Carmen Kynard, Texas Christian University

(Published March 24, 2022)

Long before vocabulary like “cultural appropriation” became commonplace for the everyday race-talk of even the minimally informed, I was clear that Black youth creativity set the terms for bodily syntax across the globe. By 21 years old, I lived in what I will call a state of meta-Black-visual-awareness. Here’s an example. Somewhere circa 1992, I wore my denim pants backwards in homage to the style of the youngest Hip Hop duo to achieve gold and platinum albums: 12-year-old Chris Smith and 13-year-old Chris Kelly (R.I.P.), who together formed the sensation known as Kris Kross. It was an experience that I will never forget because of the sheer discomfort of a metal zipper riding up my backside with no stretch, give, or back pockets, especially when I sat down. I was stunned by how many people were rolling with their pants like this and yet they did so for one reason: Black youth made it look good (make ya jump jump). As I watched other young, Black people like myself, I remember looking down at my own body with a clear realization: when it comes to style, embodiment, and visuality, young Black people will literally make you hurt yourself riding out with your pants on backwards; they start it, and the world follows. Whether we are talking about the seriousness of sneaker culture, the changes in basketball uniforms (down to the colors of the socks), the uptick in goose-down bubble coats for everyday winter wear (formerly only worn by white ski-vacationers), the best ways to shape up and look in a fitted cap or taper fade, the revised uses of phone technologies (from pagers to mobile phones), or the fool-proof strategies to beat your face/eyebrows/weave/earrings, we are talking about Black visual cultures that are inherently and actively interrupting the daily aesthetic dominance of whiteness. Black youth culture, Hip Hop, and Black resistance are at the core of these interruptions, no matter how much co-opting, colonization, and outright theft that Black creativity experiences.

Inspired by the aesthetic philosophies of Black youth, my purpose in this essay is to explore Black visuality as a central component of Black Digital rhetoric, Black aesthetic culture (on and offline), and Black feminist pedagogies in classrooms, especially in the context of Black national protest and political eruptions. I inform my thinking most critically with the work of Black scholars who examine photography, paintings, and sculpture—scholars like Richard Powell, Kellie Jones, Deborah Willis, Brian Wallis, Charmaine Nelson, Nicole Fleetwood, Krista Thompson, and Tina Campt— to push past the alphabetic/verbal obsessions of even digital rhetoric that can often disembody the raced visuality of digital messaging. I see these scholars’ thinking on Black visuality far beyond the confines of art history or art criticism. These fields examining Black art-historical and visual culture are not limited to Blackness as exhibited and sanctioned by white-controlled art institutions. Without such theorists, we run the risk of framing visual rhetoric/digital rhetoric in hopelessly whitened ways when the visual cultures in which we live have always been deeply racialized and decidedly anti-Black (Wallace). I intend instead to see radical Blackness as an active, everyday/all-day visuality that informs classrooms and digital pedagogies in the Movement for Black Lives (M4BL) in ways that explode what we imagine as digital rhetoric in the academy and out. I am particularly using the umbrella terms M4BL in the way that Barbara Ransby does, a historian of Black women’s activism and an activist herself in Chicago, in encompassing Black Lives Matter in its original political impulse based on the vision of its founders, Opal Tometti, Alicia Garza, and Patrisse Cullors Khan and organizations like the BYP100 and the Dream Defenders. Understanding the M4BL this way and centering this particular arc of activists means seeing this moment as one which has been fundamentally shaped by Black feminists/ Black queer feminists/ Black gender-nonconforming folk/ Black trans folk who have been more deliberately intersectional than in any Black social movement we have seen (Cohen and Jackson).

Black Visuality as Refuge, Uprising, and Pedagogical Commitment

Black visuality as a pedagogical commitment, especially in digitized communications, is easy enough to theoretically achieve. However, hitting this as an everyday classroom praxis has taken some real doing for me. I have to actively disrupt aesthetic whiteness, white alphabetic obsession, white affect, and institutional whiteness all at the same time. I try to use every visual moment to do so, even if I fail. In one fall semester where I brilliantly failed, I bought this really fly (or so I thought) basket with handles that was crafted by Ghanaian women. My students loved the woven designs as much as I did. However, they were just beside themselves when it came to the way I decided to use the basket: as a purse. I mean, why not? The colors were just EVERYTHING and were just my style. In all fairness, I didn’t use the basket simply as a purse. I used it as a schoolbag to carry supplies and such from home and to the classroom. Well, this was the final straw, literally. As a Black Diasporic community, my college students explained with a quickness that their grandmothers in Africa and the Caribbean used such baskets/bags in their rural communities across the world to carry fish, vegetables, and fruits from the market, not schoolwork. Apparently, classroom projects, fish, and vegetables should not cross-contaminate especially for someone in my age category. I ignored them and carried that bag until it came apart because I looked good carrying stuff like that no matter what they said. My point here is that I don’t direct Black students’ designs since they clearly do not need me for that or ever even agree with my self-proclaimed flyness. They don’t have to since they have their own ideas about how the Black visuality which nurtures them can be mobilized to reimagine their design, work, and lives. My job is to remind them that they have their own visual histories and traditions and to think with and through them as they compose every aspect of their college learning and life, especially online.

The sheer supra-competence of the visual design work of Black college students has deeply inspired me. Although I obviously never only teach Black students, a Black feminist political philosophy still shapes how I frame pedagogical and literate possibilities in my classrooms (Kynard, 2018). I reject the hopelessly compromised strategy of trying to convince privileged white students of their important social roles in combatting racism and white privilege, a mechanism that centers whiteness and white youth’s (mis)understanding which also forces Black teachers to capitulate to a white assimilationist pedagogy. As Sadiya Hartman (2003) reminds us, “so much of our political vocabulary/imaginary/desires have been implicitly integrationist even when we imagine our claims are more radical… and particularly when [integration into the national project] is in crisis, black people are called upon to affirm it” (185). Inclusion and/or integration always happen within a specified and “limited set of possibilities” alongside an “inexorable investment in certain notions of the subject” (185). As Sylvia Wynter’s body of work contends, Blackness is an altogether different subject position and, once inserted into any theoretical paradigm, pulls at its white frays and brilliantly unravels it, the exact opposite of an inclusion/integration ethos (McKittrick, 2013). Blackness, then, is THE analytic. While I certainly understand that I have been made Black within the specific and violent terms of western social constructions of slavery, I also stay Black in service to the ancestral forces that have uniquely textured the ways that I understand, analyze, live, love, and remake the world in the wake of slavery (Sharpe). It is precisely at this level of the Black analytic that the white academy and white scholars sink into their ongoing confusion though. When I am asked, for instance, over and over and over again, what I do differently when I am teaching white students, my answer continues to baffle folk when the answer should be obvious: I stay Black.

