MYINTROTOLETYAKNOW

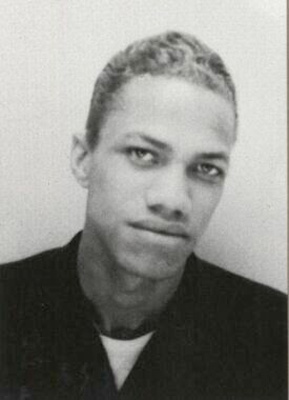

Everyone in 1968, it seems, was teaching composition with the Beatles. But I think I’ve only run into maybe three people in the last years who, like me, teach with rap. Which is odd when you think about the aims of a course in verbal meaning, one of which should definitely be to enable students to express and record truth. And despite all the many things you could say about this complex, contradictory popular genre, rap is loaded with truth, a truth about language, desire, style, and humanity. It’s a truth that might well be rooted in one culture, but it’s also a larger American truth, an ethos that evolved in response to this culture we all ultimately form. And it’s an ethos, of course, that goes directly against what’s been instituted as official culture (so call this anti-white-supremacy theory). I find the message of that truth conducive to writing instruction—both in terms of the way it allows language and form to be more charged (and accessible) than under the normal conditions of classroom writing, as well as in how it gives students the opportunity to make verbal meaning in a context that’s universally significant and personally affecting. If Malcolm X is cocaine, a jolt along your nerves able to heighten perception and energize, then rap is the crack form of Malcolm—quicker, cheaper, more intense (also more addictive). A study of rap, particularly gangster rap, almost immediately throws you into the mix and demands fresh insight on issues of race, class, gender, and sexuality. Recycled racial stereotypes (even as rap indulges in them) ultimately won’t do, except in the mainstream media: see, for example, Newsweek’s November 29, 1993 cover story, featuring what looks like a mug shot of Snoop Doggy Dogg on the cover, overlaid with the question, “When is Rap 2 Violent?” And “mainstream” does not simply equal “white” here: rap is officially put under race-based suspicion by many black leaders, especially C. Delores Tucker, an African American political official, who feels “gangster rap is negatively influencing our youth. This explains why so many of our children are out of control and why we have more black males in jail than we have in college” (United States 12). Students of rap, then, quickly realize its reception in our culture marks a struggle over the representation of race and class, one that compels their contribution. So after a few weeks of writing about rap, anybody but a die-hard racist can be doing a critique of the media’s depiction of rappers or a study of the economics of racism in the music industry. Malcolm’s story is unfortunately distanced for a lot of my students; like powder cocaine, it’s out of reach to most of them. “That was then,” they say, even as I bring in news account after news account to show that, hey, it’s now, too. Rap’s dramas, however, are ridiculously immediate: even though the urban-poverty imagery of 1982’s “The Message” is over 13 years old, it might as well describe video footage shot yesterday. So to get people interested in learning to perfect a voice on issues that count, I have a first-year writing course centered on rap. But gangster rap’s pay-off as material for writing comes at a cost that must be figured carefully. Rap is alternative, almost cultish: “I’m still around for you,” 2Pac tells his listeners, “keeping my sound underground” (Strictly). Exactly what happens when the underground surfaces in a university writing class? If rap kicks the truth, just what is the truth that it kicks? For me—and this explains why I, along with most of my students, am willing to negotiate an aggressive landscape of sexism, misogyny, homophobia, violence, and even racial demonization—rap’s on-going project centers around the notion of heart. That notion is worked out in rap in both form and language. Rap, again like Malcolm, is all about using a kind of plainspeak grammar and lexicon (even if slang-based), charged with as much poetry as one can muster, to fashion blunt narratives of the human heart, narratives which become a desperate politics of a basic decency. For my students and I, rap offers substance, provoking desire to make meaning on issues that count in our culture, no matter what a student’s race, gender, class or previous schooling. Moreover, rap is all about literacy—getting the skills to come correct—but even as it supports our goals, it skews the scene of contemporary writing instruction so that the focus shifts from strictly textual meaning to encompass language as performance. Style counts, not as belletristic prose or academic discursivity, but as character for humanity. Textuality becomes essential for life in a way it just isn’t in most school-sponsored work, in the way it offers students (and teachers) a heuristic for reading the world. I offer in this text, then, some snapshots from several years of teaching writing classes centered around rap music—both snippets from students’ writing and commentary in the courses, as well as my own reflections—in order to trace both the opportunity offered by rap for composition, as well as the way students rise (or don’t) to the occasion.

|