Helen J Burgess, North Carolina State University

Roger Whitson, Washington State University

(Published November 18, 2019)

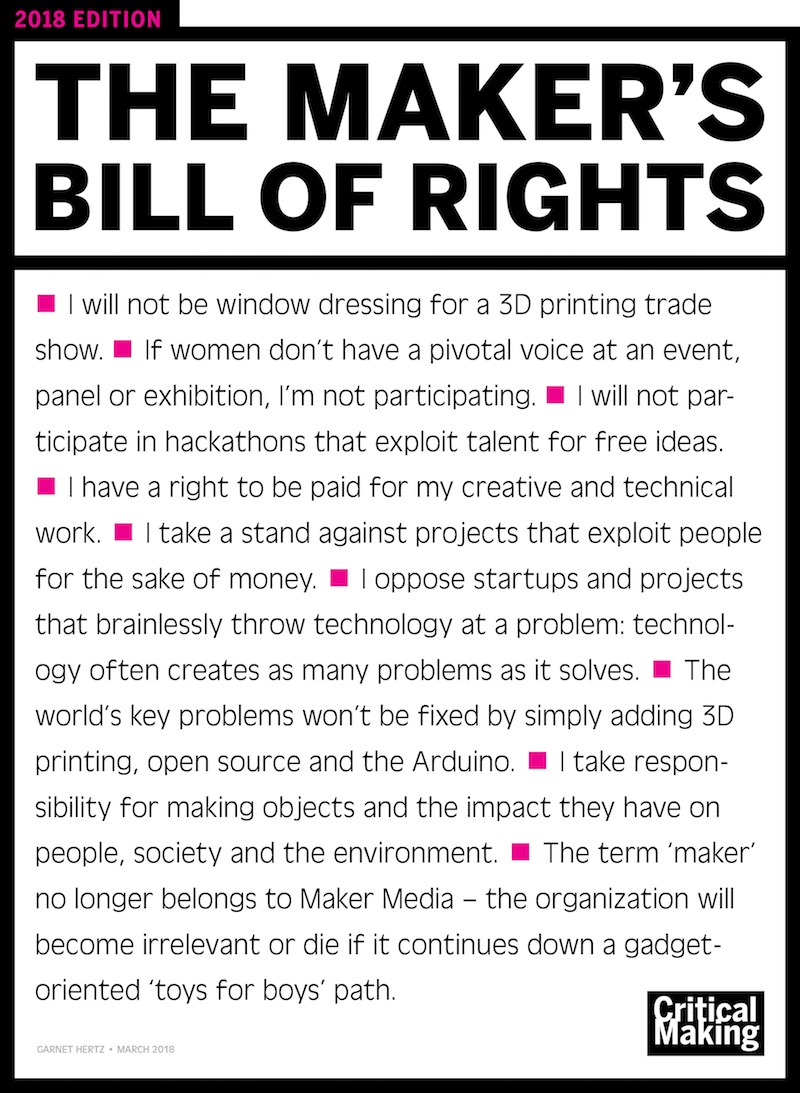

In the Summer 2018 issue of Neural magazine, DIY (“do-it-yourself”) and design scholar Garnet Hertz proclaimed that “We Need Something Better Than the Maker Movement.” Reminding us that the maker movement is a branding of “experimental electronic art and hacker practices,” he notes that the term was copyrighted in 2005 by Dale Dougherty, Make: magazine, and O’Reilly Media. To intervene in Make:’s growing monopoly of electronic art and hacker culture, Hertz created his own version of “The Maker Bill of Rights,” a sticker originally published by Make: in 2006 (see fig. 1).[1] The original sticker included such easily identifiable maker values as “[c]ases shall be easy to open” and “[p]ower from USB is good; power from proprietary power adapters is bad” (Hertz, “We Need”). By contrast, Hertz’s sticker focuses on the power imbalances that are part of maker culture: “[i]f women don’t have a pivotal voice at an event, panel or exhibition, I’m not participating;” “I have a right to be paid for my creative and technical work;” “I take a stand against projects that exploit people for the sake of money” (Hertz, “We Need”). In the introduction to Disobedient Electronics, while noting that “building electronic objects can be an effective form of social or political protest,” Hertz says that “the larger issues of what it means to be a human or a society needs to be directly confronted” (Disobedient 2).

Figure 1. Garnet Hertz’s “Maker’s Bill of Rights” sticker (Hertz “We Need”).