I make no apologies for pedagogical Blackness, especially when it comes to approaches to visual rhetorics, because Blackness as a pedagogy is always a theoretical interruption and alternative invention. This is not to say that I don’t encounter resistance from even Black students, but that resistance always looks different. Take for instance, Tanisha, who was convinced she was not creative enough to do the work that I was asking of her class and raised her hand to announce this fact rather boldly. To her astonishment, I started cracking up, real gut-wrenching laughter too. When I first met Tanisha, I thought she was a die-hard New York Knicks fan – always a strong possibility given that this urban, public college in New York City was only 20 blocks away from where the Knicks play. I was wrong. Tanisha liked the Knicks well-enough, at times, but what she really liked were the team’s colors royal blue and bright orange and when combined, all the better. I mean she adorned these colors everywhere: sneakers, pens, pencil cases, nails, shirts, earrings, erasers, bookbag, compact stapler, key chain. It was a daily ensemble for her, and it was very fly. When I finally stopped laughing, I told her that she sees creativity every time she looks up in the mirror or down at her nails. Pointing to her, I said: “girl, all you gotta do is all that right there!” And ALL THAT is exactly what she did. Her self-designed webspace for the course featured stunning black and white photo images of Black women outlined in orange and blue. The alphabetic text, videos, and other embedded images seemed to be suspended within the photo collage where her writing, in black words on a gray translucent background, was punctured with accented titles and phrases in orange and blue.

In the case of Tanisha’s final digital project, her body adornments, focus on Black topics, and web design all formed an obviously deliberate statement. When you saw all that orange and blue on top of Black, you just knew it was Tanisha’s work. I am suggesting something beyond just the literal here though. The body that Tanisha adorned daily is a body narrative that she writes everywhere (Ford). The self-styling that Tanisha pursues is deeper and bigger than merely wardrobe choices though; it is a deliberate, daily process toward her own self-assured Black visuality and forces us to expand our notions of visual rhetoric in ways that marry everyday Black stylings. The body narrative that Tanisha composes both online and in person engages Blackness in ways that conceptualize new possibilities for our thinking when we follow how she is re-imaging and thereby re-doing the realities of race, the politics of vision, and the daily relevance of the Black aesthetic. I think of Tanisha’s body narrative as Black vernacular creativity that communicates positionality and resistance as a kind of counter-cultural embodiment (even when Black women/Black girls/Black femme styles are white-coopted and un-credited, as seemingly everything always is, that doesn’t change their counter-cultural origins). Black vernacular creativity is also a visual language and exists as a metaphysical condition schooling may never completely comprehend, including and especially the fields related to rhetorical education.

Black Visuality…What It Be Like/What It Look Like/What It Do

In this essay, I am tasking myself with feeling and seeing the metaphysical reality of Black visuality. I spend considerable time quite literally re-looking at a set of Black students’ digital artifacts in my classes. I see their work in the way that Alexandra Lockett describes: as a temporal and spatial reality that disrupts “white hegemony by communicating in Black cultural codes” (168). I also see students’ work as a kind of activism and political resurgence that allows us to push past merely understanding current Black protest in the M4BL as macro, highly visible, and large-scale political struggles and activists. Sarah Hunt and Cindy Holmes—two cisgender queer women, one of whom is Indigenous and one of whom is a white settler—push my thinking with their contention that daily actions are as vital to decolonial processes as large-scale protests because they renew peoplehood and community resurgence and, in fact, give the courage and spirit to mass scale movements. Hunt and Holmes encourage us to move broadly past jurisprudence and past what Eve Tuck has so aptly called “damage-centered research”: appeals for white/hegemonic attention to marginalization by presenting communities of color as one-dimensional stock characters of brokenness, ruin, and depletion. Instead, I observe conscious and critical Black students’ digital projects as re-imaginations and re-assertions of the M4BL that emphasize the intimate, lived experiences of Black people’s struggles over the rhetorical projects of schooling under colonization.

I borrow deeply from scholarship and activism related to the role of Black art history, the struggles in decolonizing museum struggles, the politics of Black digital rhetoric, and the commitment to Black fugitivity. In doing so, my vocabulary centers these sets of interlocking but different terms:

Black A/art (Big A vs. little a): When I say Black Art (Big A), I am referencing an institutional definition in relation to the work shown in public museums via grants, endowments, etc. Black art (little A) references a counter-institutional definition in relation to the work bartered, viewed, sold, made, exchanged amongst Black people in their private and/or counter-public lives (i.e., at Black bookstores, African street festivals, etc). This also references the Black art historians who make their own Black identities and experiences a central transactional factor in their work.

Black daily aesthetic life/ Black visual culture/ Black visuality: These are the daily practices and undergirding histories/philosophies where multiple Black expressions inform everyday life including, but not limited to, natural hair/cornrows, music, fashion, home decor, gardening, nail design, quilting, or sewing.

Black vernacular creativity: I use this term to reference the Black counter-cultural and counter-public imaginations that are called up in discussions related to Black popular culture (Elam and Jackson, Haymes, Neal). I am doing two deliberate things here. First, I am pushing past the notion of vernacular as a negative slur to stand in for “dialect” especially since I mean something beyond the morphosyntactic structures of spoken or written language and something more akin to the deliberate, wider acts of cultural creation and making. Second, I am eschewing the notion of a “Black popular culture” as this is a redundancy since popular culture is, in fact, an amalgamation of Black counter-cultures that have been whitestreamed and diluted from the contexts in which their expressions were born.

Figure 1: Black Visual Rhetoric & the Movement for Black Lives--- An Overview

Black Digital-Cultural Imagination… What It Be Like/ What It Look Like/ What It Do

The students whose digital spaces I will examine here were all Black students in my general education college classes at an urban “Minority-Serving Institution” (MSI). Each course where I meet students is taught from a writing-and-multimodal-intensive pedagogy where every set of weekly reading assignments are accompanied by multi-genred composing tasks. At the end of the semester for every course that I teach, students collect and curate their own projects from the semester and design a digital space (which we learn to do together in a computer lab). They choose their projects and how to present them; they also decide if and when they will open their websites to public audiences and be google-searchable. I see these young Black people as digital authors who are composing their lives and alternative uses of digital communication with as much authority and competence as any academic or published author, and sometimes more so.

