Jessica E. Slentz, Case Western Reserve University

(Published July 20, 2016)

Museums have long used technology to facilitate visitor engagement, interpretation, and education. Traditionally, these interpretive technologies have taken the form of linear and top-down media—such as wall placards, audio tours, brochures and docent-led tours—which position visitors, in the words of Peter Samis, as “empty vessels” to be educated by the more culturally literate (305). Today, in addition to these linear interpretive technologies, museums are increasingly investing in emerging digital media technologies that foster interactive exhibition experiences for the purposes of both entertainment and education (Luke, Samis, Simon). Gail Anderson argues that this digital turn in new exhibition practices denotes “a fundamental shift in ideology and practice” (8) in the museum sector at large.

Central to new exhibition practices is an approach to exhibition and display that positions the museum visitor not merely as passive spectator, but rather as active participator, which in Nina Simon's words, "means trusting visitors' abilities as creators, remixers, and redistributors of content" (331). Many scholars agree that the nature of such participation can serve to redefine traditional relationships between the institution and the public, allowing today’s museum visitors access to roles and discourses traditionally reserved for a cultural elite (Haskins, Parry, Barrett, Samis). Ross Parry goes so far as to argue that new media interfaces and participatory exhibition displays are changing entrenched notions of authority and curatorship. Able to participate in interactive experiences through exhibition technology, visitors no longer have to rely solely on the institution to foster and shape their relationship to cultural artifacts, artworks, and texts. Instead, Parry argues that emerging technologies give “the means to initiate and create, collect and interpret in their own time and space, on their own terms. It amounts to nothing less than a realignment of the axes of curatorship” (102).

Not all digitally mediated interactive exhibits, however, afford the same kinds of participatory experience. Many digital exhibition technologies offer visitors multiple ways of viewing and interpreting an artifact—by providing additional educational materials, involving senses other than sight, or even incorporating game play. However, these technologies often are not revolutionary but rather facilitate the traditional interpretive hierarchy of an institution educating lay visitors in proper ways to interact with the work of art or text. Where, then, is the “paradigm shift” that new exhibition studies scholars applaud being enacted? I argue that the shift from visitor-as-spectator to visitor-as-co-producer is enacted in interactive experiences, particularly those afforded by touchscreen interfaces, which invite visitors to participate in traditionally institutional activities such as curation and response.

In this essay, I investigate and analyze the rhetorical positioning of the museum visitor as co-curator, a position that is afforded by a groundbreaking piece of touchscreen exhibition technology: the Collection Wall at the Cleveland Museum of Art in Cleveland, Ohio. The Collection Wall is located in the Gallery One exhibition space at the Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA). Designed to “seamlessly integrate” technology with the museum’s permanent collection, Gallery One, along with the CMA’s concomitant iPad app, ArtLens, features cutting-edge and one-of-a-kind exhibition media. Six touchscreen “lenses” allow visitors to virtually interact with art they could not otherwise touch by inviting them to “sculpt” clay; experiment with abstract painting techniques; search CMA’s collection using their own facial expressions; remix famous artworks into their own creations; and more. With the ArtLens app visitors can save and share “favorites,” compose tours, and follow other visitor-created tours. ArtLens operates locatively inside the museum, showing visitors what is “near [them] now,” and allows visitors to “scan” a work of art, accessing multimedia educational material that is superimposed and/or played alongside their view of the physical artifact.

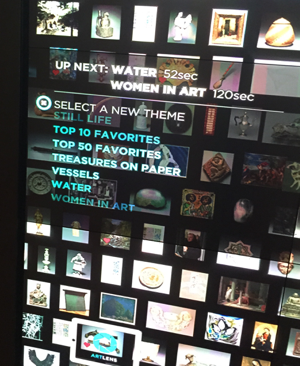

The Collection Wall is the centerpiece of Gallery One. The 5 foot by 40 foot multi-touch MicroTile digital screen impressively spans the entire wall of an exhibition space dedicated primarily to its display. The Collection Wall’s screen dynamically displays images from the CMA’s permanent collection, either in a slowly scrolling mosaic of small images (Figure 1) or curator-composed categories of larger images, rotating from one category to the next every thirty to sixty seconds. Some of the categories of images displayed are germane to the discourses of art history, such as “Funerary Equipment,” “Vessels,” and “Still Life.” Other categories organize artworks under more “vernacular” (Samis 307) designations such as “Color,” “Hats,” “Patterns,” and “Top 10 Faves.” Visitors can use the touchscreen Collection Wall to access digital images of every object on display in the museum proper, swipe through “related” artworks, browse visitor-created tours, and save “favorites” to their ArtLens app account.

