E. Cram, University of Iowa

Melanie Loehwing, Mississippi State University

John Louis Lucaites, Indiana University

(Published November 22, 2016)

Contemporary protests—exemplified by the Arab Spring Movement, Occupy Wall Street encampments, pro-democracy movements in Hong Kong, and civil rights demonstrations in Ferguson, Missouri—produce an extraordinary number of digital photographs, captured by professional photojournalists, activists, everyday citizens, and police surveillance. In turn, networked spectators encounter images of protest that circulate well beyond the locales in which they are produced, becoming part of a global public discourse that generates worldwide linkages between specific protest tactics, performances of dissent, and confrontations with authority.

With the emergence of each protest and related movements, public attention may be momentarily occupied by the exigencies that mobilize bodies in politicized terrains: interstate freeways, crowded sidewalks and roadways overshadowed by smooth giants of financial capital, the everyday spaces of neighborhood streets, and so on. Importantly, as spectators link these protests and movements via similar gestures and tactics, public attention shifts toward a broader discourse about the role of social media and digital technologies in coordinating, mediating, and circulating performances of dissent. So, for example, shortly after protests in Ferguson, Missouri, intensified in response to the charge that a police officer murdered an unarmed black teenager named Michael Brown in August 2014, news commentator Max Fisher pushed the headline, “Hong Kong’s protestors are using the same ‘hands up, don’t shoot’ gesture used in Ferguson.” Accompanied by both amateur and photojournalistic images circulating on Twitter, Fisher called attention to the repetition of a gesture with transnational circulation.

Of course, it is impossible to know the intentions of the protestors; the repetition of recognizable gestures and poses from earlier protests may or may not have been deliberately used to echo the demonstrations in Ferguson. Yet Twitter participants nonetheless claimed, “Will you please show this to #MikeBrown’s parents & let them know that he changed the world? #HongKong” and “These images from Hong Kong with young protestors being gassed, with their hands up, just like Ferguson, are AMAZING” (@peaceful_birdie and @shaunking qtd. in Fisher). As these examples suggest, some public audiences recognized key visual conventions and interpreted them as an important symbolic continuity between discrete protests unfolding around the world and on their screens. It is precisely this phenomenon—the heuristic power of such recurring visual conventions of contemporary digital protest photography—to which we turn attention in this essay.

The continuity of specific visual conventions also worried public audiences, suggesting to some that subsequent protests might inherit both the gestures resonating with a global audience and the shortcomings of Occupy Wall Street (OWS) as a movement producing tangible political outcomes. Alongside protests in Ferguson, news commentators contemplated the possibilities of “the Occupy Wall Street effect,” noting similar tactics in each movement (Madhani and Alcindor). While some argued that Ferguson offered a potent corrective of historically constituted, racialized injustice to OWS’s present-oriented economic justice, others highlighted the lessons OWS offered for organizing on the ground (Madhani and Alcindor; Griffin). Further reflecting on the failure of OWS to generate enduring structural transformation, The Root’s Theodore R. Johnson argued that the movement “put the nation on notice that egregious income inequality was an injustice and unacceptable. Yet it fizzled out because it was unfocused and disorganized and lacked leadership.”

Such criticisms are not new. Since its inception, the OWS movement has been widely dismissed for its lack of efficacy. The inability to function as a traditional social movement and achieve quantifiable political objectives has been attributed to the movement’s chaotic and anti-hierarchical nature, as well as its resistance to articulating a specific political platform (Bellafante; Kristof; Feffer; Glantz; Sorkin). The analysis we offer here challenges the dismissal of OWS as “a failed movement that made no difference” (Hanno Phaenicia, qtd. in “Letters: Advice”). While it may be true that OWS participants failed as effective speaking citizens, as seeing citizens they circulated photographic conventions that offer an opportunity for a public audience to understand spectatorship, and the public’s relationship to photographs that circulate within their common culture, in newly emancipatory ways (Green).

To be clear, we are not suggesting that this rehabilitated spectatorship was a conscious aim of the OWS movement, nor are we crediting OWS as first or sole creator of the visual conventions that appear repeatedly in their photographs. Instead, we examine their production and circulation of digital protest images and read them as an inventive rhetorical practice that is both shaped by the digital technologies at hand and indicative of an emerging civic potential for spectatorship. Evaluated by traditional metrics of instrumental change, OWS protests may have produced little, but our analysis suggests that we can engage the OWS images to articulate a mode of civic pedagogy that invites a reorientation of citizens’ visual habits.[2] Moreover, engagement of digitally networked devices and platforms to remediate and circulate modes of protest rhetoric makes the study of OWS particularly important to those who seek to understand how digital technologies are altering the ways in which rhetoric is practiced and experienced by democratic citizens.

The overlapping omnipresence of such social media and digital technologies generates comparisons between media tactics of mobilizing and citizen journalism. But more important for us, these comparisons are organized by tropes—“post-occupy” and “occupy-like”—that generate a sense of public time constituted by practices of publicity organized by public screens and digital technologies. We believe that such tropic comparisons are significant indices of a broader phenomenon of digital circulation, whether or not they accurately correspond to the intentions of protestors organizing on the ground. The citation of OWS to interpret Ferguson or actions in Hong Kong becomes evidence of the circulation and transformative potential of protest photography to develop critical pedagogies of spectatorship. Our account builds on the notion of “photography” as a set of civic relations brought together in the event of photography, and in this sense, we are focused less on the technology per se and more on the ways in which it is implicated in a network of relations between photographer, spectator, depicted subjects, photograph, and camera.[2] In this essay, we take the usage of “post-occupy” as an opportunity to outline the conceptual territory needed to understand these citational practices as exemplary of a digital visual rhetoric of photography. We begin by describing protest photography in a digital media context, highlighting how the appropriation of digital technologies by protestors attends to a digital rhetoric of visuality on the basis of civic practice. Next, we situate three keywords for a digital visual rhetoric of public discourse—indexicality, circulation, and repetition—relative to photographs taken and digitally circulated by OWS protestors. Finally, reflecting on this digital rhetoric praxis, we suggest how pedagogies of spectatorship emerge through photographic practice, blurring the boundaries between author and audience, agent and spectator.

Protest Photography in a Digital Media Context

Studies of digital rhetoric have defined their object of inquiry in various ways: by focusing on technological innovation in computing that leads to revised rhetorical practice (Lanham); by repurposing classical rhetorical terminology to make sense of contemporary messages in the digital environment (Welch); and by investigating emerging rhetorical structures apparent in institutional, public, and private digital discourse (Losh). Our contribution to this conversation does not insist on a new definition for digital rhetoric so much as it suggests cultivating a more intentional connection with rhetoric’s uniquely civic traditions. We examine OWS in this essay precisely because it links rhetoric’s longstanding civic capacities with newly emerging inventional opportunities made possible by virtue of digital innovations. Of particular interest in this context is the remediation of protest photography and conventions of civic spectatorship from analog to digital cultures of production, use, and circulation.

The visibility of contemporary protest such as #BlackLivesMatter, Occupy Central in Hong Kong, Occupy Wall Street in the United States, and the 2011 Arab Spring has intensified scholarly attention to the ways in which digital technologies become operative within the life of a movement. Popular discourses of social media praise platform participation as evidence of a revolutionary and populist potential, while others caution that protest mobilized by social media generates little structural change in contrast to “traditional” protest tactics (Gladwell). In turn, recent critics of social protest move away from a tendency to privilege technological contexts as the primary force mobilizing contemporary political dissent.