In the context of this article, I will focus on a platform that many universities had purchased at the time where students could customize the CSS in order to create the webspace that they wanted. I am especially interested here in how Black students push the limits of such university technologies—a structural system they are often excluded from—towards new innovations that explode these systems with Black digital creativity, thereby transforming technical interfaces and their usability (Brock). Towards that end, I introduce the platform’s small bit of CSS as yet another language for them to turn up on. In the context of this particularly corporate university platform, the CODE/CSS looks like this:

body {

background:#EEEEEE;

color: #222222;

}

#site_topnav ul li a {

color:#000000;

}

#header_container {

padding-bottom:0.5em;

padding-top:10px;

}

#header_container, #main_container {

background-color:#FFFFFF;

border-color:#FFFFFF;

border-style:solid;

border-width:0 10px;

position:relative;

}

#header_container .title {

border-bottom:2px solid #CCCCCC !important;

padding:15px;

}

#module_topnav{

border: 1px solid #ccc

}

.navigation_topnav {

background-color:#f7f7f7;

}

.navigation_topnav a {

color:#222222;

font-family: Verdana,Helvetica,Arial,sans-serif;

}

#footer_container {

background:none;

border-top:1px solid #AAAAAA;

}

.title{

display:block;

}

#footer {

background:none;

}

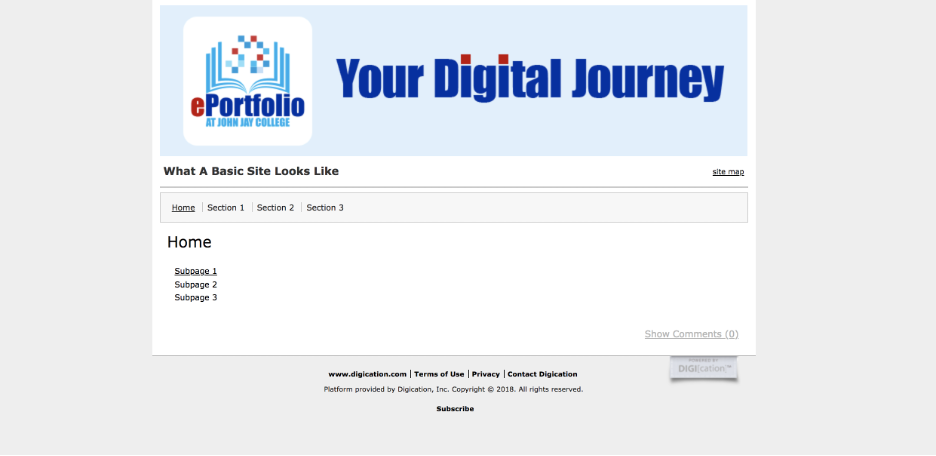

In its visual form, the code looks like this:

Figure 2: Default Look of University Platform for Corporate ePortfolios

Students have worked the limits of this code and visual envelope and have created what I call the Black Digital-Cultural Imagination. The slideshow below (that is also hyperlinked) offers a lens into how multiple students transformed the CSS to create Black space:

Figure 3: Black Digital-Cultural Imagination… PART I

After encountering dozens upon dozens of such digital designs by Black students, I was clear that some deep stuff was going down. Nicole Fleetwood’s analyses of Black artists and performers seem most apt: namely that these students are Black culture producers who mobilize visuality to render Black life visible, intelligible, and valuable in the ways that Fleetwood describes Black photographers like Teenie Harris. These are designers and curators who offer an alternative visual (and virtual) index of everyday Black life and thought. As Black cultural workers, these students are actively crafting Black visual landscapes where the white imagination of Blackness—spectacle, detriment, criminality, and commodifiability—are re-appropriated. As countervisual narratives, they are remaking representation and crafting representational spaces for figuring Black subjects and, as such, ignite new subject formation and knowledge production (Thompson).

These realizations of the power of Black visuality in my classrooms meant a personal re-training away from alphabetic analyses and obsession with students morphosyntactic structures and towards Black visuality via visual mapping. I began to create visual collages for myself that collated the design work that students were doing since I couldn’t just write words to meet and see my students’ visual designs.

Figure 4: Sample Collages That I Created to Collect and Trace Popular Images that Appear in Multiple Students’ Work in a Given Semester

I also began by drawing out students’ webpages to have a tangible feel for where and how they were virtually placing visual objects. I wrote out hundreds of titles of subpages and formed sentences, letting my body and mind listen to the ways Black Language shaped how students’ webpages were formed and organized (Kynard, 2021). From these embodied and visual encounters with students’ digital work, I now read, see, and frame the Black Cultural-Digital imagination with three movements and moments: Black cultural-spatial contouring, multimedia Blackscapes, and Black navigational messaging.

Figure 5: Black Digital-Cultural Imagination… in PART II

For each of these three modes, I will select and discuss a student whose work I call a guiding vision-example. In each case, I choose a student whose project sits at an earlier point in my teaching, marked as the beginning of the M4BL, because these are the students who later students would say they were emulating and following. Thus, these students can hopefully be as much of a guide for this essay as they were for their peers.

Black Cultural-Spatial Contouring

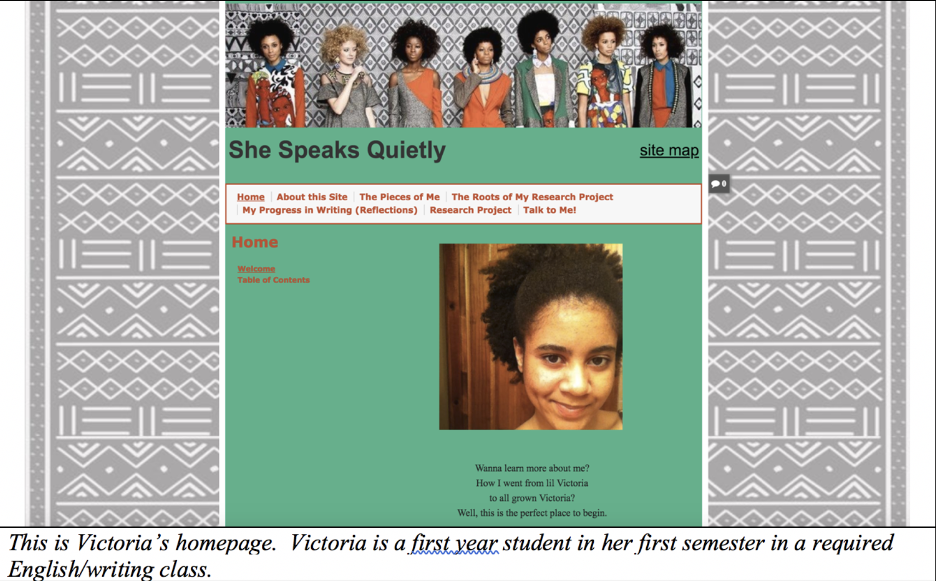

Black Cultural-Spatial Contouring is how I define student deliberation in their color scheme and image selections for headers, main containers, and background areas. Students are manipulating a digital landscape and giving it a new contour based on their own cultural meanings. Victoria will visualize Black cultural-spatial contouring as the guiding vision-example here.