Figure 1: Collection Wall

Through close analysis of the Collection Wall and its use, I will show how the habits and modes of interaction afforded by this interface offer guests a particular range of experiences both with the wall as a digital object and with the images of the museum’s permanent collection that the wall displays. I will further show that touchscreen technologies can be used by museums to foster rhetorical experiences that shift the interpretive position of the visitor, allowing the visitor to actively and publicly participate in types of activities that in the past were exclusively undertaken privately by the institution. Finally, I will show that a museum visitor’s ability to perceive affordances in touchscreen exhibition interfaces, and thus the visitor’s individual rhetorical experience, relies heavily on the visitor’s previously existing digital literacies.

Rhetorical Experience, Touchscreen Interfaces and Habits of Interaction

In order to effectively analyze the experiences made possible through interaction with the Collection Wall, I borrow from rhetorician Gregory Clark’s concept of rhetorical experience. In his essay, “Rhetorical Experience and the National Jazz Museum,” Clark proposes an “outline of a theory of rhetorical experience” (114). Merging both aesthetic and rhetorical theory by synthesizing the work of John Dewey and Kenneth Burke, Clark makes a strong case for the importance of approaching experiences—particularly the aesthetic experiences composed by various spaces and media of exhibition and display—as objects of rhetorical study. Quoting Dewey’s understanding of aesthetic experience, which interprets “aesthetic” as concerned with meaning making and human communication broadly construed (113), Clark echoes Dewey’s definition of experience as the “interaction of organism and environment which . . . is a transformation of interaction into participation and communication” (115). Experience, situated in “particular places at particular times” (116), always enacts some sort of change in attitudes, what Burke identifies as deeply held thoughts and convictions, on the part of the individual. Additionally, as “transformation” into “participation and communication,” experience is neither a passive nor a solitary occurrence. Experience in this understanding always produces a result that translates into action, and it always has social ramifications. The rhetorical work of experience, Clark argues, occurs when individual transformations “become civic in their consequences when those attitudes affect [public] identities” (118).

Clark notes that not only are rhetorical experiences lived by the interacting audience, but they are also composed, or “carefully designed” by a persuading rhetor to produce particular actions and interactions on the part of an audience (122). As such, Clark argues, experiences can be approached by rhetoricians as objects of rhetorical analysis. Clark examines a brief selection of potential experiences within the National Jazz Museum in Harlem to show how a theory of rhetorical experience might shed greater light on how audiences move through and engage with spaces of exhibition and display. He concludes that rhetorical experience, which involves simultaneous interaction with and navigation of multiple works, texts, and identifications through a wide range of sensory channels (including sound, touch, and smell), can be seen as embodied in a way that “the rhetorical work of display” cannot (132). For Clark, the rhetorical nature of aesthetic experience allows rhetoricians to critically analyze the particular moment of embodied interaction itself—being both the locus of activity and the rhetorical effects that activity produces—rather than just specific, stationary works or texts.

Touchscreen and other new media interfaces “work continually to engage the audience not simply in action but in interaction” (Carnegie 171). This moment of interaction is crucial when examining the experiences afforded by touchscreen interfaces. In order to effectively speak about the moment of interaction with an interface that comprises a rhetorical experience, we need to clearly delineate between the experience itself and the technological object at the center of such an experience. In this analysis I use the terms “interface,” “Wall,” or “Collection Wall” to refer to the physical technological object, and “images” to refer to the content that technological object serves to deliver.

Also key to evaluating the moment of interaction that comprises a rhetorical experience is a clear understanding of the affordances of the object at hand that shape one’s interaction with that object. The term “affordances” has become commonplace in digital rhetoric (Kress and van Leeuwen, Kress). However, many of these appropriations of affordances fail to articulate the important relationships between objects, affordances, and human interactions inherent in psychologist James Gibson’s original term (Lee). In The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception, Gibson defines affordances as what an environment “offers the animal, what it provides or furnishes” (127). John Sanders extends this definition by noting that affordances are “opportunities for action in the environment of an organism” (129). For Gibson, an environment is made up of both animate and inanimate objects; the animate objects, or animals (including people), perceive the affordances made available by the materiality (e.g. objects, surfaces, and other animals) of the environment. The perception or enactment of an object’s affordances is contingent on a particular animal’s understanding of a particular object and reliant on potential bodily interaction with that object. As T. Kenny Fountain explains, affordances are "the mutual contact between the object-ness of the object and our bodily capacities" (92). Thus, one’s perception of available affordances is tied to both one’s observation of the nature of the object itself, and to one’s unique interpretation of the opportunities for action made available for his or her individual body. Affordances then are opportunities not just for action but also, most importantly for my purposes here, for interaction. I will thus use Gibson’s term to examine the affordances—the opportunities for interaction—that are made possible through interaction with the Collection Wall.