In response to the habit of bifurcating online and offline worlds of political mobilization and protest, Rasmus Kleis Nielson argues that movements such as Occupy should be described as “internet-assisted,” and what others have called “digitally enabled” or “digitally networked” (174).[3] Prompted in response to arguments that digital protest relies on weak ties and the temporality and magnitude of effects, Nielson disrupts a tendency to treat digital protest as an instrumental action in which a “tool determines action,” lending focus to what digital technologies afford in the contexts of protests by examining their appropriation by activists (174).

In generating more nuanced media cultures, others have advocated for the shift from platform to ecology. Zeynep Tufekci and Christopher Wilson argue that despite the popularization of the “Twitter Revolution” in North Africa and the Middle East, “the connectivity infrastructure should be analyzed as a complex ecology rather than in terms of any specific platform or device” (365). Tufekci and Wilson describe the emergence of a new public sphere operative by the interrelations between satellite television, the Internet and dedicated social media sites, and mobile phones with picture and video capacities. In contrast, Sasha Costanza-Chock decenters analysis of particular platforms with the concept “social movement media cultures,” attentive to how social movements generate their own media infrastructures using processes of transmedia mobilization inclusive of digital and “low-tech” forms of media (378). Finally, Jack Bratich argues that the circulation of OWS memes typifies how media ecologies “facilitate the passage from information to action” (66).

But we are only beginning to understand the implications of these practices in the long view of the historical transformations of the public sphere. In order make sense of these changes, we recognize the importance of maintaining a tension between “digital media practices” and the technological, political, cultural, and social contexts in which they are situated. This is a productive tension that draws attention to the possibilities afforded by digital technology, as well as the continuities and differences of these practices relative to residual media formations; more importantly, however, it underscores an emergent transformation of participation in civic life.

Scholars maintain this tension in their analysis of OWS and similar movements, locating the dynamic media infrastructures that constituted participatory networks, including digital visual technologies such as live-stream video and memes. Despite the popular narrative that OWS failed to transform public discourse through verbal strategies of protest, media critics have focused attention on the presence of camera technologies, both analog and digital, that permeated the movement. News commenter Joshua Holland noted that protesters capitalized on the resources of livestreams to garner attention beyond Manhattan, and that digital cameras and smart phones enlivened public attention to the protesters with the viral circulation of memorable photographs such as “Pepper Spray Cop” or the masculinized bodies of Marines and Iraqi vets made vulnerable by civilian police action. Separately, Holland and Miguel Macias noted that use of screen technologies by protesters produced image narratives that countered perceptions of the movement by mainstream media, and functioned as forms of documentation that would hold police accountable. Macias, working from the popular sentiment that OWS was “the most over-documented movement in history,” asked protester-photographers, “Why do you feel the need to be shooting pictures when there are so many pictures available of the exact same thing?” Even as amateur photographers felt compelled to photograph scenes and bodies to represent their sentiments toward the movement, photographs uploaded to sites such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and Flickr bear the traces of a compulsion to repeat common visual conventions ad nauseam. Indeed, Macias’s question, alongside an expansive archive of digital snapshots, illustrates a sense of commonly shared conventions relative to recent protest photography; what is remarkable is that no one has as yet considered what those conventions are or what implications they might have as digital rhetorics and for photographic cultures of dissent.

We have been tracking and archiving OWS photographs produced since 2011, attending in particular to those images uploaded by amateur photographers on social media sites and personal blogs. In the process we have discovered an extensive, emergent online archive. Across social media sites in particular, members of the public—both those participating and those encountering the protests—have contributed a vast collection of images documenting OWS actions in cities across the United States, organized by hashtags such as #occupy, #ows, and #occupywallstreet. Unlike more intentionally curated archives, the body of work produced by the public has no central organizing system restricting use to a single site or platform, no aesthetic or professional criteria limiting inclusion in the collection, and no collaborative agreement uniting the efforts of the various skilled and amateur photographers offering up their images for public consideration. Instead, and by virtue of the social media platforms on which the images circulate, the digital collection of vernacular OWS photography resembles the unwieldy and fragmented conversations unfolding among publics where no one authority referees participation and where audiences may be constituted as publics by rhetorical address.[4]

We could impose an empirically oriented governing structure on this vernacular photographic archive for ease of study, coding and cataloguing the appearance of particular gestures or visual motifs across the images we encounter. In that case we might be able to make a plausible argument about the real-world effects of the photographs on viewers or perhaps speculate on the likely intentions that drive the repetitious use of the key visual conventions we engage in this essay. However, our aim is different: instead of making empirically verifiable claims about effects or intentions, we engage OWS photographs and the ubiquity of the particular conventions that depict camera technology within the frame as an occasion to reflect on the potential civic implications of digital protest photography. We identified these conventions for analysis as we navigated the evolving collection of vernacular OWS photography online by examining popular social media platforms (e.g., Flickr, Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, and Wordpress blogs) and searching for images tagged as being associated with OWS. In our analysis of OWS images, we approach the question of how these visual conventions implicate civic spectatorship by interrogating the remediation of civic spectatorship in digital photographic practices. Before embarking on that analysis, we first discuss the pertinent differences between analog and digital photography.

Distinguishing Digital Photography

Preliminary reflections on what makes digital images distinct from their analog predecessors focus on developing conventions of aesthetic cultures and their rhetorical entailments. Collin Gifford Brooke shifts criticism of “texts” to the media ecology of “interfaces” in which rhetoric and technology meet (6). An emergent theory of digital rhetoric depends on a dialectical approach to new media. Brooke claims that remediating the canons in digital contexts enables understanding of the rhetorical potential for new media practices, but he cautions against merely transporting hermeneutical strategies in application to digital contexts (7). Rather, just as the canons transform new media practices, new media practices transform the canons and rhetorical theory more broadly. In the context of video games, Brooke suggests that style is generative of perspective, in which interactions with interfaces “redescribe our perspectives” and suggest a position of “looking from” (140). Further attention to visual digital culture emphasizes the aesthetic conventions of contemporary spectacles that foreground the interactivity of spectators and the sensuous (Darley 4-7). Andrew Darley argues digital image cultures are distinct because they abandon the possibility of representation, in favor of calling attention to themselves as images that provoke sensation through form, style, and genre (124-44).

As critics who share an interest in civic practices and the relationship between digital rhetorics and public culture, our attention to digital photography is situated in relation to media cultures of protest; indeed, we recognize that digital photography may be inclusive of a broad range of meanings, even as our analysis highlights the meaning of digital photography when appropriated in practices of protest. In our consideration of photographs produced alongside encampments of OWS, the activities of protestors in Ferguson and Hong Kong, we have worked to understand what theories of digital rhetoric emerge through the practice of digital photography when contextualized by civic practice. In these cases, photographs in large measure produced by digital cameras or smart phones and other devices circulate through dynamic ecologies between physical places, device storage and clouds, social networking sites, and other forms of digital archiving. And although we agree that the meaning of “photography” is remediated relative to the ubiquity of digital technologies and practices, we hope to emphasize how civic practices, enabled by digital photography in protest, necessitate attention to particular conventions. To do so, we want to specify a preliminary understanding of how we situate digital photography in a new media context by delineating two registers by which we understand remediation as both a technological and social theoretical problem.