Of course, experimentation in fabrication and electronic art can be a powerful means of expression and resistance, yet the emphasis on “innovation” and “value” in maker culture continues to shift the focus away from tinkering and toward commodification. As Ashley Reed points out, the maker movement embraces a model of technological development in which “garage tinkerers and maker labs act as inexpensive research and development arms for major corporations” (28). Given the loss of state funding, the rise of precarity on university campuses, and the loss of prestige among humanities departments, university makerspaces promise the same kind of cheap innovation for desperate administrators and faculty. As an example, Satish Subramanian notes in a 2017 article that universities are “tapping into their student population’s ‘maker’ spirit” by “investing in new spaces, curricula and partnerships to transform libraries into new-age spaces for exploration and innovation” (Subramanian). In the spirit of contesting such monetized articulations of the maker movement, this issue looks to hacker and electronic art practices as work that can be done both within and without makerspaces—in acts that resist the constant pressure for innovation, commodification, and planned obsolescence that have become a hallmark for technological development under late capitalism.

When Helen J. Burgess and David M. Rieder celebrated the “scholarship-as-making” DIY culture found in their Hyperrhiz issue “Kits, Plans, and Schematics,” they recognized the need for experiments in what they called “executable culture": that is “cultural objects that can be shared widely and downloaded for execution (building / rebuilding) as physical objects at the other end of the network” (Rieder, “Introduction”). Drawing from the genre conventions of such sites as Instructables as well as the burgeoning popularity of Make:, “Kits, Plans, and Schematics” provides a scholarly framework for reproducible and transmittable forms of DIY expression. “Critical Making and Executable Kits” adds a focus on critical making, coined by Matt Ratto as “acts of making,” which “through the sharing of results and ongoing critical analysis of materials, designs, constraints, and outcomes [ . . . ] perform[s] a practice-based engagement with pragmatic and theoretical issues” (253). Jessica Barness and Amy Papaelias add that critical making “places emphasis on the making process itself” and this focus on process “may produce as much knowledge as the polished, finished product” (6). As such, our issue places special focus on sharing and the various processes involved in the construction of objects and knowledge—aligning it with similar projects in the digital humanities, digital rhetoric, design, and computers and writing like Jentery Sayers’s “prototyping," Rita Raley’s “tactical media,” David Michael Sheridan’s “3D rhetoric,” Michael Farris et al.’s “maker rhetoric,” Phoebe Sengers’s “critical technical practice,” David M. Rieder’s “suasive iterations,” Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby’s “speculative design,” and Carl DiSalvo’s “adversarial design.”[2]

For us, the focus on process and critical inquiry in critical making adds a crucial component to understanding the projects of executable culture explored in both the Hyperrhiz issue and in this one: namely, the ability to focus on various kinds of executable processes and their critical frameworks. As Hertz elaborates in his handmade zine project Critical Making, “hands-on physical work has a clear place in enhancing and extending the process of critical reflection” (4). To what degree can scholarly communication enact Hertz's "critical reflection" while describing executable processes of making, or exploring alternate configurations for the devices executed by their plans? Such a focus on alternate histories, processes, and configurations of object-work critiques the notion that any one process inevitably leads to the best version of an executable project, while also recalling media archaeology’s critique of what Jussi Parikka calls “a hegemonic linearity that demands that we should see time and history as straight lines that work towards improvement” (12). As an alternate vision to what the maker movement sees as “innovation,” we present a series of material engagements with executable culture—all of which focus on the processes of critical making to explore what technology does to our sense of humanity and social life.

This special issue of enculturation, “Critical Making and Executable Kits,” provides a broad sampling of projects in a range of disciplinary and interdisciplinary valences for educators, researchers, and artists to embrace kits and schematics without appropriating the monopolistic practices of maker media. In the process, we unite scholars in the digital humanities, digital rhetoric, creative writing, and computers and writing to construct a “kit of kits” that showcases a range of approaches to making, sharing, and thinking with things. Extending “critical making” as a term, we can see formulations long rooted in composition studies, rhetoric, and technical communication studies that resonate with the core premise of using objects to think through and express complex issues. Gunther Kress’ work in multimodality and pedagogy immediately springs to mind, as does Jody Shipka’s formulation of a “composition made whole” that incorporates elements “including, but not limited to, the digital.” (“Including” 73). David M. Rieder’s work in Suasive Iterations rethinks working with electronic components and physical computing as a way “to transduce physical energy” from one form to another in such a way that physical computing spaces become “suasive” (12). From the perspective of technical communication, we can reframe making in terms of what Liza Potts calls “experience architecture”: “an emerging practice, one that draws together issues of information design, information architecture, interaction design, and usability studies to assess and build products, services, and processes” (256). While Potts has in mind interface design of the kind we see in digital humanities, we could easily extend this term to encompass the kind of work Dawn Opel and John Monberg engage in in this collection: building kits of resources with which to navigate and reflect upon the kinds of experiences we have with/in the healthcare community. Ann Shivers-McNair’s kit in this collection offers a user’s guide to embodied methods for approaching making: paying careful attention to the materials and strategies we employ when conducting studies of how, where and why communities “make.”