Victoria chooses images of Black women with natural hair for her header to match her own natural hair. The women in Victoria’s header are standing against a gray and white African print that Victoria has chosen to replicate, at least in spirit, in her background. The color orange is repeated in almost all of the outfits with one instance of green. Victoria therefore chooses green and orange as the dominant colors of her website to give her site what she calls a “bold pop.” She argues that, for her, orange and green together exude the spirit of confidence that she had to embrace after going natural the year prior so that now she can kink everything else (Kynard, 2021).

Figure 6: Black Cultural-Spatial Contouring with Victoria

I consider these layered meanings and visuals as a visual mechanism whereby students contour their webspaces. They are manipulating a digital landscape and giving it a new contour based on Black cultural-political meanings. Victoria’s body narrative, in this case in relation to her natural hair, intentionally takes up new space in this new, deliberate contouring of her kinks. The spirit and craft of her body narrative thus extend to how she imagines a digital space should take shape and space also.

Multimedia Blackscape

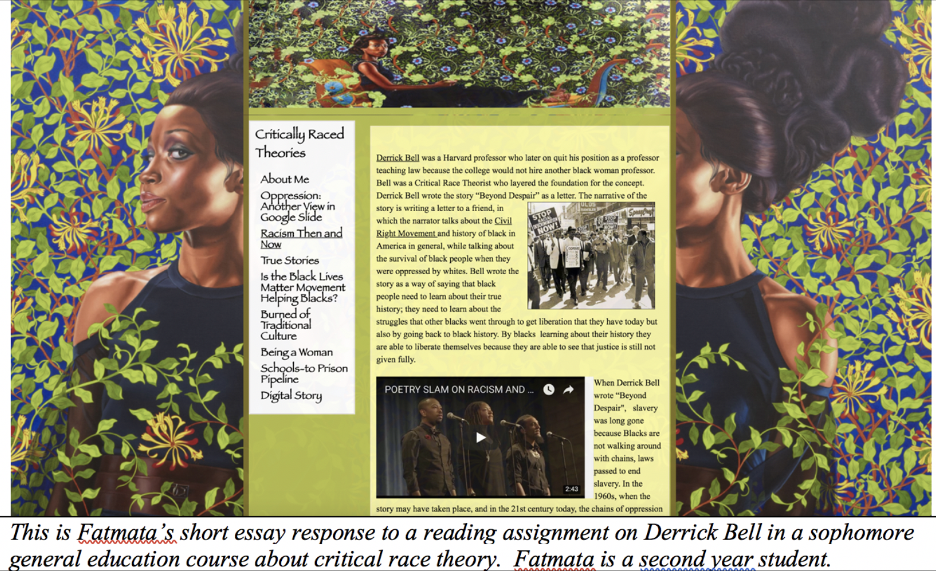

Like Victoria, Fatmata too crafts a Black contour. Her work further builds out this notion of contouring and adds another layer: multimedia Blackscape—the ways that students collect many multimedia artifacts that they wrap their alphabetic text around. Fatmata will visualize multimedia Blackscape as the guiding vision-example here. In her work, you will see a spoken word video and a historical image that she has embedded on her webessay about Derrick Bell on a website that is culturally-spatially contoured with Kehinde Wiley’s art.

Figure 7: Multimedia Blackscape with Fatma

Students like Fatmata collect many multimedia texts to complement their cultural-spatial contouring: short, personal or research narratives curated with race-conscious images, weblinks, and video. My term, multimedia Blackscapes, remixes the words escape/e-scape and landscape and adds Black to it. Students do a specific kind of work in multimedia blackscapes: they remediate their opinions and connections with the course’s assignments alongside the multimedia texts that are impacting them outside of school and merge that work with a Black visual ethos that reflects the Black Diaspora.

Black Navigational Messaging

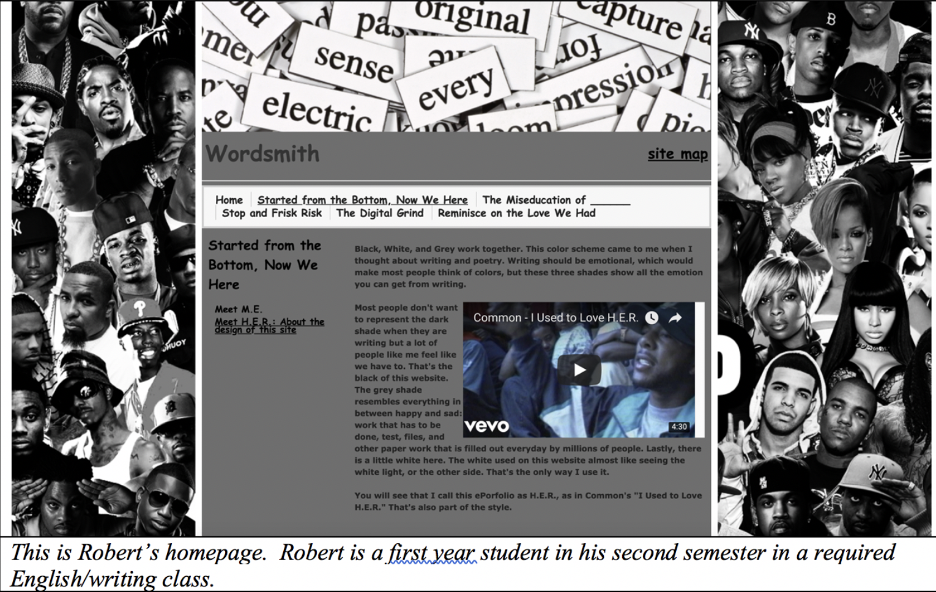

Black Navigational Messaging is how I reference the naming of the main sections and subsections—namely the top-navigation tabs and left-navigation (drop-down) tabs—to further achieve a Black rhetorical place and aesthetic space (that works in addition to multimedia Blackscape and Black cultural-spatial contouring). The section headings, now clickable since they are sections of the website, stand as gateways to Black space. Robert will visualize black navigational messaging as the guiding vision-example here.

Robert shapes representation of Hip Hop literacies with cultural-spatial contouring and multimedia Blackscapes and builds on both with Black navigational messaging. The top navigation is set off in a white space, the only place where Robert argues that you can find anything white on his site. According to Robert, this instance is about the divine white light, not race or whiteness, so his white top navigation is literally imbued with a spiritual, life-and-death quality. All of the words in these titles at the top of the website are the clickable action links organizing the entire space.