First, conventions of digital photography are over determined by their technological contexts, delimiting a rhetorical understanding. In many ways, notions of software-based “manipulation” are animated by the digital imagination of photography. Yet, considering how photography operates as a set of relations between bodies, technologies, and political imagination, we find that digital photography is distinct from genres such as computer graphics because photographic conventions developed by analog usage take precedence in the interpretation of images (Bolter and Grusin 105). The interpretive conditions of photography depend on the replication of analog conventions in orientating devices, such as the face of a camera body in a camera phone app, the reiteration of the analog camera body, the sound of a clicking shutter, viewfinders, aperture settings, and more.

So although the ubiquity of digital photographic practice relies on analog conventions, digital technologies exacerbate anxieties relative to photography’s realist and representational burden. Such is “the Photoshop problem,” in which a digital imagination suggests that photographs be evaluated on the grounds of “truth” or “deception.” For example, we find this imagination guides W.J.T. Mitchell’s normative declaration that digital manipulation ushers in the “post-photographic” era in which photography loses its capacity to perform an indexical function (225). In contrast, Bolter and Grusin suggest digital photography may be evaluated on the basis of its proximity to a realist aesthetic. For them, remediation calls attention to both desires for and the representation of immediacy, or how a particular medium invites a realist imagination (Bolter and Grusin 110). For us, the stakes of a first register of remediation foreground the problem of interpreting the photograph rather than the fuller social and political context of relations that encompass photography as we discuss here.

A focus on how technologies supplant each other as photography shifts from analog to digital cultures of production, use, and circulation helps critics understand the affordances of each in terms of the practices they enable. And yet we might at the same time lose sight of how digital photography may be situated within particular political and social contexts. Although the first register highlights technological concerns, a focus on critical spectatorship works alongside remediation as a complex social theoretical question. Two different social contexts underscore this point. First, in contrast to Bolter and Grusin, Michelle Henning considers photography as “not so much a medium as a social practice that makes use of a range of different materials and means” (50). Henning displaces a tendency to treat remediation as a property of technology, and instead foregrounds the social relations and cultural values embedded within representation. A cultural and political orientation toward remediation thus “recognize(s) that technological changes are never just material changes or even changes in ways of seeing, but ‘altered processes and relationships in basic material production’” (Henning 49). From Henning’s perspective, remediation may trace the transformation of photographic practices in terms of changes in production, circulation, and the exchange of commodities. Second, working in an ethnographic context, Ilana Gershon notes that media ideologies and perception of media shift relative to specific contexts of use, arguing that “remediation affects practice” (120-21). Together, Henning and Gershon encourage rhetorical theorists to evaluate how the ubiquity of digital camera technologies—from singular cameras to mobile devices—alters the ways in which images are produced, used, and circulated. In particular, our aim is to understand the remediation of civic spectatorship in contexts that couple photography and performances of dissent.

We find these correctives particularly compelling alongside more recent scholarship in political theory that embraces visuality as a constitutive mode of citizenship and public culture (Azoulay Civil Contract; Azoulay Civil Imagination; Hariman and Lucaites No Caption Needed; Hariman and Lucaites The Public Image; Green). What is missing in Henning’s and Gershon’s accounts is how practices of remediation might enable a more robust understanding of the photographic practices indexed by appeals to “post-occupy” cultures of photography and dissent. The shift to visual digital rhetorics of civic practice, then, directs our concentration from the medium to ask what digital photography might do in the context of social protest. As an interface, photographs circulated by protestors feature repetitive conventions in which they are aware of their participation in a broader network and media ecology. The performance of individual photographs depends on their relation to a movement’s media culture: platform delivery, captions, uptake, speed, and audience.

In what follows, we highlight three visual tropes that call attention to an emergent digital rhetoric of spectatorship: indexicality, circulation, and repetition.[5] While our analysis only engages one exemplar of each of these tropes, we offer multiple illustrations of each trope in the appendix to demonstrate their repeated appearance in vernacular OWS digital photography. We gesture toward this context of mobilization, circulation, media flow, and spectatorship because it resituates the hermeneutics of suspicion that characterizes digital photography, foregrounding instead how digital photography in social protest actively generates new norms of publicity.[6] These norms reformulate the hierarchy between actors and spectators, by drawing attention to mobile practices in which spectatorship becomes a performative action.

Indexicality / Street Portraits

Photographic indexicality refers to the sense in which photographs—at least those produced by analog technologies—document some “real” physical presence they have at least partially captured as “direct physical imprints of the reality recorded in them” (Messaris x). In this sense, photographs are interpreted to function as a kind of evidence to the true nature of the objects or events depicted (Winston and Tsang 453-69). The indexical function of the photograph offers a particularly powerful resource to protestors and advocates who seek to provide a public audience with compelling proof of the harms they oppose. The photograph affords such advocates one of the most easily transported and reproduced types of evidence to present to the public because such images are understood as relatively reliable and truthful depictions of the content they present.