The role of bodies and the way they move through and manipulate the world cannot be overstated in this collection—in particular, in reading back over the essays we were surprised by the prominent role hands play as they assemble, rearrange, and signify in front of and behind the screen. Nancy Tuana’s observation that “[k]nowledge arises from the flesh—that intertwining of my body and the world, and my interactions with others” (236) resonates with the movement of hands as they assemble an artist’s book in Amaranth Borsuk’s “The Abra Codex” kit, or the hands of a rhetor, carefully positioning fingers, elbows and hips in the gestural forms of “Supplico” and “Gestus II” in Steven Smith’s kit for creating a “Digital Chironomia.” Helen J. Burgess, Krystin Gollihue, and Stacey Pigg focus on the movement of fingers through fiber as the original digital technology—what Angela M. Haas points to as “our fingers, our digits, one of the primary ways . . . through which we make sense of the world and with which we write into the world” (84)—while Nina Belojevic advocates for “reading videogames with your hands.” Moving away from fingers, Jason Lajoie’s “muscle developer” seeks to unmake our traditional conception of the masculine body, while Jessica Schriver provides a template for rethinking what it means to be a “mother.” Chris Justice looks at the way our bodies move through the world, leaving a trail of detritus and “waste” that can be reconfigured; Marcel O’Gorman and Roger Whitson call our attention to the emptiness of our senses and mindfulness of our place in the world.

Much work remains to be done, of course, and this collection is merely a starting point, as all kits and plans must be. One of the ongoing points of tension in studying “making” is its inevitable and uneasy relationship with histories of colonization and ownership—the “hacker ethic” being a close ally of remix and practices of creative appropriation. Following Adam Banks’ injunction against “build[ing] our theorizing on individual practices without full recognition of the people, networks, and traditions that have made these practices their gift to the broader culture” (13), one should always ask in the context of critical making: whose hands are doing the making? Where did these materials come from? Who made them? What happens to them after they are discarded? How can we amplify or acknowledge those previous makers’ work in a way that cares for all participants? More generally, we seek to understand, as Margaret Konkol puts it, cultural artifacts as “embedded in complex systems of labor, exchange, and waste” (3).

With the caveats above, and acknowledging our own privileged place in this process, we present this kit of prototypes and plans as a way of enacting design, rhetoric, and hacking in the world: as a call to action. All the kits’ authors invite the reader, user, and maker to adapt the work for their own purposes—to create a tackle cache for thinking about waste and fisheries, to create a motion-capture apparatus for exploring traditional gesture as a mode of delivery, to make a basket, or to disassemble a videogame. Download the code, adapt the templates, add in (or throw out) what is needed or missing. Or just (but not merely) sit still for a moment, and think about what we’re doing.

What’s in the Box?

Glitches and Books

The first section of projects includes three works that use critical making to rethink how we engage with materials and media.

Nina Belojevic’s “A Glitch Taxonomy Kit, or How to Read Videogames with Your Hands” uses circuit bending to study the material elements of the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). Circuit bending involves exposing the circuit boards of any electronic device, then probing for potential electrical connections between the circuits—called bends—to produce effects that were never intended by the manufacturer of the device. Belojevic uses this method to create a “glitched” Nintendo console, then provides a taxonomy of the glitch effects she experienced. By including instructions for readers to create their own kits, she encourages readers to compare the graphic, sonic, and temporal interventions produced by their glitched console with the ones she created.

