rhetorical ecologies, HR 8, voter registration drives, mental health, coalitions, agencement?

One lesson, perhaps, relates to the consequential effects that young people, in this case young people ultimately from different places, can exert through rhetorical action, through organizing, reaching out, pointing to a future safer and better than the past.

Another lesson, perhaps, relates to kairos, which here, as suggested by Hawk, has oscillated between rhetorical situation and rhetors, from the specific massacre at MSD, which provided an exigence to larger, related, and intertwined social issues, traced and framed here through assemblage and rhetorical ecologies. Put another way, the Parkland Survivors’ seizing of kairos was prompted by a specific exigence in a given moment, but is not limited to it; rather, kairos has both located and accompanied an emerging and increasingly complex movement oriented initially to manifestations of problems—school shootings—but widening to address the causes of problems—which the Parkland Survivors identify as systemic issues that cause gun violence—like racial injustice, immigration, healthcare, and economic inequality—as well.

Yet another lesson relates to our understandings of circulation. As defined by Edbauer, rhetorical ecologies provide for circulations that Bitzerian rhetorical situations do not, but rhetorical ecologies also assemblage and evolve, diversifying, multiplying, interacting and overlapping, in these processes creating new intersections for invention, in this case for the invention of a movement whose goals have expanded as the movement has grown. Moreover, these circulations are facilitated by something more than convergence, by what we might think of as a convergence-plus model: with multiple genres and multiple media communicating within and across communities but toward a common goal that is always emerging.

How to trace such activity, methodologically, especially in real time, is another lesson-that-is-really-a-question. While it might not be difficult to determine the beginning point of a project like this, identifying the end is: as I write this, in May 2021, March For Our Lives is beginning a new initiative related to grant-funded community activism: shouldn’t that be included? Breadcrumbing, the process of tracking different leads online, will not necessarily lead to the Chelsea Clinton tweet, the Dave Cullen book account, or to the opinion piece by a psychiatrist. How does a researcher assure that important events and discussions are not excluded, especially given the somewhat rhyzomatic character of movements like this one? Where and how does a researcher draw boundaries? How does a researcher assure a fair treatment if she is sympathetic to the aims of the movement, if she admires the activists?

Not least, how did the Parkland Survivors have the courage to take on this effort? And as their lives have developed, how is it that they remain committed? And at what cost?

These lessons await us: in the meantime, we already have much to learn from, and be grateful for, the Parkland Survivors.

[1] Throughout this text, I refer to the students who have led the March For Our Lives movement as Parkland Survivors. Where needed for context, I have quoted or referred to them specifically. But one distinctive feature of their efforts is a collaboration located in a collective identity, which I have tried to honor here.

[2] As is no doubt clear, there are several rhetorical ecologies—like this legal rhetorical ecology—that also interface with the ones outlined here.

[3] It’s worth noting that this gap was left wide open in the case of the Virginia Tech shooter, which—had it been closed—might have helped avert that tragedy.

# Never Again. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/NeverAgainMSD.

Ali, Safia Samee. “March For Our Lives Unveils Bold New Proposal for Gun Control

Legislation.” NBC. August 21, 2019, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/march-our-lives-unveils-bold-new-proposal-gun-control-legislation-n1044996.

Barden, Natalie. “Natalie Barden Reflects on the Sandy Hook Shooting, the March for Our Lives, and Why She Still Fights for Gun-Violence Prevention.” TeenVogue, 15 Aug. 2018, www.teenvogue.com/story/natalie-barden-sandy-hook-march-for-our-lives-gun-violence-op-ed.

Barnhorst, Amy. “A New Model to Stop the Next School Shooting.” New York Times, 13 Feb. 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/02/13/opinion/school-shootings-mental-health.html.

Bitzer, Lloyd F. “The Rhetorical Situation.” Philosophy and Rhetoric, vol. 1, no.1, Jan. 1968, pp. 1-14.

Booker, Brakkton. “House Passes Sweeping Gun Bill.” NPR, 27 Feb. 2019, www.npr.org/2019/02/27/698512397/house-passes-most-significant-gun-bill-in-2-decades.

Bowden, John. “Chelsea Clinton Calls Out Far-Right Website on School Shooting Survivors: Attack Me Instead.” The Hill, 20 Feb. 2018, thehill.com/blogs/blog-briefing-room/news/374663-chelsea-clinton-calls-out-conservative-website-attacking-school.

Braun, Bruce. “Environmental Issues: Inventive Life.” Progress in Human Geography, vol. 32, no. 5, 2008, pp. 667-79.

Consigny, Scott. “Rhetoric and Its Situations.” Philosophy and Rhetoric, vol. 7, no. 3, Summer 1974, pp. 175-86.

Ceron, Ella. “Parkland Survivor Carlos Rodriguez on Using #StoriesUntold to Amplify Minority Voices.” Teen Vogue, 5 Apr. 2018, www.teenvogue.com/story/parkland-survivor-carlos-rodriguez-stories-untold-minority-voices.