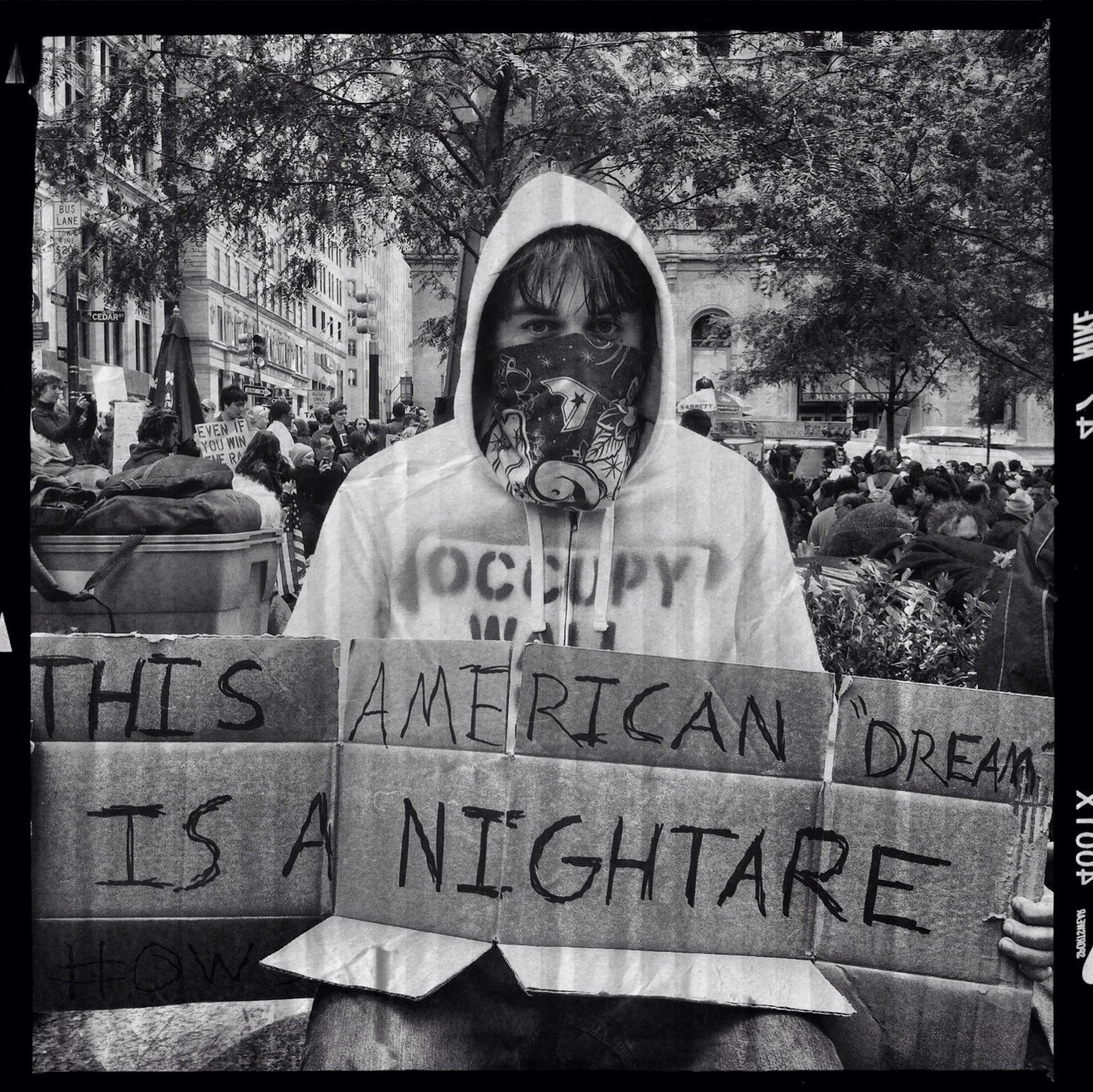

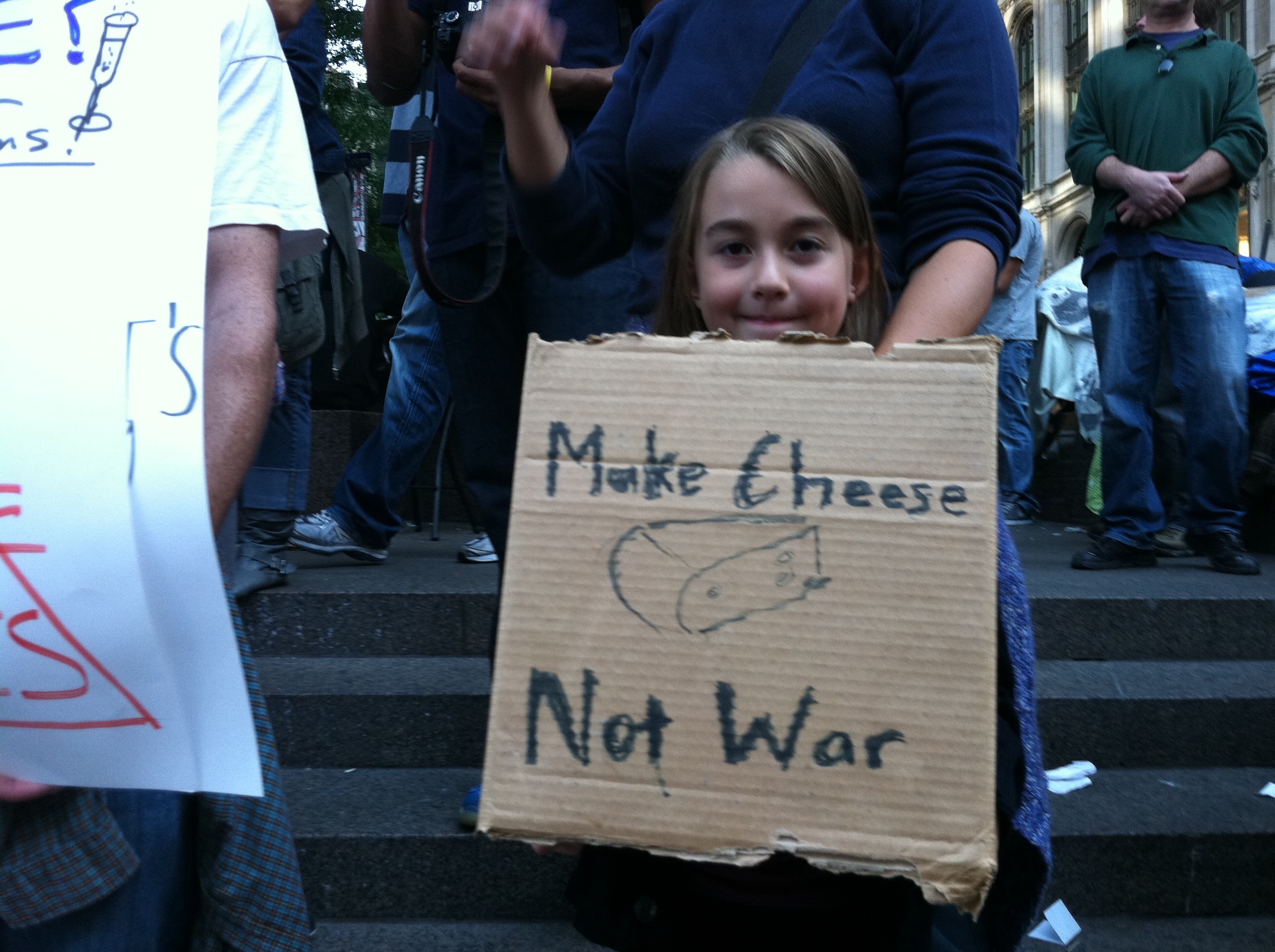

The first major convention of OWS photography appears in images we call “street portraits.” In such photographs, the viewer can see OWS protesters engaged in a form of public demonstration fairly typical of protest movements more generally. OWS participants hold signs whose quips, slogans, and short narratives address a wider public audience to articulate the participants’ grievances and demands. Humorous statements like “Make cheese not war” (The Whistling Monkey, “Occupy Wall Street 2063”) appear with the same frequency as more somber indictments of the political system, such as “Democracy not plutocracy,” and “A corporation is not a person until we can execute one!!” (The Whistling Monkey, “Occupy Wall Street 2058”). Some signs reproduce famous quotations, as seen in the photograph of a woman wrapped in an American flag and displaying a piece of a cardboard box that reads, “‘The only stable state is the one in which all are equal before the law.’ – Aristotle” (Atomische * Tom Giebel). Others advance an indictment to be considered by viewers: “If a corporation were really a person it would be a Sociopath” (Staples). Many signs invoke the now famous description of the 99% battling the 1% for resources and political influence, and protesters’ signs often explicitly mark their intended circulation through social media by including references to specific websites and social media platforms. The design of the signs varies as widely as the individuals holding them: some are obviously composed and produced ahead of the protest, printed using computer technology or stencils and cutouts that lend a more professional appearance. Others seem to have been hurriedly constructed at the site of protest using whatever materials were on hand. Despite these differences, street portraits document an overwhelmingly popular approach embraced by a majority of OWS participants.

“This American Dream,” a photograph circulated by Flickr user ShelSerkin, typifies these core elements of the street portrait convention.