The affordances of the Collection Wall, both in terms of interface design and content, direct both what the visitor can do and how they may do it. This distinction is necessary for a thorough description of the experience of interaction with the wall. Because touchscreen technology affords a meeting of the body and the computer interface, it creates an experience of “simultaneous exchange of information between the user and the machine” (Hayward et. al 18). The Collection Wall then, as a touchscreen interface, affords tactile, embodied interaction with both the interface itself and the content it displays through touch—a sensory experience and subjective position not afforded by traditional interpretive media such as audio tours. Through such embodied interaction, the affordances of the touchscreen can provoke unique habits on the part of the user/visitor (Farman 63). To analyze what a visitor can do through interaction with the wall I will use the term habits of interaction, which I explore more closely in my analysis. How a visitor may do the things the Wall invites him or her to do is determined by the various interaction modalities, such as “touch, pen, tangible objects, gaze, hand gestures and handheld devices” (MultiTaction), that it makes available as a touchscreen interface. 1

In the analysis that follows, I examine the habits and modes of interaction afforded by the Collection Wall through a closer look at the affordances a visitor may perceive it to be offering. This analysis is guided by the following questions: What interaction modalities and habits of interaction does this interface potentially make possible for the visitor?Into whatparticipatory experiences does the content and affordances of this interface invite visitors? What interpretive positions do those experiences persuade the visitor to take up? How does this interface and the experiences it affords position the visitor rhetorically in relation to the museum’s collection and to the cultural work of institution itself?

The Collection Wall at the Cleveland Museum of Art & Co-Curation

The Collection Wall in Gallery One of the CMA is currently the largest multi-touch display wall in the United States. According to the CMA’s website:

The wall is composed of 150 Christie MicroTiles and displays more than 23 million pixels, which is the equivalent of more than twenty-three 720p HDTVs. The Christie iKit multi-touch system allows multiple users to interact with the wall, simultaneously opening as many as twenty separate interfaces across the Collection Wall to explore the collection.

At the base of the wall sit eight docks that sync visitors’ tablets or phones to the wall’s database via RFID tags, allowing users to sync their favorite images and tours from the wall to their ArtLens app account (Figure 2).

Accessible directly off of the CMA’s main atrium, the Collection Wall is mounted alone on the far wall of a large, open room that allows for a sizable group of visitors to interact with the wall while other visitors pass behind them into the adjacent rooms of the Gallery One space. A small desk framed by the call to “Try the ArtLens App! Device set-up and rental” and staffed by a CMA employee sits to the right of the Collection Wall, inviting visitors to ask questions, rent iPads, or set up their mobile devices for use. 2 The space is dimly lit with recessed and track lighting, and the ceiling is lower than that of any of the museum’s other galleries, which draws the viewer’s attention directly to the wall itself. Several low, wide, modern plastic chairs sit far back at the edge of the wood floor that reflects the wall's light. The open space, the black frame in which the Collection Wall is mounted, and the viewing chairs all echo the way large paintings or sculptures are displayed elsewhere in the museum. In contrast, the floor behind the row of viewing chairs is carpet rather than wood, and there are tables with chairs set up for reading, along with several bookshelves offering a selection from the CMA’s Ingalls Library. By conflating stark display and warm research space, the surroundings of the Collection Wall create a foundation for how the visitor can approach the wall—as both art object and interpretation tool.

Figure 2: Collection Wall

The Collection Wall’s digital display is divided into two hemispheres, separated by the connecting frame; despite this screen division, it acts as one synchronous display. The display refreshes every 30 to 60 seconds, alternating between a slowly scrolling mosaic of small images (see Figure 1) that represents the CMA’s permanent collection and selected groupings of larger images. The groupings of larger images take shape as one of 32 different “curated views of the collection” (CMA), or as categories that are titled thematically (such as by time period), or by media type. There is no designation on the wall or elsewhere that tells visitors which of these categories are considered the “curated views” and which are not, with the exception of the category titled “Director’s Favorites.”