Corin, Jaclyn/ March For Our Lives. “Coming to a City near you ….” August 25, 2020. Email.

Cullen, Dave. “Meet the Ultra-Organized Teenager Masterminding Parkland’s Midterms Push. Vanity Fair. October 2018, https://www.vanityfair.com/style/2018/09/parkland-gun-laws-march-for-our-lives-jaclyn-corin.

Cullen, Dave. Parkland. Harper Collins, 2019.

Edbauer, Jenny. “Unframing Models of Public Distribution: From Rhetorical Situation to Rhetorical Ecologies.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 35, no. 4, 2005, pp. 5-24.

Grynbaum, Michael M. “Right-Wing Media Uses Parkland Shooting as Conspiracy Fodder.” New York Times, 20 Feb. 2018, www.nytimes.com/2018/02/20/business/media/parkland-shooting-media-conspiracy.html.

Hawk, Byron. A Counter-History of Composition: Toward Methodologies of Complexity. U of Pittsburgh P, 2007.

Hussey, Kristen. “Emboldened by Parkland, Newtown Students Find Their Voice.” New York Times, 26 Aug. 2018, www.nytimes.com/2018/08/26/nyregion/newtown-students-activism-parkland.html.

Mahdawi, Arwa. “‘We Took Our Anger and Channelled It’: Parkland Students Jaclyn Corin and Delaney Tarr on Becoming Activists.” The Guardian, 22 Dec. 2018, www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2018/dec/22/people-of-2018-parkland-shooting-survivors-march-for-our-lives.

Mazzei, Patricia. “After 2 Apparent Student Suicides, Parkland Grieves Again.” New York Times. March 24, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/24/us/parkland-suicide-marjory-stoneman-douglas.html.

March For Our Lives. A Peace Plan for a Safer America. https://games-dn.washingtonpost.com/notes/prod/default/documents/b5f42aa7-bc54-4b3a-9de3-2c0732c6653d/note/ecfaf957-fe94-482f-82fe-e9a84da157ae.pdf#page=1.

The March for Our Lives Founders. Glimmer of Hope: How Tragedy Sparked a Movement. Penguin, 2018.

McKew, Molly. “How Liberals Amped Up a Parkland Shooting Conspiracy Theory.” Wired, 27 Feb. 2018, www.wired.com/story/how-liberals-amped-up-a-parkland-shooting-conspiracy-theory/.

MFOL Katy, Texas, https://mfolkaty.site/what-we-do.html.

Miller, Carol Marbin and Kyra Gurney. “Parkland Shooter Always in Trouble, Never Expelled.

Could School System Have Done More?” Miami Herald, 20 Feb. 2018, www.miamiherald.com/news/local/article201216104.html.

Phillips, John. “Agencement/Assemblage.” Theory, Culture & Society, vol. 23, no. 2-3, 2006, pp. 108-09.

Philologos. “What is the Source of the Phrase ‘Never Again’?” Mosaic, June 21, 2017, https://mosaicmagazine.com/observation/history-ideas/2017/06/what-is-the-source-of-the-phrase-never-again/.

Richman, Jackson. “Dear Parkland Students, Please Stop Saying ‘Never Again.’” The Washington Examiner, 7 Mar. 2018, www.washingtonexaminer.com/red-alert-politics/florida-shooting-stop-saying-never-again.

Ruiz-Grossman, Sarah. “Black and Brown Parkland Students Want You to Hear Their ‘Stories Untold’.” Huffington Post, 6 Apr. 2018, www.huffpost.com/entry/students-parkland-stories-untold-gun-violence_n_5ac7cfaee4b0337ad1e80223.

Scher, Avichai. “From Parkland to Sandy Hook, Trauma of School Shootings Haunts Survivors for Decades.” Daily Beast, 26 Mar. 2019, www.thedailybeast.com/from-parkland-to-sandy-hook-trauma-of-school-shootings-haunts-survivors-for-decades.

Smith, Tovia. “Father of Sandy Hook Shooting Victim Dies by Apparent Suicide.” NPR, 25 Mar. 2019, www.npr.org/2019/03/25/706602331/father-of-sandy-hook-shooting-victim-dies-by-apparent-suicide.

Vatz, Richard E. “The Myth of the Rhetorical Situation.” Philosophy and Rhetoric, vol. 6, no. 3, Summer 1973, pp.154-61.

Wadhwa, Jenny. “I’m a Teen from Newtown Who’s Fighting for Gun Control.” VICE, 20 Apr. 2018, www.vice.com/en_us/article/wj7ypy/sandy-hook-shooting-teen-newtown-gun-control.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. “Made Not Only in Words: Composition in a New Key.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 56, no. 2, 2004, pp. 297-328.

—-, and Stephen McElroy. “Assembling Composition: An Introduction.” Assembling Composition, edited by Kathleen Blake Yancey and Stephen McElroy, NCTE/CCCC, 2017, pp. 3-26.