Image from Flickr, user ShelSerkin, “This American Dream,” October 19, 2011

The protester featured in the photograph unambiguously marks a personal affiliation with the larger movement, wearing a hoodie emblazoned with the OWS name, displaying a sign that includes the OWS hashtag, and posing for the portrait in the public space where other protesters have gathered to articulate their outrage. The sign appears hastily constructed from a dissembled cardboard box, and the misspelling in the message and sloppy lettering suggest little forethought. Orally muted by both the mask-like bandana and the photographic text disseminating the verbal message, the protester seems to rely on the hand-lettered sign to “speak” to the audience. The bandana may call to mind other types of masks frequently appearing to obscure the personal identity of protesters: a popular choice for OWS protesters has been the Guy Fawkes masks associated with the anarchist group Anonymous, since these masks function both as a political statement and as a protective barrier against detection (Knafo). Beyond this association with an image widely circulating in popular culture, the bandana may further invoke the archetypal participant in foundational theories of the public sphere. In obscuring the protester’s identity, the bandana can visually perform the type of status-bracketing work that Habermas identifies as an essential function of the bourgeois public sphere. Like Rawls’s “veil of ignorance,” the bandana works to ensure that we interact with the protester through the message alone, rather than having our judgment of the protester’s argument colored by irrelevant identity markers (118-123).[7]

The photograph is a study in visually constructed tensions: the distance separating the central protester and the viewer suggests an intimate relationship and personal disclosure, yet the park setting calls to mind the stranger relations that are more characteristic of public interactions. The majority of the image is given over to the single protester’s figure, seeming to direct our attention to individual figures within the OWS landscape, yet a mass of protesters fills the background of the photograph.[8] Most compellingly, the image constructs a tension between the two forms of address it accommodates: the protester verbally addresses the audience through the assertion that “This American ‘Dream’ is a night[m]are,” while at the same time visually addressing the viewer through a direct gaze into the camera’s lens. As spectators, viewers of the photograph appear to be invited to consider the implications of these two forms of address. Street portraits like this one depict rather than resolve the conflict between speaking and seeing as citizens, but in doing so, they lay the foundation for evolving OWS visual conventions that begin to delineate the boundaries between these two civic modes.

In a more general sense, street portraits also prompt a reconsideration of photographic indexicality as they simultaneously mark their reliance on digital technologies and their remediation of analog conventions. In “This American Dream,” we see an image that explicitly features the facts of its digital production and circulation: the photograph uses an easily recognized Instagram filter and is distributed to the public through the photo-sharing site Flickr. Yet it also embraces the conventions of analog photography, specifically studio portraiture, that poses the protestor’s body in a familiar stance and borrows on the simultaneously nostalgic and realist aesthetic of the portrait. The duality of this image may prompt us to recognize that critiques of digital technologies that mourn the loss of indexicality may be a bit too hasty. As Tom Gunning explains, the suspicion of digital images because of their relatively easy manipulability does not necessarily indict their indexicality. In fact, this argument relies on an inaccurate assessment of traditional camera technology:

The claim that the digital media alone transforms its data into an intermediary form fosters the myth that photography involves a transparent process, a direct transfer from the object to the photograph. The mediation of lens, film stock, exposure rate, type of shutter, processes of developing and of printing become magically whisked away if one considers the photograph as a direct imprint of reality (Gunning 40).

If an assumption of indexicality assures us that what we are seeing in an image is real and authentic, then emerging practices of digital (protest) photography appear to borrow on that sense of authenticity by repurposing analog conventions, as we have seen in “This American Dream.” Mimicking the conventions that imply the indexicality of analog photographs might afford digital images an otherwise unattainable ethos of authenticity in the eyes of viewers, and in that sense, indexicality may still exert powerful influence over the design and distribution of images. Thus, even though as critics we may acknowledge that the photograph—analog or digital—does not contain original traces of a photographed event, for networked publics, the convention of indexicality potentially moves audiences.

Circulation / Tourist Poses

Attending to the circulation of photographs means, in the most basic sense, paying attention to how they move through time and space. Circulation calls attention to the various audiences photographs encounter and how their meanings emerge and evolve in relation to context (Hariman and Lucaites, No Caption Needed). In this sense, circulation “refers to spatio-temporal flows, which unfold[s] and fluctuate[s] as things enter into diverse associations and materialize in abstract and concrete forms” (Gries 335). And yet circulation should not be conceived separately from rhetorical production or composition. In other words, circulation does not occur after a text is complete; instead, “circulation and composition are inextricably linked, demonstrating how the rhetorical canons of invention, arrangement, and delivery all inform each other within a composing situation” (Penney and Dadas, 77; see also Brooke 169-93). Circulation thus becomes a powerful factor in determining both the shape and fate of protest rhetoric/photographs.

The second photographic convention of OWS images that we examine in this essay features tourists posing in close proximity to protest sites and activities. Zuccotti Park frequently appears as the backdrop of the photographs, as tourists from around the world traveled to gawk at the spectacle of OWS encampments, participants, and events. In these images, we see individuals who seem to pose as if they were standing in front of a famous monument or historical site. We could, for example, easily swap out the Grand Canyon for Zuccotti Park as the backdrop for many of these photographs and the tourists positioned in the foreground would nevertheless look perfectly in place. The tourist pose images stand out among OWS photographic conventions because of the schizophrenic juxtaposition of happy tourists smiling for the camera and protestors seeking to draw the public’s attention to grave social injustices. Where other protest conventions demand the viewer’s reflection and judgment, tourist pose images seem designed instead for indiscriminate circulation. They are constructed as artifacts that may enable the continuous retelling of the tourists’ experience visiting—but not necessarily engaging—the OWS protests.

In “Occupy Wall Street – Tourist Photo Site,” Flickr user JoshC circulates an image of two women being photographed by a third as they position themselves in front of the Zuccotti Park occupation.

Image from Flickr, user JoshC, “Occupy Wall Street – Tourist Photo Site,” October 4, 2011

None of the women appear to take notice of the OWS protester seated on the ground behind them, whose sign implores them (and the public) to “wake up.” The women in the quilted jackets pose together as if they are standing in front of a stationary monument or landmark, adopting the informal posture typical of snapshots taken while on vacation. Their depicted indifference to the activity going on behind them imposes a homogeneity on the diverse forms of protest available on the scene: for example, it is the collection of hand painted signs that come together to form the backdrop for this tourist snapshot, rather than the particular messages on those signs, that seems to matter. The women appear to be so focused on enacting the ritual of tourist photography that they seem not to notice their intrusion on the scene that casts OWS as a meaningless spectacle; notice, for example, that one woman has backed up to the point that she is standing on one of the signs spread on the ground. Such visual habits—ones that document presence without calling for reflection or judgment on the scene inhabited—seem to be at odds with the work the protesters are doing in appearing in public to call for greater scrutiny of the status quo. The composition of the image directs attention to the act of photography, and yet the image nevertheless relies on a realist aesthetic that purports to be a transparent representation of the scene unfolding before the camera’s lens. The tourists appear to pose for a photograph that will provide a record of their visit to NYC, and Flickr user JoshC, it seems, has unobtrusively preserved that moment with his own camera.