Some of these categories are constructed on a timeline, offering a historical overview of a particular theme for the viewer. Each historical overview encompasses a different, inconclusive timeline with unclear starting and ending dates. The category “Fashion,” for example, is set out from pre-1500 through post-1910, while “Mother” spans from pre-600 through post-1950. Categories displayed with a timeline present a wide scope of works in different media and create a particular heuristic through which to interpret the category. For example, the category “Mother” includes medieval paintings of the Madonna and Child, as well as more contemporary portrayals of modern motherhood in works from the early 1950’s; this conflation of works within the space of the wall’s frame suggests a link between not only “Mary” and “Mom,” but also between the religious and the secular, ancient and modern art.

In addition to such historical overviews, the display rotates through groupings based on a variety of continuums. “Color,” for instance, includes mid-sized images of various works of all media from a wide range of time periods in a spectrum that flows (left to right) from blue to yellow to taupe to red (Figure 3). Yet another display reads “Birth” in the upper left corner of the wall and “Death” in the upper right, a continuum of images constructing a narrative from the beginning to end of life, much like “Day” and “Night” which follows the same pattern. Others are organized by theme, such as “Feast,” “Dance and Music,” and “African American Prints and Drawings.” Still other categories are grouped by object or media description such as “Water” (Figure 4), “Vessels,” “Chairs,” and “Hats.” The content management system that runs the wall’s display refreshes every ten minutes, “[updating] the wall with high-resolution artwork images, metadata, and the frequency with each artwork has been ‘favorited’ on the wall and from within the ArtLens iPad/iPhone app” (CMA). All of these curated themes and categories “can be changed dynamically [by CMA curators] creating another mode of expression for staff, and connecting with temporary exhibitions or creating new ideas for the permanent collection” (CMA). Additionally, through one link in the lower left corner of the wall, visitors may “Select a New Theme.” This feature shows what category is currently being displayed and which two are set to follow (and in how much time). Here, visitors can scroll through available categories and choose which one to queue for display next (Figure 5).

Figure 3: "Color"

Figure 4: "Water"

Figure 5: "Select a New Theme"

The touchscreen interface of the Collection Wall affords visitors two primary interaction modalities beyond the visual mode of gaze; these modalities control how visitors may interact with the wall. In addition to looking at it, interpreting its content and affordance through sight in much the same way as they would with a painting or sculpture, visitors may touch it with their hands, and if they wish to, they can use their mobile devices to sync with the Wall’s digital content. However, no explanatory paratext surrounds the wall to introduce these modalities; nothing in the space communicates directly to visitors what the wall is or how they are meant to engage with it. During peak hours an employee is stationed at the iPad rental desk, but the employee usually does not give any type of instruction or introduction unless expressly asked. When a visitor enters the room, he or she will see the Wall at some point in the series of rotations that I have described. When a visitor is already interacting with the wall, often newly arrived visitors will observe their behavior and follow suit. Just as often, however, a visitor will approach the Wall alone without prior knowledge of its purpose or operation. In this case, in order to interact with the touchscreen interface of the Wall, and thus with the content displayed therein, the visitor must rely on two interconnected elements: the various habits of interaction afforded by the wall and his or her own existing digital literacies, which these habits of interaction directly reference and rely on.

Digital literacies, understood as the “practices of communicating, relating, thinking and ‘being’ associated with digital media” (Jones and Hafner 13), are learned and embodied skills as well as social practices that drive an individual’s interaction with digital interfaces and media (Jones and Hafner, Knobel and Lankshear, Kress, Selfe). The various habits of interaction that the Collection Wall affords assume particular digital literacies of their audiences, namely familiarity with touchscreen interfaces and the actions of touching, swiping, hyperlinking and favoriting.

1. Habits of Interaction: Touching and Swiping

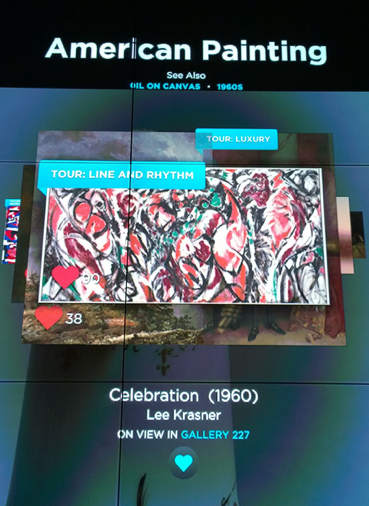

After the display of the Collection Wall refreshes, additional groupings of medium-sized images appear in various locations. These groupings resemble stacks of images, with labeling text above and below (see Figure 6). The image at the front of the stack is labeled with a blue ribbon at the top that announces one of the “Tours” that that image is included in. Underneath the image is white text that states the name of the art piece, the year it was created, and the artist’s name, followed by “On view in…” and the gallery number in which the visitor can find that piece. Finally, centered underneath the attributional text sits a blue heart icon.