Amarath Borsuk’s “The Abra Codex” kit features instructions for people to make a born-digital artist book based upon the installation she created with Kate Durbin and Ian Hatcher. Consisting of a limited-edition handmade book and an iOS app, The Abra Codex uses touchscreens and animation to test the haptic dimensions of book history. In the kit, Borsuk includes a so-called “open edition” produced as an executable version of the handmade edition she produced for the installation. The result is that readers are able to create their own editions of The Abra Codex to interface with the iOS app—testing the boundary between notions of uniqueness found in limited-edition books and the standardized experiences found in ebooks and computer files. By moving from the material of the book to the screen of the smartphone application, Borsuk encourages reading as a participatory act of transforming the materiality of the book with our hands.

Steven Smith’s “The Digital Chironomia” explores how gestural technologies like the Xbox Kinect and TouchDesigner can reinvigorate discussions about the role of gesture in rhetorical delivery. Smith uses gestural software to archive various habitual gestures illustrated in Gilbert Austin’s Chironomia, or A Treatise on Rhetorical Delivery and John Bulwar’s Chirologia, Or the Natural Language of the Hand (1644). Such an approach invites us to recenter the canon of delivery as a way of approaching the interaction between our bodies and digital-imaging technologies.

Entanglements

Kits in this section offer opportunities to reflect on the ways our bodies interact with and are entangled in the physical world as producers of textiles, tools, and trash.

Helen J. Burgess, Krystin Gollihue, and Stacey Pigg’s “The Fates of Things” offers a performative intervention into thinking about the kinds of crafting usually accounted for as “women’s work.” Taking on the forms of the classical Fates, Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos, the authors deploy embedded accelerometers to produce remixed texts from data captured while spinning, weaving, and printing textile objects.

Christopher Justice’s “The Tackle Cache” explores the fisher’s tackle box as a site of memory and storytelling. Addressing the ecological impact of trash in fisheries, Justice explores the mnemonic impact of such objects to anglers and the fishing stories they tell. Caches are left by a body of water, with instructions for the passers-by to leave objects and memories. Objects tell their own stories, and Justice also shows how tackle caches can be used in writing exercises to engage students in an exploration of collecting and discarding.

Bodies and Configurations

Kits in this section invite the reader to explore the de/construction of gender performance.

Jason Lajoie’s “Critically Unmaking the Culture of Masculinity” recreates William Bankier’s “muscle developer” including an accelerometer, a microcontroller, an LED screen, and a small novelty shock pen. Every time a user exercises their biceps, they receive a small shock to their muscles. The developer mirrors Bankier’s belief that maximum development of the muscles involves a combination of exercise and electrical stimulation. Lajoie uses this object to show how masculinity in turn-of-the-century America traded upon notions of technique and electrical technology to perform mastery over the body. Apart from its resonances in earlier nineteenth-century literature, Luigi Galvani’s experiments using electricity to make the legs of frogs twitch is referenced in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; Lajoie’s work also uncovers how microprocessors and maker culture participate in the cultural techniques of masculine bodies.

Jessica Schriver’s “Prosthetic Womb Kit” is a design fiction—what Julian Bleecker has described as objects that are “component parts for different kinds of near future worlds” (7). The project combines feminist activism with body modification, disability and transgender studies, and posthumanism—particularly as these ideas are explored in Katherine Dunn’s novel Geek Love. Schriver sees the womb as an alternative to the various drug recipes the characters Lil and Al used to become pregnant in the novel. Schriver includes instructions on how to make a “prosthetic womb doll,” featuring instructions for de-naturalizing the female body and engaging with the womb as a cybernetic apparatus.

Experience Architecture

The kits in this section offer guidelines and templates for conducting research and mapping experiences.

Dawn S. Opel and John Monberg’s “Mapping the Network of the Cancer Clinical Trial: A Toolkit for Health Equity Activism” maps the complexity of doctor and patient relationships in cancer clinical-trial treatment. Opel and Monberg use the latter’s own experience navigating a frontline clinical trial for a drug to treat Mantle Cell Lymphoma as a model for understanding situational mapping and how knowledge producers in the health industry espouse opinions that are situated, networked, and perspectival. Their toolkit includes a sample journey map, used to chart a patient’s path through doctors and resources; a video transcript of a talk on situational mapping, the major methodology leading patients through the complexities of cancer decision-making; and a set of guiding questions readers can use in their own journey maps.