Figure 8: Black Navigational Messaging with Robert

“Started from the Bottom, Now We Here” is the section where Robert offers two webpages: a bio and statement of his design choices. He uses rapper Drake’s lyrics to organize this section to emphasize his journey to make it to college and his journey in understanding how to code and customize CSS for a website. On the webpage called, Meet H.E.R.: About the Design of this Site, Robert explains his design decisions. Here, he personifies his website as a woman, to be more specific as H.E.R. He is referencing a Hip Hop classic by Common called, “I Used to Love H.E.R.” (“Hip Hop in its Essence is Real”). Robert’s H.E.R. connects his writing to the history and impact of Hip Hop and also signals his mobilization of his ideas on a digital platform as its own kind of song in homage to Hip Hop history. Robert’s personification of his website is not just the figure of any woman; it is a deeply historied Black Hip Hop woman.

With Robert, we see that Black youth culture and Black language are an obvious flow in these social/digital spaces (Alim). Iconic figures of African descent, a Black lexicon, and the morphosyntactic structures of Black language name the spaces of these websites and mobilize Black visuality (Brock, Baker-Bell). Thus, Black visuality and Black language merge here in a way that cannot be treated separately. The alphabetic/written preoccupation of white, western communication means that we often only see and hear the words and sentences of (digital) communication and not its dynamic re-imaging. We seldom recognize Black visuality as Black vernacular creativity or rhetoric, even when we talk about spaces like Black Twitter, because we only centralize speech and alphabetic texts. As scholars and activists related to Black ASL (American Sign Language) like Joseph Hill (2015, 2017) and Carolyn McCaskill have quite literally and continually shown us, Black language and communication are embodied way further than the ableist confines of spoken and written words (Hill, Lucas et al., Ceil et al., McCaskill et al.). It is a disservice to Black students especially to not see and hear their words in the context of a deliberate and deep Black visual messaging.

During demonstrations of working with the code of this particular platform, I nudge students to be like 1990s Hip Hoppers and so I quote Lil Kim in good measure: “To all my people in the hood, stay fly!” That’s their only requirement. The fact that they go so far beyond my requirements indicates to me how much their digital work represents a conscious, self-driven rhetorical act that is intimately part of current Black liberation struggles: firstly, because the students themselves claim it; but, secondly, also because the broader Movement for Black Lives is also about a visual clapback against an anti-Blackness that targets Blackness as the site of the grotesque. These students’ deliberations toward a new visibility offer us a lens into what resistance quite literally looks when it gestures towards Black peoplehood (Jones 2011, 2017) and should be central to how we imagine digital rhetoric today. Together, these three themes—Black cultural-spatial contouring, multimedia Blackscapes, and Black navigational messaging—represent a kind of 21st century racial audience processing where Black vernacular creativity moves far beyond print or orality and instead structures wider visual and modular expressions of freedom and resistance.

#000000 Countervisual Narrative in a Post-Truth White Supremacist World

Victoria, Fatmata, and Robert explicitly name Black resistance in their webspaces as central to their being in the world today. Young Black people like them in my classes have used the digital to remediate their classwork and situate themselves digitally, publicly, and rhetorically in alignment especially with the Movement for Black Lives, oftentimes at great risk to themselves (Maraj). Therefore, before we begin work on final digital projects, I talk extensively with students about surveillance culture since they are the demographic who will be trolled and appropriated most (Williams). Such conversations and the related readings we engage, however, are really not about a warning or impending doom, but about understanding legacies of oppression and control in relation to the resistance of people of color.

We would do well to remember that COINTELPRO was a multi-faceted, complex FBI operation, a new technology all in its own right, that had as its singular purpose the dismantling of Civil Rights organizations, especially the Black Panther Party (Carson). Black distrust of snitches today—and the "snitches get stitches" discourse—were arguably formed as a response to the infiltration of these organizations which mobilized countless Black Americans to wage war on its own organizational leaders. Between the FBI file of Malcolm X, Huey Newton’s thesis War Against The Panthers: A Study of Repression in America, the Autobiography of Assata Shakur, and the fact that activists like Leonard Peltier and Mumia Abu-Jamal are still in prison, we are not a loss to understand surveillance regimes and Black responses to it. It is also critical here to challenge the tropes of the easily misled and misinformed white supremacists who consume falsified information out of ignorance and therefore criticize or attack Black activists/Black students online. I assure young people of color, whenever I can, that this is an ahistorical rhetoric of white innocence that obscures the fact that white supremacists mean to do us harm. And it is exactly at the moment of Black success that such targeting occurs; we can go all the way back to Ida B. Wells’s Red Record for empirical data on this and, in fact, if we were living in the first Post-Reconstruction instead of the third, some of us could very well end up as what Billie Holiday called “strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.”

I am essentially, asking students to fully acknowledge the violence targeting our bodies— civil deaths and social deaths—not as defeat but in the spirit of Franz Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth. We can have a critical understanding of what Black feminists like Hortense Spillers, Saidiya Hartman, and Tiffany King have theorized as Black fungibility and still also imagine Black life outside of the bounds of a white positionality that imposes itself everywhere. In the meantime, many have done a real disservice to Black students in the politics of digital pedagogies by not foreshadowing or centering the political turmoil of the second #BlackSpring in 2020, the social movements led by Black youth in the U.S. so named as a comparison to the massive protests in the Arab World in spring of 2010, with the first #BlackSpring located in the #BlackLivesMatter uprisings in Ferguson, New York, and Baltimore in 2015 (Beydoun and Ocen). #BlackSpring2020, however, also witnessed a global pandemic under the Coronavirus Crisis whose affects were experienced most acutely in Brown and Black communities. Black youth watched white supremacists rally outside of public institutions across the country, oftentimes fully armed, with no impunity despite state regulations related to required social distancing, masked faces, and shelter-in-place procedures. These same youth watched that same state brutalize them in their unarmed protests against racial violence. We simply cannot set the chorus of our scholarship on an analysis that white supremacists, privileged and digitally mobilized by the state, merely lack proximity to—and therefore understanding of people of color—as if proximity could ever translate to solidarity or transformation.

Instead of ascribing newness to the racism of what many began to call the Post-Truth Era, I signal racialized and colonial histories that frame the context of our contemporary internet cultures with:

- contemporary articulations of longer histories of colonialism, colonization, and racial power/violence (the mobilization of Anti-blackness and white anxiety is now digitized, but is not new)

- The signal of a third Post-Reconstruction that works as backlash against the Movement for Black Lives, marked most clearly by the election of Donald Trump (as a reminder: Reagonomics was the Second Post-Reconstruction in response to the gains of the Civil Rights Movement; Jim Crow was the First Post-reconstruction in response to the gains of Black Emancipation/Reconstruction)

- Ongoing anti-colonial struggles for liberation rooted in feminist/of color/intersectional, anticolonial, queer, trans, and anti-racist praxis

Here are the things that are not new (and not even presented in new, interesting ways): the persistent marginalization of racial and ethnic minorities in current media systems in an “unequally-mediatized world”; ongoing and insufficient attention to race, Blackness, and racial inequality in curricula; and hostile institutional climates on our campuses, in our professions, and across institutional spaces for BIPOC.