When these stacks of images first appear atop the larger background display, they do so with an animation of a white hand using its index finger to swipe right or left through the stacks of images. The moving hand then presses the blue heart icon underneath the image, which causes the number to the right of the red heart icon at the bottom left corner to increase by one (see Figure 7). This swiping, heart-clicking animation continues automatically until a visitor takes over the action by touching the screen and swiping the top image on the stack.

These stacked clusters are the locus of all of the Wall’s habits of interactivity, the others of which are visually implied (rather than instructed) based on a visitor’s previously existing digital literacies. The swiping hand animation is the only instruction the Collection Wall offers visitors as to how they may interact with the Wall. While the animation models how one might swipe through the images presented, one must be at least cursorily familiar with other touchscreen interfaces that allow for finger-controlled swiping motions in order to recognize this animation as a call to action.

Figure 6: "Swipeable Image Stack"

Figure 7: "Number of Likes"

2. Hyperlink Browsing

While the attributional text below the front image of the stack is white, other lines of text designating what gallery, additional categories or tours where the artwork can be found, are blue or highlighted in blue. The blue lines of text hyperlink to different groupings of images within the Collection Wall’s database. When clicked, the hypertext links (Figure 6) replace whatever current grouping the visitor was swiping through with a new stack of swipeable, hyperlinked, likeable images. The visitor can then navigate through the available hyperlinks to see how each image is connected with other artworks throughout the museum. Rather than displaying an overt notice of this habit of interaction, the Collection Wall utilizes visitors’ previously existing familiarity with the act of browsing by displaying the font of the hyperlinks in blue, the hyperlink color currently used by Google and many other Internet search engines.

With extended use, one will see that the connections being made between art works are fluid and numerous. A visitor can follow a path from the category American Painting in the 1960’s to an image of a Baroque clock compiled under the hyperlink “Visitor Created Tour: Random Tour with Cool Stuff.” 3 However, the interface of the Wall does not afford touch-type capabilities or other ways of searching for particular themes and artworks. The database of images the Collection Wall displays can only be navigated through the predetermined algorithms of these browsable, hyperlinked categories.

3. Favoriting

The final habit of interaction the Collection Wall affords visitors is favoriting, by which visitors click the blue heart icon displayed underneath an image to indicate that they like that image. When a visitor favorites an image, the red heart in the bottom left corner of that image is animated briefly with a new heart and a “+1” sign. The red heart icon then returns to resting and the number to its right (see Figure 7) will increase by one.

When a visitor is interacting with the wall without the aid of an RFID-linked mobile device, touching the heart symbol increases the number of the hearts in this way and the word “Favorited” appears briefly across that section of the screen. Conversely, if a visitor has docked-an RFID tagged iPad in the closest one of eight docks, and is logged into their personal ArtLens account on that device, when he or she clicks the heart symbol additional text saying “Saved to Favorites” accompanies an animation of a heart traveling to the docked iPad. That image and all of its related additional education material contained in the ArtLens app is then saved in that visitor’s personal collection of favorites and can be used to discover more about the work or add it to that visitor’s tour. In this way, favoriting uses both of the unique interaction modalities that the Collection Wall affords—touch and communication with a mobile device. These modalities allow visitors to supplement their browsing experience with further interaction within the app.

Favoriting is a social and public act, as it visibly increases the number of hearts attributed to a particular work and adds visitor choices to the larger categories displayed by the Wall, particularly under the headings such as “Visitor Favorites” and “Top 50 Faves.” Like the other habits of interaction, favoriting on the Collection Wall directly engages a visitor’s existing digital literacies (or lack thereof). No text introduces “favoriting” as an available habit of interaction anywhere on or around the wall; in fact, the word “favorite” as an imperative is never used. The word “Favorited” is displayed only after the visitor touches a blue heart. The heart symbol, however, as an indication to “like” an image, is seen widely across image-centric social media sites such as Instagram, Pinterest and Tumblr. A visitor who was familiar with these sites and thus with the visual discourse of the heart symbol meaning to “like” an image, would immediately be able to view the heart as a call to action. Without that prior knowledge, however, the visitor would not necessarily make that connection.

Rhetorical Experience and Co-curation

As I have shown, the affordances of the Collection Wall at the Cleveland Museum of Art include two primary interaction modalities that dictate how visitors may interact with the Wall—physical touch with one’s hand and virtual syncing with a compatible mobile device—and four habits of interaction—touching, swiping, hyperlink browsing, and favoriting—that determine what they can do with its interface and the content it displays. These affordances then encourage viewers to take up particular roles in relation to both the Collection Wall itself and the museum proper; these roles and relationships shape the rhetorical experiences that the interface mediates.