Tourist photographs document the presence of the tourist at particular locations as if simultaneously to assert and evidence a visitor’s claim that “I was there,” yet these images distance the tourists’ participation from protest action. Such images thus also operate within the conventions of snapshot photography, constructing nostalgic, visual reminders of past experiences and milestones (West). The camera technology that produces such evidence is not typically featured in the image, thus underscoring the transparency of the image and encouraging the viewer to understand the photograph itself as an uncomplicated and free-floating residue of the original experience. In the OWS images, however, we see something different: photographs that seem to call attention to the technology itself and its use in forming particular types of interaction. While these tourist interactions do little at this point to inspire reflexive judgment of the event of photography, they do begin to chip away at the façade of transparency and objectivity so ingrained in our understanding of the technology based on the conventions of photojournalism.

This specific photograph really gives us two images to consider: there is both JoshC’s image of the tourists’ photographic ritual as well as the implied image that will result when the depicted photographer snaps the picture of her two companions posing in front of the signs. The difference in circulatory intent apparent in these two images should prompt us to reconsider circulation in the context of digital protest photography. For the tourists, there is an inevitable circulation of their Zuccotti Park snapshot that results from our habits of using analog tourist photography. Long after the vacation is over, tourists are accustomed to retelling their adventures to family and friends with the assistance of the photographs they have developed and arranged. In this way, analog images function as both a narrative prompt and as documentary evidence of the events that occurred during the trip. Circulation, in other words, occurs after the photographic process has concluded.

In digital protest photography, on the other hand, circulation is a primary concern from the start. Like the OWS participants, protestors using digital technologies can create messages designed to move through online space and audiences as quickly and widely as possible. Circulation does not have to come into play after the photographic process has concluded but instead as an immediate consideration from the moment of production. Digital devices enable nearly simultaneous capturing and sharing, which means that the intent to circulate may factor into the production of the image as well as its eventual fate. The photograph by JoshC above aptly illustrates the implication of the revised sense of circulation: where the tourists are relatively oblivious to the actors and events outside their staged image, the protestors appear to strategically marshal circulatory potential in order to prompt reflexive spectatorship.

Repetition / Doubled Frames

In general terms, repetition allows a rhetor to emphasize or amplify a particular element of the message by featuring it a number of times in succession. Repetition draws the audience’s attention to a key symbol or theme by returning to it more than once. As a verbal device, repetition functions in figures too numerous to list but ranging from alliteration to polyptoton; visually, repetition appears most prominently in the meme, “a virus-like cultural artifact that proliferates by replication and mutation” (Hahner 153). Hence, repetition may occur within a single artifact, such as the duplication of symbols or sounds in verbal rhetorical figures, or across many iterations, as an image is taken up repeatedly by many individuals and replicated for new audiences.

The final variation in OWS photography that we examine in this essay involves the viewer of the photograph in the relational scene created by camera use. Here we see images that involve a double framing, in which the screen or lens of camera technology becomes a central feature of the photograph itself. These images position their viewer either in the perspective of the photographer or the perspective of the photographed subject, marking a relationship that is not unfolding in front of the viewer but one in which the viewer can play an active part.

Flickr user PaulSteinJC’s October 1, 2011 image, aptly captioned “Watching Them Back,” illustrates these doubled frames that complicate the positioning of the viewer of the photograph.

Image from Flickr, user PaulSteinJC, “Watching Them Back,” October 1, 2011

Much of the image beyond the camera in use remains blurry, but there is a clear focus on the hands holding the camera and the scene displayed on its screen. In this photograph, we may become aware of a layering of perspective through the doubled frames: just as our entry into the event is bounded by the frame of “Watching Them Back,” the entry of the OWS protester is bounded by the frame of the camera screen. Such images can call attention to the active dimensions of photographic viewing, as the spectator appears to be the force framing and interpreting the action of the image. The title of the image implies a power in watching, agency that can be harnessed and mobilized by spectators who are typically the subject of a surveying gaze. And just as the OWS protesters depicted in “Watching Them Back” seem to become aware of and then utilize such spectator power, the photograph may further encourage reflection on our spectatorship outside the moment of OWS demonstrations. The spectator of the photograph thus can encounter an opportunity to join in the multilayered relations constituting this photographic event, which extends beyond the specific time and place of its original production. The appearance of doubled frames in this way makes the seemingly discrete positions of photographer and photographed, actor and spectator, and present bodies and later viewers blur into a spectrum of positions within the event of photography that continue to be made available through the circulation of photographs.

More significantly, the doubled frames trope extends the reflexivity of spectatorship to a figure often considered separate from the action of the image: the viewer of the photograph. Doubled frames can call attention not only to the artificial construction of the image (and the embedded image captured within it), but also to the similarly overlapping layers of spectatorship that encompass witnessing of the image as well as witnessing of the event. As the OWS images may construct a visual argument for a kind of critical spectatorship that might address the inequalities that trouble the protesters, they also can invite the viewer of those images to reconsider her own spectatorship of the photograph and her relation to the public sights and citizens it presents.

It is this potential multiplying of perspective that complicates the sense in which repetition operates in the context of digital protest photography. Repetition can simply indicate featuring the same sound, symbol, or theme several times in succession, achieving an amplifying effect through the addition of utterances. However, in the doubled frames photographs we have examined, we see how digital protest photography may suggest a different sense of repetition: one where effects are multiplied instead of accumulated. Specifically, these doubled frames images appear to prompt a layering of spectatorial perspectives that fundamentally changes each as the viewers of the photograph can be invited to imagine themselves occupying several spectator positions simultaneously.

In enabling a multiplicity of perspective, rather than an accumulation of additional perspectives, repetition in the context of digital protest photography may also differ from replication. Images like “Watching Them Back” do not aggregate individual spectator positions that are produced through replication, but instead repeat the frames that demarcate individual perspectives, juxtaposing them and seeming to invite reflection on the nature of spectatorship and action. As such, the repetition apparent in photographic conventions like doubled frames exists as a challenge to the realist aesthetic that seeks to erase the technology that produces the image. Repetition in realist images—like those produced by photojournalists, for example—reinforces a traditional notion of indexicality in reassuring the viewer that the repeated element indexes some reality external to the photograph. The photograph, in this view, is a transparent, mechanical reproduction of the sights it captures. In the context of digital protest photography, repetition does not reinforce indexicality but instead complicates it, calling attention to the constitutive nature of perspective and spectatorship.

Digital Rhetoric for the Post-Occupy World

As the vernacular photography of OWS encourages us to rethink notions of indexicality, circulation, and repetition in a digital context, it also instructs a public audience in the habits of the seeing citizen, one who participates in civic life often by simultaneously occupying the positions of actor and spectator. Digital camera technologies and social media networks enable a new kind of civic practice that upends the traditional separation between those who act and those who see, making it possible for acts of seeing to fulfill the political functions of both rhetor and audience. We have argued that OWS protest photography remediates analog conventions in a digital context and shores up visual conventions that spread and make their appearances in images of subsequent protests around the world. In doing so, OWS evinces a potential impact in shaping the rhetorical practices adopted by citizens engaged in political dissent. Far from being a movement that only “fizzled out” into irrelevance, then, OWS represents an important force driving the development of contemporary protest practice enabled by digital technologies while simultaneously borrowing from the dynamic media ecologies of previous protest movements. Two features of this development stand out as particularly significant for the study of digital rhetoric: the civic pedagogy of active spectatorship, and the expansion of public rhetoric beyond institutional discourses. We conclude by reflecting on each of these in turn.