Tina Campt’s work especially conveys the visual textures of oppression and Black resurgence within such racialized regimes. She reminds us that a radical visual archive of the African diaspora sits right alongside deliberate state, global, and daily violence that intends solely to count, catalog, categorize, surveil, and degrade Black subjects. She further warns that we need to change our very modalities to understand the alternative affect that everyday Black visuality offers to creative fugitivity. She situates contemporary artistic practices in Black histories of refusal that offer us a Black persistence on futurity. Self-expression as futurity thus moves us past the simplistic binary of agency and subjection, especially in alphabetic texts, even when those attempts at self-expression are not fully realized or successful (Nelson).

I turn here now to a young Black woman in one of my classes, Diamond, to allow us an intimate view of the metaphysical/metapolitical condition of Black visuality that Campt points us towards. Diamond created a website called “We'll Fight For Us--- Young. #000000. Feminist.” Instead of writing out the words, black, she used the html color code: #000000. She is intentionally referencing the binary code, the system of binary digits 0 and 1 that represent a letter, digit, or other character in computers and other electronic devices. She is also simultaneously referencing social media with the hashtag sign. She marks Black feminist digital ethos with her invention of the terminology of “Young. #000000. Feminist.” in order to remind us that the binary of white/black and woman/man, all of which are white colonial projects, now attempts to oppress her and is reinvented in the logic of digital spaces. In doing so, she captures what Charles Linscott argues is a “recursive dynamic” between resistance and oppression in Black life: digital technologies continually offer the “promise of global reach and rapid dissemination” that is always simultaneously embedded “within structural anti-blackness” (107). As we see with Diamond, she neither discards the opportunities afforded by digital spaces nor wholly celebrates them and instead circulates her own critical Black digital-cultural motifs towards an alternative futurity of the #000000 digital. In that regard, Diamond teaches us what countervisual narratives in a Post-Truth, white supremacist world understand and do.

Victoria, Fatmata, Robert, and Diamond as Pedagogical Timeline of the M4BL

Victoria, Fatmata, Robert, and Diamond are the four students who catalyzed the central definitions and framings of this essay: 1) Black cultural-spatial contouring, 2) multimedia Blackscape, 3) Black navigational messaging, and 4) countervisual narrativization in a Post-Truth white supremacist world. I have attempted to honor bell hooks’s demand for a “documentation of a cultural genealogy of resistance” (151) that highlights the everyday Black cultural practices that transform “ways of looking and being” (151) and to do so in a way that harvests its own oppositional practice. For Victoria, Fatmata, Robert, and Diamond, the cultural genealogy of their Black digital-cultural imagination is intimately connected to the M4BL, the timespan in which I met all of them.

There was once a time in my academic life where my memories were marked by a series of important landmarks: first day as a high school teacher, first day as a college teacher, graduation from my PhD program, hostile administrators, multiple moves to different jobs, new colleagues/ comrades/ students. All of that still holds true but as of April 2012, I remember time and place as a teacher-scholar through the timeline of the M4BL. Today, when I think of Florida, I see it vividly in my mind’s eye as the home of the Dream Defenders, the students from Gainesville, Tallahassee, Miami, and Orlando who waged a 40-mile protest after Trayvon Martin was murdered; George Zimmerman wasn’t even charged with murder until after their protest. My mental vision-board automatically sees Trayvon, hoodies, the face of Trayvon’s mother, Sybrina Fulton, and the now iconic image of Trayvon’s father locking him in an embrace kissing him on the cheek.

2013 became a watershed year for the memory banks of my teaching and classroom experiences. In July of that year, George Zimmerman was acquitted and #BlackLivesMatter was invented. I remember the heat on my back, the melting oil in my afro, and the flashing lights on the day that I participated in the sit-ins at Times Square for Trayvon. I still remember what I wore and what bathrooms I snuck into those days, the first of a series of nationwide protests. That fall I started at a new college, vaguely feeling like my classrooms would look and feel differently, but unable to fully chart how until I met the students and their Black visual imaginations who I have traced here. I met Tanisha and Robert as first-year students where the first-year writing classroom was the space in which they wrote the M4BL across their texts.

I learned about Renisha McBride’s murder in a classroom when a student, Brittany, told me what happened, reading the events to me from her cell phone, all while wearing a T-shirt boldly emblazoned with #BlackLivesMatter. These images would repeatedly adorn her web projects. It should come as no surprise that Victoria learned of my class and teaching style from Brittany in the previous semester. Victoria’s Black cultural-spatial contouring was nothing that I taught; she came to class fully intentioned and fully formed from a peer group and cultural styling that explicitly connected her and her peers to the M4BL.

2014 rings clear as a bell. It was another summer of mourning. In July, Eric Garner was murdered by police in Staten Island, NY. As someone who lived in New York City, #BlackLivesMatter hit home again and #ICantBreathe joined the lexicon. By August, Michael Brown was murdered by police, and I even started watching football differently when, in November, five players from the St. Louis Rams came out on the field that fall gesturing #HandsUpDontShoot in solidarity with protesters across the country, and that was before Kaepernick took the knee. Less than two weeks before the Rams game, 12-year-old Tamir Rice was killed on a playground in Cleveland, Ohio by police for holding a toy gun; and Akai Gurley was killed by police in a stairwell of a housing project in New York City. By December, LeBron James and Kyrie Irving wore "I Can't Breathe" t-shirts while warming up for Monday night's game at the Brooklyn Nets, my own hometown at the time. Brooklyn won that night and it had nothing to do with the final score. I see this chronology not as a list of dates but through the collection of visual images curated in my students’ digital projects, visual outlines that I did not assign but that they pursued themselves. Fatmata, who called herself a Brooklyn Black girl by way of Africa, celebrated that win with me. She also pushed me to notice more deeply all of the multimedia embedding that students did across their webspaces as they were literally archiving their intellectual-media work in the M4BL for themselves.

Fatmata also helped me connect the Black visuality of students’ work to the world of Black art with her love of all things Kehinde Wiley and Mickalene Thomas, two contemporary Black artists who represent critical interruptions in centuries of European and American portraiture. I began to see these artists’ work as a canvas onto which the collage of Black/ queer/ feminist activism is also constructed. In fact, I connect artists like Wiley and Thomas with this moment’s re-birth of the visual album, especially Black women’s central role in that visual movement.