The Collection Wall affords visitors the ability to interact with the museum’s collection in a dynamic way through swiping, browsing, hyperlinking and favoriting. The participatory nature of these experiences counters the traditional assumption that one must attain an ideal level of expertise or knowledge in order to make relational connections between disparate artworks or to publicly express one’s preference for a particular piece. The hyperlinked browsing afforded by the Collection Wall makes no indication of a hierarchy of possible tour experiences that one may browse through; “Visitor Created Tour” and “Tour” are represented the same way visually and afford the same habits of interaction. This equality of interaction capabilities implies that the experience of following a tour created by a visitor is just as important as that of following one compiled by the museum. Likewise, this interactive experience communicates to visitors that they too have the opportunity to interpret the collection through the act of putting together, naming, and sharing their own tour alongside those created by professional curators. In other words, the interactive, and thus rhetorical experience afforded by the Collection Wall persuades the visitor to see themselves in relation to the museum, not as merely a lay spectator, but as an active participant in the cultural work of the institution.

In “Interface as Exordium: The Rhetoric of Interactivity,” Teena Carnegie examines the interface itself as a locus of relational activity that does rhetorical (persuasive) work. The interface, for Carnegie, is crucially a point of dynamic interaction that “becomes central to building and determining relationships” between user and interface, user and user, and user and content (or entity managing said content). These interactive relationships ultimately affect both what one is persuaded to do and how they are persuaded to do it (165). Although Clark looks more broadly at exhibition media and spaces rather than at particular interfaces, the perceived relationships that the exhibits at the National Jazz Museum in Harlem create are the foundation for his understanding of rhetorical experience as immersive and public in nature. Relationships, in this way, are key to understanding the rhetorical experience of interactivity with an interface, and how that experience might position the user/visitor within the larger civic climate in which they are participating.

The potential relationships created by a visitor’s perception of the affordances of the Collection Wall are perhaps best illustrated by comparing the experience of browsing with the Wall to the experience of “browsing” the museum’s collection by walking through the museum proper. The experience of interactivity with art images that is afforded by Collection Wall is both spatially (within the walls of the museum itself) and experientially/sensorally (touching as well as seeing) juxtaposed to the experience of viewing the original art objects elsewhere in the museum. When walking through the various galleries in the museum, visitors experience viewing the art objects and the exhibition spaces at their leisure; they can move at their own pace, chose which gallery to visit when, consult the museum map to determine where a particular curatorial theme is located, and use audio tours and wall placards to orient themselves to a work’s meaning and/or history. What they cannot do, however, is navigate disparate categorical groupings of artworks with the immediacy and subjective power that physical touch affords (Paterson 3), what David Parisi identifies as “active touch” (319). Visitors also cannot view and interpret the displayed artworks side by side in collections imagined by their fellow visitors. Whereas a work in the museum proper is displayed in a fixed location and viewed only in relation to the institutionally curated works immediately surrounding it, the browsing and hyperlinking capabilities afforded by the Collection Wall allow for a more democratic view of how that work can be seen and interpreted in relation to other works. Additionally, and more importantly, while the experience of walking through the museum offers only one, fixed, institutional, interpretive view of the CMA’s collection, the Collection Wall (both on its own and in conjunction with the ArtLens application) expands that view beyond institutional curatorial categories and invites the visitor to participate in the position of co-curator.

The implications of this relational shift from visitor-as-spectator to visitor-as-co-curator/co-producer are salient, and their impact on the futures of both the museum and of emerging technologies in spaces of exhibition and display deserves further investigation by rhetoricians. As I have shown, the rhetorical experiences that are driving this relational shift are made possible by the affordances of the interactive technologies used to create those experiences. Parry, Anderson, and other museologists who see this move towards participation as ultimately “culture shifting,” make a strong case for the potential of such experiences to enact a democratization of cultural education, interpretation, and response. However, a closer look at the dependency of such rhetorical experiences on the habits and modes of interaction afforded by interpretive technology shows us that this shift does not come without its own set of potential roadblocks to access and cultural equity.

One’s ability to perceive the affordances, or opportunities for interaction, made possible by a particular piece of technology is another way of understanding one’s digital literacies. According to Gibson, the affordances of a particular object are connected both to a person’s knowledge of what an object is, and that person’s physical relationship with the object itself. Digital literacies are, as Lauren Bowen says, highly personal, “embodied experiences” (589), that are dependent on an understanding of what a particular interface is and how it is possible to use it. When interacting with digital technology, users will experience different types and levels of engagement due to disparities in age (Bowen, Haddon et. al), physical ability (Walters), socio-economic status, access to personal technology, and other factors that can affect one’s acquisition of digital literacies (Selfe).