Grappling with the changes to rhetorical theory and practice introduced by electronic media, Richard Lanham notes that one of the primary, immediate effects of the technological transition is the recalibration of our attention to our own acts of seeing. Vacillating between looking “THROUGH” and “AT” texts, audiences of the electronic word encounter “graphical and typographical tricks to which the electronic surface lends itself [that] make us self-conscious again about our own apparatus of vision.”[9] Lanham argues that digital media make the “perceptual field of the ‘reader’ … considerably richer and more complex,” in no small part because of our layered vision as we become simultaneously aware of the content being presented and the presentation itself (73).

The remediation of analog photographic conventions apparent in the street portrait, tourist pose, and doubled frames images from OWS protests confirm and extend Lanham’s observation. In these images, viewers’ attention is directed not just at the content and presentation of the image, but at their own spectatorship as well. In this sense, the audience of the OWS photographs experiences a triply complex and layered perspective as they are taught to look at, through, and with photographic texts. Had the photographs simply repeated but not altered analog conventions, or presented images that made no reference to earlier photographic practices, this multiplying of perspective (and the civic pedagogy it enables) would be lost. Instead, it is the remediation of earlier conventions—such as photojournalistic images of protest, studio portraiture, and snapshot photography—re-presented and circulated across networked publics that simultaneously recall familiar sights and draw the audience’s attention to their acts of recognition.

This visual civic pedagogy should further encourage us to think beyond the role of citizens as relatively passive audiences to public rhetorics emanating from governmental or institutional discourses. In her study of politics as conducted through digital media, Elizabeth Losh rightly notes that digital literacy has become a civic skill of utmost importance. Her emphasis on policy-makers’ and institutional discourse in discussing digital public rhetoric focuses her account on the messages directed to citizens. She cautions against the antidemocratic and politically repressive potential of twenty-first-century public rhetoric appearing in governments’ use of institutional branding, public diplomacy, social marketing, and risk communication. In each case, citizens appear as the potentially manipulated and silenced public audience to digital rhetorical messages that discourage open discussion and deliberation (Losh 65-77). Developing a greater degree of digital literacy for all citizens represents one way to guard against these normative failings of public rhetoric in a digital age.

We find a complementary protection in the case of OWS vernacular photography and the thicker sense of public rhetoric it invites us to adopt. While Losh highlights public rhetoric produced for mass dissemination over digital media to audiences composed of citizens, OWS participants cultivate a public rhetoric for which citizens appear in every part of the process: the creation, dissemination, circulation, revision, and reception of digital messages. In the post-Occupy landscape of civic protest, we should understand public rhetoric as including but not limited to the types of government messages modeled after mass broadcasts that Losh investigates. In doing so, we refine our vision to appreciate the enduring continuity of digital media with rhetoric’s foundational civic mission.

Appendix

Street Portraits

Image from Flickr, user The Whistling Monkey, “Occupy wall street 2058,” October 8, 2011

Image from Flickr, user Paul Stein, “Occupy Wall Street,” September 26, 2011

Image from Flickr, user Leanne Staples, “Occupy Wall Street 18,” October 12, 2011

Image from Flickr, user The Whistling Monkey, “Occupy wall street 2063,” October 8, 2011

Image from Flickr, user Renata Ginzburg, “Occupy Wall Street, NYC,” October 10, 2011

Image from Flickr, user David Shankbone, “Occupy Wall Street October 25 2011 Shankbone,” October 25, 2011

Image from Flickr, user David Shankbone, “Day 60 Occupy Wall Street November 15 2011 Shankbone 33,” November 15, 2011

Tourist Poses

Image from Flickr, user josh bis, “Occupy Wall Street – tourist photo site,” October 4, 2011

Image from Flickr, user Scott Lynch, “Occupy Wall Street: Day 73, Zuccotti Park, Tourists on Broadway,” November 28, 2011

Image from Flickr, user Mark Lyon, “Occupy Wall Street – Tourists Watching,” September 25, 2011

Image from Flickr, user Scott Lynch, “Occupy Wall Street: Day 1, NYPD taking holiday snaps,” September 17, 2011

Image from Flickr, user Scott Lynch, “Occupy Wall Street: Day 1 NYPD photo-op,” September 17, 2011

Image from Flickr, user a c o r n, “Occupy Wall Street: Rockettes,” October 9, 2011

Doubled Frames

Image from Flickr, user Bobi Dojcinovski, “Occupy Wall Street – New York,” November 20, 2011

Image from Flickr, user Gijs Joost Brouwer, “Occupy Wall Street – March to Times Square,” October 15, 2011

Image from Turnstyle News (blog), gallery accompanying post by Miguel Macias, “Capturing the Occupy Wall Street Movement One Camera at a Time,” October 17, 2011

Image from Turnstyle News (blog), gallery accompanying post by Miguel Macias, “Capturing the Occupy Wall Street Movement One Camera at a Time,” October 17, 2011

Image from Turnstyle News (blog), gallery accompanying post by Miguel Macias, “Capturing the Occupy Wall Street Movement One Camera at a Time,” October 17, 2011

Image from Occupy for Accountability (blog), accompanying post by user CJ, “How Cell Phone Cameras Shape OWS,” October 26, 2011

[1] For a discussion of citizens’ visual habits and their centrality to democratic culture, see Allen, Talking to Strangers.

[2] Thus we take Ariella Azoulay’s work as a key orientation for our inquiry. Azoulay, A Civil Contract; Azoulay, Civil Imagination.

[3] See also Earl and Kimport, Digitally Enabled Social Change; Bennett and Segerberg, “The Logic of Connective Action.”

[4] We have in mind here something akin to the rhetorical practices theorized in Michael Warner’s account of counterpublics. See Warner, Publics and Counterpublics.

[5] On visual tropes, see Hariman and Lucaites, “Visual Tropes.”

[6] See also Cram, Loehwing, and Lucaites, “Civic Sights.”

[7] The choice to render this photograph in black and white further contributes to the sense in which the photographed subject replicates the ideal of the liberal public sphere. Whereas color signifies emotion and passion, elements typically considered to be contaminations of pure public reason because they are so often linked to subjective affective states, a black-and-white image invokes the depersonalized objectivity heralded as a necessary condition for the exercise of public reason or rational-critical debate.

[8] In “This American Dream,” the background and foreground stand in equally clear focus, a hallmark of the realist aesthetic that aims to achieve a form of representation understood to be objective and stylistically transparent. As we will see in later sections, however, variations in focus between the foreground and background come to be used strategically to direct attention away from the scene of the encounter to the camera technology being used by depicted photographers.

[9] The all-caps emphasis of “AT” and “THROUGH” are Lanham’s, used periodically throughout the book.

Allen, Danielle S. Talking to Strangers: Anxieties of Citizenship since Brown v. Board of Education. U of Chicago P, 2004.

Atomische * Tom Giebel, “Occupy Wall Street,” Flickr, 2011, https://flic.kr/p/axFbQP.

Azoulay, Ariella. The Civil Contract of Photography. Zone Books, 2008.

---. Civil Imagination: A Political Ontology of Photography. Verso, 2012.

Bellafante, Ginia. “Gunning for Wall Street, with Faulty Aim.” New York Times, 25 Sept. 2011.

Bennett, W. Lance and Alexandra Segerberg. “The Logic of Connective Action.” Information, Communication & Society, vol. 15, 2012, pp. 739–768.

Bolter, J. David, and Richard A. Grusin. Remediation: Understanding New Media. MIT P, 1999.