I remember ringing in the new year in 2015, not in January, but a few weeks later when Kimberly Crenshaw released documents online of Black women killed by police with the hashtag #SayHerName. The soundtrack to these memories are as sonic as they are visual. Even in February of 2016 when Beyonce dropped “Formation,” I remember that moment as a Black Feminist project in the M4BL (along with the larger visual project of the album, Lemonade) where she featured “stop killing us” as graffiti in the video for the song. Interspersed between shots of the graffiti, we saw a young Black child dancing in front of a line of police in riot gear who later raise their hands up too, like so many Black youth were still doing. It seems like I have seen every gif that stands in witness to Lemonade on my students’ digital projects.

There are many more personally embodied moments. In the aftermath of Baltimore’s protests in the 2015 murder Freddie Gray, I learned of organizations like NetRoots, the national convention of cyber activists, only when #BlackLivesMatter activists interrupted and challenged the whiteness of the national conference. When I walked the campus of Mizzou in 2019 along with graduate student activists in the English department there who participated in the 2015 protests, it was like I had been to that university before. Of course, I hadn’t, but the iconic images of those college students meant that the campus landmarks held personal meaning for me as I saw firsthand the locations of Black student protest. I have so many hashtags in my head, once known merely as the number sign or pound, that I am surprised that I can even form sentences today without this symbol.

#BlackLivesMatter became more than a moment, a social media trend, or a hashtag and stands as a movement, one whose origins and contemporary ideological origins are rooted in Black Queer feminisms (Carruthers, Ransby). In my own personal narrative timeline that I am sharing here, the M4BL has shaped new geographic mappings, embodied memories, relationships to time, and a pedagogical timeline.

By 2016, I had also experienced a wider, whiter array of digital scholarship in a way that was completely incompatible with what students like Victoria, Fatmata, Robert, and Diamond were creating in the context of their M4BL. Today, I remember the year of 2016 through the names of #PhilandoCastile and #AltonSterling and the conference that I attended on a college campus that fall. It followed the summer where on July 5, Alton Sterling was killed by police in Baton Rouge, Louisiana and on July 6, Philando Castile was killed by police in Minnesota. The conference was sponsored by a flagship, predominantly white college campus in Louisiana where the words #BlackLivesMatter were chalked all over the campus sidewalks. The main building which held classrooms and our keynote presentations had flyers postered on every wall alongside advertisements with two hashtags: #PhilandoCastile and #AltonSterling. In fact, there were print-outs taped high to the beams on top of the conference’s book display. I can never un-see this campus this way and yet many of the conference’s presenters of all things digital had all but erased this Black presence. After attending yet another session focused on digital rhetorics and digital literacies, I finally raised my hand and asked for some specific connections to Brown and Black youth. I like to do this at conferences since I am constantly asked how my research and scholarship on Black and Brown college students relates to white students. I trip up white folk and flip that question back on them: so, what does this have to do with Brown and Black folx? I seldom hear anything but pure foolishness where white scholars self-righteously excuse and exempt themselves from all racial analyses because they only see one or two Black students in their classrooms. The foolishness of the responses to my question in 2016 is etched in my mind.

The particular session where I asked my stymieing question featured a large panel of mostly white graduate students and a white faculty mentor who all taught at the college hosting the conference. Their work was an exploration of digital literacies and digital rhetorics, in their own lives and in their classrooms, and they were in the final stages of proofing their collaborative publication that explored this topic. When I asked how their work related to Black and Brown college students like those I teach, where as an example, their work is oftentimes qualitatively and quantitatively different from white students, things just got ridiculous. The moderator issued an elaborate lengthy suggestion that I use a company like Coca-Cola to model for my students how involved a digital footprint really is. I was stunned. I mean, this is a rhetoric scholar suggesting OUT LOUD (note: this means that I could hear her) that a Black feminist might want to look to Coca Cola for example and inspiration. There was an animated exchange with significant audience participation to try and come up with the name of a Brown or Latinx scholar who does digital rhetoric. No one could give the full name or title of a single book or author. As a reminder, to get to this break-out session, we had to walk on top of a campus sidewalk that was chalked with #BlackLivesMatter. Whenever we entered the auditorium that held the keynote, we passed flyers with the hashtagged names of Philando Castile and Alton Sterling plastered to the walls. I even met some of the Black students on this campus from just walking across campus and got a feel for their vexed relationship to the campus climate. And here we were with dozens of scholars teaching writing on this campus who could not account for the Black Digital Lives right there in front of them, underneath their feet, and plastered to their walls.

This moment, now part of my own internal M4BL timeline, is one which we have now all inherited. That presentation has since been published and is part of the professional knapsack of white scholars that has resulted in their material rewards mobilized in the form of fellowships, job searches, tenure and promotion. That presentation is now also part of an extant literature that other scholars read and cite. Four years later, the city that housed that academic conference—Louisville—witnessed wide-scale protests triggered by the brutal police murder of an emergency medical technician, Breonna Taylor. No one at the college or at the conference should have been unprepared to respond to or understand the possibility of this kind of contemporary white violence had they just listened to and saw the Black students right there in front of them. Like I already said, these Black students had laid out their experiences and feelings literally right underneath our feet and plastered it all to the walls. This is the context in which I met Diamond who literally coded her understanding of white supremacy and the gender binary into her CSS to achieve a Black countervisual narrativization of the Post-Truth era.

I want to be clear here that I am not talking about an inclusion model where we add in new voices to established frameworks, a process that assumes white canonical texts, experiences, and voices only need folk of color “bussed in” for new racial integration. Instead, I look to my students’ Black digital-cultural imagination as what Pritha Prasad calls “an alternatively embodied, relational rhetorical imaginary” (7). By the summer of 2020, Black youth in my state had witnessed the audio/visualized and/or socially mediated Black deaths of George Floyd, Tony McDade, Nina Pop, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery after starting the school year with the murder of Atatiana Jefferson right in our campus’s neighboring community. Black youth have been organizing, creating, and following Black digital content for the purposes of re-imagining/re-imaging Black life and yet campus digital platforms and vast majority of digital rhetoric are stunningly anti-Black in how they are visually organized, anti-Black in how language/identity politics are represented, and anti-Black in the ways the digital is purposed.

At this juncture, many majority-white academic communities imagine themselves to be making a social turn towards racial justice. However, the public/professional statements that we saw in 2020—written a full seven years after the first utterance of #BlackLivesMatter and when the M4BL dovetailed with the pandemic and white corporate sympathies—are not even the beginning stages of the racial harm that must be repaired. Folk who had no sustained critique or refusal of violence against Black bodies cannot be trusted to have a radical critique now. For my part, I will not be looking to those places that perform solidarity in the times of national, white-approved attention but did not step up to the plate beforehand. I will spend my time and history/moment-making with the young people who visualize alternative Black futures in the daily work they do to actually revise the real (digital and otherwise) codes of our universities and social systems. Their Black digital-cultural imaginations compose a future worth seeing.