As I have demonstrated through analysis of the Collection Wall, the rhetorical experience of the visitor-as-co-curator is made possible by the habits and modes of interaction that the Wall's particular interface affords. However, the availability of these habits and modes of interaction is dependent on whether or not the visitor possesses the digital literacies necessary to perceive them as affordances. Thus, the potential rhetorical experiences a visitor may or may not participate in through interaction with digital interpretive technologies rely on that visitor’s previously existing digital literacies and physical ability. In the case of the Collection Wall, in order for a visitor to participate in the experience of co-curation, he or she must first have access to a mobile device capable of supporting the ArtLens application. If the visitor neither has such a device personally nor is able to rent one for the day from the museum, he or she, though potentially able to “favorite” an image by touching the Wall, will be unable to translate the habit of interaction of favoriting into the act of creating a tour for others to follow. If a visitor is unfamiliar with the popular social networking genre conventions employed by the Wall’s content, such as hearts and “favorites,” he or she may not interpret favoriting as social or participatory action at all. If one is unfamiliar with the habits of browsing, swiping, and hyperlinking—habits of interaction afforded by other popular touchscreen devices—that visitor’s potential to view and interpret art through the more vernacular and democratic categorizations and relationships the Wall makes possible will be less than that of a visitor who is. Additionally, the mode of interaction with the Wall through touch requires certain bodily actions on the part of the visitor; some visitors may be, for a variety of reasons, physically unable to engage in the habits and modes of interaction others perceive the Collection Wall as affording, and thus some visitors will not have access to the same rhetorical experiences as others.

Exciting new participatory experiences are indeed being made possible through touch-screen interpretive technologies such as the Collection Wall; at the same time, when we examine the habits and modes of interaction those technologies afford more closely, we see that there are particular users and bodies that are “assumed ideal for haptic interaction” (Walters 176) and others that may be precluded from interaction altogether. This exclusion of certain persons and particular bodies from participatory experiences in the museum sits in sharp contrast to the lauded potential for the democratization of cultural experience that museologists see resulting from these experiences. While interactive technologies can be used, and are being used, to break down traditional barriers between the cultural elite of the institution and the lay visitor, they can, at the same time, create a new divide between those with the digital literacies and physical abilities needed to transcend those bounds through participation in certain rhetorical experiences and those without those literacies and abilities.

This potential division in access and cultural equity resulting from differences in digital literacies or physical ability is in no way deliberate on the part of the museum. On the contrary, as a public institution with free and open admission and a carefully designed set of tours and assistive technology devices for visitors who are visually impaired or hard of hearing, the Cleveland Museum of Art works diligently to provide broad and accessible engagement with their collection. Also, the entire Gallery One space, and the technology within it, was designed to make both the museum and the collection more accessible to a wide range of potential visitors. As I have shown, the Collection Wall not only succeeds in engaging visitors in a dynamic way, but goes far beyond that to make possible rhetorical experiences that persuade the visitor to take up more participatory and democratic roles than were previously available to them.

At the same time, as emerging technologies, particularly touch-screen interfaces, become more and more ubiquitous in our society, it can be easy to focus on the benefits seen in new and exciting uses of those interfaces and less on the interfaces themselves. Cynthia Selfe warned, in some of the first salient discussions of critical digital literacy, “Technologies may be the most profound when they disappear. But when this happens they also develop the most potential for being dangerous” (160). The potential for touchscreen and other emerging technologies to result in disparities of access, interaction and participation, reifies the necessity for continued examination into the habits and modes of interaction afforded by these technologies in spaces of cultural exhibition and display. As interactive interpretive technologies both evolve and become more commonplace, we must pay close attention not only to the interpretive positions certain rhetorical experiences persuade visitors to take up but also to who does and who does not perceive access to those relationships and the rhetorical experiences the interfaces that mediate them make possible.

- 1. Not to be confused with Teena Carnegie’s “modes of interactivity” (169) that she uses to describe engagement with new media interfaces. Interactive modalities in my case refer to the kinds of ways a user physically interacts with the touchscreen interface.

- 2. Visitors use iPads to access the ArtLens app, which syncs to the wall via RFID tag. Visitors who have their own iPads may request RFID stickers to adhere to their own device for that visit and future use. If a visitor wishes to use the ArtLens app in Gallery One and/or throughout the museum but does not have an iPad with them, they may rent one for the day. The ArtLens app was originally released for the iPad, but has since been made available for both iPhone and Android operating systems.