Ann Shivers-McNair’s “Making Knowledge: A Kit for Researching 3D Rhetorics” investigates 3D interviewing as “an accountable methodology and method for 3D rhetorics research” developed from qualitative research traditions. She provides a comprehensive discussion of tools and strategies for conducting 3D interviews, foregrounding the responsibility we have as researchers to acknowledge our entanglement in complex technological and social networks.

Sitting Still

Finally, the two kits in this section offer lessons in slow rhetoric, asking us to reflect on the meditative affordances of our interactions with technology.

Marcel O’Gorman’s “A Smartphone Basket to Make Media Theory” draws on “Basketcase,” a domestic craft work designed by Caitlin Woodcock. Referencing the work of Robin Wall Kimmerer in Braiding Sweetgrass, O’Gorman grounds his discussion of domestic craft in an alternative history of technology that re-centers “making as morphogenesis”—that is, making as a “mutual involvement of people and materials in an environment” (Ingold, 346).

Roger Whitson’s “Now: A Kit for Digital Mindfulness” presents a series of meditations that compare experiences with technology and time found in mindfulness practice with media-archaeological accounts of time-criticality. In addition to traditional Buddhist practice, mindfulness includes what Mikey Siegel calls “consciousness hacking,” in which the mind and consciousness are seen as kits that can be altered using various phenomenological processes.[3] Conceptualized as a series of exercises, Whitson shows how visualization and emptiness practices can transform the anxiety associated with asynchronous conversations on social media into a critical framework for exploring the near-instantaneous microtemporal pulses flowing through our technological devices and the unimaginably long macrotemporal epochs forming the components making up those devices.

[1] On June 8, 2019, Tech Crunch reported that “[f]inancial troubles have forced Maker Media, the company behind crafting publication MAKE: magazine as well as the science and art festival Maker Faire, to lay off its entire staff of 22 and pause all operations.” Crunch reporter Josh Constine noted that after a GoFundMe page dedicated to resurrecting the troubled company appeared and Oculus co-founder Palmer Luckey stated an interest in funding Make:, Dale Dougherty announced that licensed Maker Faire events could continue as planned. Still, it isn’t clear what future Maker Media has, nor does its hold over the branding of creative electronic or craft projects seem secure. A day after the announcement Hertz created a Google Form called “After Make” inviting scholars to imagine the future of “open source maker-oriented projects.”

[2] For discussions of each of these projects see Jentery Sayers, “Prototyping the Past”; Rita Raley, Tactical Media; David Michael Sheridan, “Fabricating Consent: Three-Dimensional Objects as Rhetorical Compositions”; Michael Faris et al., “Building Rhetoric One Bit at a Time: A Case of Maker Rhetoric with Little Bits”; Vera Khovanskaya et al., “The Case of the Strangerationist: Re-interpreting Critical Technical Practice”; David M. Rieder, Suasive Iterations: Rhetoric, Writing, and Physical Computing; Anthony Dunne, Speculate Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming; Kari Kraus, “Finding Faultines: An Approach to Speculative Design”; and Carl DiSalvo, Adversarial Design.

[3] Kevin Gray interviews Siegel and his group in “Inside Silicon Valley’s New Non-Religion: Consciousness Hacking.”

Banks, Adam J. Digital Griots: African American Rhetoric in a Multimedia Age. Southern Illinois UP, 2011.

Barness, Jessica, and Amy Papaelias. “Critical Making at the Edges.” Critical Making: Design and the Digital Humanities, special issue of Visible Language, edited by Jessica Barness and Amy Papaelias, vol. 49, no. 3, Dec. 2015, pp. 4-11.

Bleecker, Julian. Design Fiction: A Short Essay on Design, Science, Fact and Fiction. Near Future Laboratory, Mar. 2009. https://drbfw5wfjlxon.cloudfront.net/writing/DesignFiction_WebEdition.pdf

Constine, Josh. “Maker Faire Halts Operation and Lays Off All Staff.” Tech Crunch, 9 June 2019. https://techcrunch.com/2019/06/07/make-magazine-maker-media-layoffs/.

DiSalvo, Carl. Adversarial Design. MIT P, 2015.

Dunne, Katherine. Geek Love. Alfred A. Knopf, 1989.

Dunne, Anthony and Fiona Raby. Speculate Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. MIT P, 2013.

Faris, Michael J., et al. “Building Rhetoric One Bit at a Time: A Case of Maker Rhetoric with LittleBits.” Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, vol. 22, no. 2, Spring 2018.