Alim, H. Samy. Roc the Mic Right: The Language of Hip Hop Culture. Routledge, 2006.

Baker-Bell, April. Linguistic Justice: Black Language, Literacy, Identity, and Pedagogy. Routledge, 2020.

Brock, Andre. Distributed Blackness: African American Cybercultures. New York University Press, 2020.

Campt, Tina. Listening to Images. Duke University Press, 2017.

Carruthers, Charlene. Unapologetic: A Black, Queer, and Feminist Mandate for Radical Movements. Beacon Press, 2018.

Cohen, Cathy and Sarah J. Jackson. “Ask a Feminist: A Conversation with Cathy J. Cohen on Black Lives Matter, Feminism, and Contemporary Activism.” Signs, vol. 41, no. 4, 2016, pp. 775–792.

Elam, Harry J., Jr., and Kennell Jackson. Black Cultural Traffic: Crossroads in Global Performance and Popular Culture. University of Michigan Press, 2005.

Fleetwood. Nicole. Troubling Vision: Performance, Visuality, and Blackness. University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Ford, Tanisha. Dressed in Dreams: A Black Girl's Love Letter to the Power of Fashion. St. Martin’s Press, 2019.

Hartman, Saidiya. Scenes of Subjugation: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in 19th Century America. Oxford University Press, 1997.

Hartman, Saidiya and Frank B. Wilderson. “The Position of the Unthought.” Qui Parle, vol. 13, no. 2, 2003, pp. 183-201.

Haymes, Stephen. “Black Culture Identity, White Consumer Culture, and the Politics of Difference.” African American Review, vol. 31, no 1, pp. 1997, 125-128.

Hill, Joseph. “Language Attitudes in Deaf Communities.” Sociolinguistics and Deaf Communities, edited by Adam Schembri and Ceil Lucas, Cambridge UP, 2015, pp. 146–174.

Hill, Joseph. “The Importance of the Sociohistorical Context in Sociolinguistics.” Sign Language Studies, vol. 18, no. 1, 2017, pp. 41-57.

hooks, bell. Art on my Mind: Visual Politics. The New Press, 1995.

Hunt, Sarah and Cindy Holmes. “Everyday Decolonization: Living a Decolonizing Queer Politics.” Journal of Lesbian Studies, vol. 19, no. 2, 2015, pp. 154-172.

Jones, Kellie. EyeMinded: Living and Writing Contemporary Art. Duke University Press, 2011.

Jones, Kellie. South of Pico: African American Artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s. Duke University Press, 2017.

King, Tiffany. “The Labor of (Re)reading Plantation Landscapes Fungible(ly).” Antipode, vol. 48, no. 4, 2016, pp. 1022-1039.

Kynard, Carmen. “‘Pretty for a Black Girl’: AfroDigital Black Feminisms and the Critical Context of ‘Mobile Black Sociality.’ ” Mobility Work in Composition, edited by Bruce Horner, Megan Faver Hartline, Ashanka Kumari, and Laura Sceniak Matravers, Utah University Press, 2021, pp. 82-94.

Kynard, Carmen. “This Bridge: The BlackFeministCompositionist’s Guide to the Colonial and Imperial Violence of Schooling Today.” Feminist Teacher, vol. 26, no. 2-3, 2018, pp. 126-141.

Lockett, Alexandria. “What is Black Twitter? A Rhetorical Criticism of Race, Dis/Information and Social Media.” Race, Rhetoric, and Research Methods, edited by Alexandria Lockett, Iris D. Ruiz, James Chase Sanchez, & Christopher Carter, University Press of Colorado, 2021, pp. 165-213.

Lucas, Ceil, et al. “The Intersection of African American English and Black American Sign Language.” International Journal of Bilingualism, vol. 19, 2015, pp. 156–168.

Maraj, Lou. Black or Right: Anti/Racist Campus Rhetorics. Utah State University Press, 2020.

McCaskill, Carolyn, et al. The Hidden Treasure of Black ASL: Its History and Structure. Gallaudet University Press, 2011.

McKittrick, Katherine. "Plantation Futures." Small Axe, vol. 17, no. 3, 2013, pp. 1-15.

McKittrick, Katherine. Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle. University of Minnesota Press, 2006.

Neal, Mark Anthony. Soul Babies: Black Popular Culture and the Post-Soul Aesthetic. Routledge, 2002.

Nelson, Charmaine. Towards an African-Canadian Art History: Art, Memory, and Resistance. Captus Press, 2018.

Powell, Richard. Cutting a Figure: Fashioning Black Portraiture. University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Prasad, Pritha. “Beyond Rights as Recognition: Black Twitter and Posthuman Coalitional Possibilities.” Prose Studies, vol. 38, no. 1, 2016, pp. 1-24.

Ransby, Barbara. Making All Black Lives Matter: Reimagining Freedom in the Twenty-First Century. University of California Press, 2018.

Sharpe, Christina. In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Duke University Press, 2016.

Spillers, Hortense. “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book.” Diacritics, vol. 17, no. 2, 1987, pp.65-81.

Thompson, Krista. Shine: The Visual Economy of Light in African Diasporic Aesthetic Practice. Duke University Press, 2015.

Tuck, Eve. “Suspending Damage: A Letter to Communities.” Harvard Educational Review, vol. 79, no. 3, 2009, pp. 409-427.

Wallace, Michele. Dark Designs and Visual Culture. Duke University Press, 2004.

Wallis, Brian and Deborah Willis. African American Vernacular Photography: selections from the Daniel Cowin Collection. International Center of Photography, 2005.

Williams, Sherri. “Digital Defense: Black Feminists Resist Violence with Hashtag Activism.” Feminist Media Studies, vol. 15, no. 2, 2015, pp. 341-44.

Willis, Deborah. The Black Civil War Soldier: A Visual History of Conflict and Citizenship. New York University Press, 2021.

Willis, Deborah and Barbara Krauthamer. Envisioning Emancipation: Black Americans and the End of Slavery. Temple University Press, 2012.

Wynter, Sylvia. “Beyond Miranda’s meaning: Un/Silencing the ‘Demonic’ Ground of Caliban’s Woman.” Out of the Kumbla: Caribbean Women and Literature, edited by Carole Boyce Davies and Elaine Fido, Africa World Press, 1990, 355-372.

Wynter, Sylvia. “Towards the Sociogenic Principle: Fanon, Identity, the Puzzle of Conscious Experience, and What It Is Like to Be ‘Black.’” National Identities and Sociopolitical Changes in Latin America, edited by Mercedes F. Durán-Cogan and Antonio Gómez-Moriana, Routledge, 2001, pp. 30-67.