Bratich, Jack. “Occupy All the Dispositifs: Memes, Media Ecologies, and Emergent Bodies Politic.” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, vol. 11, no. 1, 2014, pp. 64–73.

Brooke, Collin Gifford. Lingua Fracta: Toward a Rhetoric of New Media. Hampton P, 2009.

Costanza-Chock, Sasha. “Mic Check! Media Cultures and the Occupy Movement.” Social Movement Studies, vol. 11, no. 3-4, 2012, pp. 375–385.

Cram, E., Melanie Loehwing, and John Louis Lucaites. “Civic Sights: Theorizing Deliberative and Photographic Publicity in the Visual Public Sphere.” Philosophy & Rhetoric, vol. 49, no. 3, 2016, pp. 227–253.

Darley, Andrew. Visual Digital Culture: Surface Play and Spectacle in New Media Genres. Routledge, 2000.

Earl, Jennifer, and Katrina Kimport. Digitally Enabled Social Change: Activism in the Internet Age. MIT P, 2011.

Feffer, Leslie. “Notes from Wall Street Occupation Zone; Bringing Back the '60S Commune to Fight for Something or Other.” Washington Times, 7 Oct. 2011, http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1g1-268979288.html?refid=easy_hf.

Fisher, Max. “Hong Kong's Protesters Are Using the Same 'Hands up, Don't Shoot' Gesture Used in Ferguson.” Vox.com, 28 Sept. 2014, http://www.vox.com/2014/9/28/6860493/hong-kong-protests-mike-brown-ferguson.

Gershon, Ilana. The Breakup 2.0: Disconnecting over New Media. Cornell UP, 2010.

Gladwell, Malcolm. “Small Change.” The New Yorker, 4 Oct. 2010.

Glantz, Gina. “To 'Occupy' and Beyond.” Washington Post, 31 Dec. 2011, http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1p2-30412646.html?refid=easy_hf.

Green, Jeffrey E. The Eyes of the People: Democracy in an Age of Spectatorship. Oxford UP, 2010.

Gries, Laurie E. “Iconographic Tracking: A Digital Research Method for Visual Rhetoric and Circulation Studies.” Computers and Composition, vol. 30, no. 4, 2013, pp. 332–348.

Griffin, Anna. “Ferguson Protesters in Portland Seek to Build on, Learn from Occupy Wall Street Movement.” Oregonian/Oregon Live, 1 Dec. 2014, http://www.oregonlive.com/portland/index.ssf/2014/12/ferguson_protesters_in_portlan.html.

Gunning, Tom. “What's the Point of an Index? or, Faking Photographs.” Nordicom Review, vol. 1-2, 2004, pp. 39–49.

Habermas, Jürgen. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. MIT Press, 1991.

Hahner, Leslie A. “The Riot Kiss: Framing Memes as Visual Argument.” Argumentation and Advocacy, vol. 49, no. 4, 2013, pp. 151–166.

Hariman, Robert, and John Louis Lucaites. No Caption Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy. U of Chicago P, 2007.

Hariman, Robert, and John Louis Lucaites. The Public Image: Photography and Civic Spectatorship. U of Chicago P, 2016.

Hariman, Robert, and John Louis Lucaites. “Visual Tropes and Late-Modern Emotion in U.S. Public Culture.” Poroi, vol. 5, no. 2, 2008, pp. 47–93.

Henning, Michelle. “New Lamps for Old: Photography, Obsolescence, and Social Change.” Residual Media, U of Minnesota P, 2007.

Holland, Joshua. “How Cellphone Cameras Shape OWS.” Salon.com, 26 Oct. 2011, http://www.salon.com/2011/10/26/how_cellphone_cameras_shape_ows/.

Johnson, Theodore R. “The Ferguson Movement Has Too Much to Do—Don’t Let It Fizzle Out Like Occupy Wall Street.” The Root, 1 Dec. 2014, http://www.theroot.com/articles/culture/2014/12/don_t_let_ferguson_fizzle_like_occupy.html.

Knafo, Saki. “Occupy Wall Street And Anonymous: Turning a Fledgling Movement into a Meme.” The Huffington Post, 20 Oct. 2011, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/10/20/occupy-wall-street-anonymous-connection_n_1021665.html.

Kristof, Nicholas. “Bankers and Revolutionaries.” International Herald Tribune, 3 Oct. 2011.

Lanham, Richard A. The Electronic Word: Democracy, Technology, and the Arts. U of Chicago P, 1993.

“Letters: Advice for Occupy Wall Street.” USA Today, 20 Sept. 2012, http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/opinion/letters/story/2012-09-19/occupy-wall-street-growth/57809630/1.

Losh, Elizabeth M. Virtualpolitik: An Electronic History of Government Media-Making in a Time of War, Scandal, Disaster, Miscommunication, and Mistakes. MIT P, 2009.

Macias, Miquel. “Capturing the Occupy Wall Street Movement One Camera at a Time.” Turnstylenews, 17 Oct. 2011, http://turnstylenews.com/2011/10/17/capturing-the-occupy-wall-street-movement-one-camera-at-a-time/.

Madhani, Aamer, and Yamiche Alcindor. “Ferguson Has Become a Springboard for Many Movements.” USA Today, 8 Dec. 2014, http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2014/12/05/ferguson-protests-broaden-occupy-wall-street/19917015/.

Messaris, Paul. Visual Persuasion: The Role of Images in Advertising. Sage Publications, 1997.

Mitchell, William J. The Reconfigured Eye: Visual Truth in the Post-Photographic Era. MIT P.

Nielsen, Rasmus Kleis. “Mundane Internet Tools, the Risk of Exclusion, and Reflexive Movements-Occupy Wall Street and Political Uses of Digital Networked Technologies.” Sociological Quarterly, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 173–177.

Penney, Joel, and Caroline Dadas. “(Re)Tweeting in the Service of Protest: Digital Composition and Circulation in the Occupy Wall Street Movement.” New Media & Society, vol. 16, no. 1, 2014, pp. 74–90.

Rawls, John. A Theory of Justice. Revised ed. Harvard UP, 1999.

Sorkin, Andrew Ross. “Occupy Wall Street: A Frenzy That Fizzled.” New York Times, 18 Sept. 2012.

Staples, Leanne. “Occupy Wall Street 27,” Flickr, 2011, https://flic.kr/p/aH9rRe.

The Whistling Monkey, “Occupy Wall Street 2063,” Flickr, 2011, https://flic.kr/p/aug6YF.

The Whistling Monkey, “Occupy Wall Street 2058,” Flickr, 2011, https://flic.kr/p/aug68B.

Tufekci, Zeynep, and Christopher Wilson. “Social Media and the Decision to Participate in Political Protest: Observations From Tahrir Square.” Journal of Communication, vol. 62, no. 2, 2012, pp. 363–379.

Warner, Michael. Publics and Counterpublics. Zone Books, 2002.

Welch, Kathleen E. Electric Rhetoric: Classical Rhetoric, Oralism, and a New Literacy. MIT P, 1999.

West, Nancy Martha. Kodak and the Lens of Nostalgia. UP of Virginia, 2000.

Winston, Brian, and Hing Tsang. “The Subject and the Indexicality of the Photograph.” Semiotica, vol. 2009, no. 173, 2009, pp. 453–469.