Gray, Kevin. “Inside Silicon Valley’s New Non-Religion: Consciousness Hacking.” Wired, 1 Nov. 2017. https://www.wired.co.uk/article/consciousness-hacking-silicon-valley-enlightenment-brain

Haas, Angela M. “Wampum as Hypertext: An American Indian Intellectual Tradition of Multimedia Theory and Practice” Studies in American Indian Literatures, vol. 19, no. 4, Winter 2007, pp. 77-100.

Hertz, Garnet. “Open Source ‘After Make ‘ Ideas” Google Forms. https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSdILip2RMZ7EwY0UMxThvi7XblGcREahpppL1zj8tgSPeN4gQ/viewform

---.“Introduction.” Disobedient Electronics: Protest, edited by Garnet Hertz. The Studio of Critical Making, 2018. pp. 1.

---. “Making Critical Making.” Critical Making, edited by Garnet Hertz. Telharmonium P, 2012. pp. 1-10.

---. “We Need Something Better Than the Maker Movement.” Neural, no. 60, Spring 2018.

Ingold, Tim. The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. Routledge, 2000.

Khovanskaya, Vera, et al. “The Case of the Strangerationist: Re-interpreting Critical Technical Practice.” Proceedings of the 2016 ACM Conference on Designing Interactive Systems, pp. 134-45.

Kraus, Kari. “Finding Fault Lines: An Approach to Speculative Design.” The Routledge Companion to Media Studies and Digital Humanities, edited by Jentery Sayers. Routledge, 2018, pp. 162-73.

Kress, Gunther. Multimodality: A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication. Routledge, 1970.

Konkol, Margaret. “Prototyping Mina Loy’s Alphabet.” Special Cluster: Feminist Modernist Digital Humanities, special issue of Feminist Modernist Studies, edited by Amanda Golden and Cassandra Laity, vol. 1, no. 3, 2018, pp. 294-317.

Parikka, Jussi. What Is Media Archaeology? Polity, 2012.

Potts, Liza. “Archive Experiences: A Vision for User-Centered Design in the Digital Humanities.” Rhetoric and the Digital Humanities, edited by Jim Ridolfo and William Hart-Davidson. U of Chicago P, 2015. pp. 255-263.

Raley, Rita. Tactical Media. U of Minnesota P, 2009.

Ratto, Matt. “Critical Making: Conceptual and Material Studies in Technology and Life.” The Information Society, vol. 27, no. 4, 2011, pp. 252-260.

Reed, Ashley. “Craft and Care: The Maker Movement, Catherine Blake, and the Digital Humanities.” Essays in Romanticism, vol. 23, no. 1, Spring 2016, pp.

Rieder, David M. “Introduction.” Kits, Plans, Schematics, special issue of Hyperrhiz: New Media Cultures, edited by Helen J Burgess and David M. Rieder, vol. 13, Fall 2015. doi:10.20415/hyp/013.i01.

---. Suasive Iterations: Rhetoric, Writing, & Physical Computing. Parlor, 2017.

Sayers, Jentery. “Prototyping the Past.” Visible Language: The Journal of Visual Communication Research, vol. 49, no. 3, Dec. 2015, pp. 157-77.

Shelley, Mary. Frankenstein, Or The Modern Prometheus. 3rd ed., edited by D.L. MacDonald and Kathleen Sherf. Broadview P, 2012.

Sheridan, David Michael, “Fabricating Consent: Three-Dimensional Objects as Rhetorical Compositions.” Computers and Composition, vol 27, no. 4, Dec, 2010, pp. 249-65.

Shipka, Jody. “Including, but Not Limited to, the Digital: Composing Multimodal Texts.” Multimodal Literacies and Emerging Genres, edited by Tracy Bowen and Carl Whithaus, Pittsburgh: U of Pittsburgh P, 2013. pp. 73-89.

---. Toward a Composition Made Whole. U of Pittsburgh P, 2011.

Subramanian, Satish. “Futurizing the Stacks: How Makerspaces Can Modernize College Libraries.” EdSurge, 30 Sept, 2017. https://www.edsurge.com/news/2017-09-30-futurizing-the-stacks-how-makerspaces-can-modernize-college-libraries.

Tuana, Nancy. “Material Locations: An Interactionist Alternative to Realism/Social Constuctivism.” Engendering Rationalities, edited by Nancy Tuana and Sandi Morgen, SUNY P, 2001. pp. 221-243.