- 3. Visitors create tours on iPads with the ArtLens app. The ArtLens tour database is then synced with the Collection Walls at regular intervals.

Anderson, Gail, ed. Reinventing the Museum: The Evolving Conversation on the Paradigm Shift. 2nd ed. Lanham, MD: AltaMira P, 2011. Print.

Barrett, Jennifer. Museums and the Public Sphere. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011. Print.

Bowen, Lauren Marshall. “Resisting Age Bias in Digital Literacy Research.” College Composition and Communication 62.4 (2011): 586–607. Print.

Burke, Kenneth. A Rhetoric of Motives. Berkeley: U of California P, 1969. Print.

Carnegie, Teena A.M. “Interface as Exordium: The Rhetoric of Interactivity.” Computers & Composition 26.3 (2009): 164-173. Print.

Clark, Gregory. “Rhetorical Experience and the National Jazz Museum in Harlem.” Places of Public Memory: The Rhetoric of Museums and Memorials. Tuscaloosa: U of Alabama P, 2010. Print.

Cleveland Museum of Art. “Cleveland Museum of Art.” Text. Cleveland Museum of Art. 2016. Web. 5 June 2016.

Dewey, John. Art as Experience. New York: Pedigree Books, 1934. Print.

Farman, Jason. Mobile Interface Theory: Embodied Space and Locative Media. New York: Routledge, 2012.Print.

Fountain, T. Kenny. Rhetoric in the Flesh: Trained Vision, Technical Expertise, and the Gross Anatomy Lab. New York: Routledge, 2014. Print.

Gibson, James J. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1986. Print.

Haddon, Leslie, Enid Mante-Meijer, and Eugène Loos. Generational Use of New Media. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2012. Print.

Haskins, Ekaterina. “Between Archive and Participation: Public Memory in a Digital Age.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly 37.4 (2007): 401–422. Print.

Hayward, Vincent, Oliver R. Astley, Manuel Cruz-Hernandez, Danny Grant, and Gabriel Robles-De-La-Torre. “Haptic Interfaces and Devices.” Sensor Review 24.1 (2004): 16–29. Print.

Jones, Rodney H, and Christoph A Hafner. Understanding Digital Literacies: A Practical Introduction. New York: Routledge, 2012. Print.

Knobel, Michele, and Colin Lankshear. A New Literacies Sampler. New York: Peter Lang, 2007. Print.

Kress, Gunther R. Literacy in the New Media Age. New York: Routledge, 2003. Print.

Kress, Gunther R, and Theo Van Leeuwen. Multimodal Discourse: The Modes and Media of Contemporary Communication. New York: Arnold, 2001. Print.

Lee, Carmen K.M. “Affordances and Text-Making Practices in Online Instant Messaging.” Written Communication 24.3 (2007): 223–249. Print.

Luke, Timothy W. Museum Politics: Power Plays at the Exhibition. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2002. Print.

MultiTaction. “MultiTouch Delivers Europe’s Biggest Interactive Wall for Research Purposes.” MultiTaction Advanced Innovative Solutions. 2014. Web. 7 May 2014.

Parisi, David. “Fingerbombing, or ‘Touching Is Good’: The Cultural Construction of Technologized Touch.” The Senses and Society 3.3 (2008): 307-327. Print.

Parry, Ross. Recoding the Museum: Digital Heritage and the Technologies of Change. New York: Routledge, 2007. Print.

Paterson, Mark. The Senses of Touch: Haptics, Affects, and Technologies. Oxford; New York: Berg, 2007. Print.

Samis, Peter. “The Exploded Museum.” Reinventing the Museum: The Evolving Conversation on the Paradigm Shift. Ed. Gail Anderson. 2nd ed. Lanham, Md.: AltaMira Press, 2012. Print.

Sanders, John. Perspectives on Embodiment: The Intersections of Nature and Culture. New York: Routledge, 1999. Web. 5 June 2016.

Selfe, Cynthia L. Technology and Literacy in the Twenty-First Century: The Importance of Paying Attention. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois UP, 1999. Print.

Simon, Nina. “Principles of Participation.” Reinventing the Museum: The Evolving Conversation on the Paradigm Shift. Ed. Gail Anderson. 2nd ed. Lanham, Md.: AltaMira Press, 2012. Print.

Walters, Shannon. Rhetorical Touch: Disability, Identification, Haptics. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2014. Print.