|

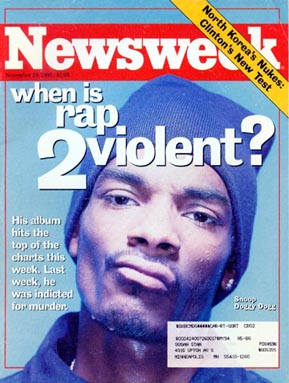

I’m almost sympathetic to those white students entering my course on writing about the texts of rap who immediately size up the project with a restless frustration, black folk all up in their faces again. It’s the same restless frustration (suffused with racism) that led, several years back on my campus, to the young man who wanted to start a White Student Union. I’d be more sympathetic, though, if that attitude had some basis in reality. Exactly just how often are university students actually dealing with matters of blackness in the curriculum, especially in the politically incorrect way rap presents such matters. In my first-semester writing classes, for example, we look at Hirsch’s Cultural Literacy list, and I always wonder, Where’s Yacub? Where’s Elijah Muhammad? Louis Farrakhan isn’t on the list but Jerry Falwell is . . . what’s up with that? These obvious cultural, curricular aporia play themselves out in student discursivity. I’m thinking of those white students who seem inordinately fond of using the n-word: Take Angie, who was generally sympathetic to what she learned about rap (one of her papers developed the idea that “Rap music has never been my favorite, but listening to the feelings and emotions that Tupac raps about makes me realize how difficult life in Black America really Is”), but who sprinkled her paper with observations like the following: what I got out of the song was that he was trying to make a statement, by telling everyone what his feelings are about niggers in the hood.And that’s from someone without any otherwise apparent wickedness. Another, more cynical, student wrote, “One quick question. Why is it considered so horrible if someone uses the word nigger, but every rapper talks about his friends or foes as a nigger? NWA even used the word in their name.” Some white students just cannot control their intrigue with the term; it liberates them somehow to have a legitimate occasion for voicing it. They speak the language they came into class with, that code of casual cruelty, of brutal kindness, of genial despotism, a code which has survived, grown, spread, and congealed into a national tradition that dominates, in small or large measure, all black and white relations throughout the nation until this day. (Wright 18)That code is a language-as-logic, in the same way Wright claims “Black” is not a race but a fate, a law, both written and unwritten, “the most unanimous fiat in all American history” (30). That law keeps working its destiny, particularly over the Stagolee figure, otherwise known in folklore tradition as the “bad nigger”: the criminal punishment of African Americans in the late nineteenth century had as a primary function the “breaking” of recalcitrant “bad niggers” . . . [with] the two most common forms of punishment . . . the chain gang and convict lease system. Both forms of punishment were characterized by forced labor, inhuman living and working conditions, and an extremely high mortality rate. (Roberts 178)Students in my class pursue a personal research question about rap throughout the semester. They usually take on topics like race, gender, economics, oldschool, censorship, the media, or regional issues. And then there was Troy’s paper—weird, short, tormented (precisely, it turned out, like its author). Troy’s focus was rap itself, especially rap as the topic of a class: “Where do we draw the line? How far will it have to go until something is done? These are the questions I contemplate every Monday and Wednesday [i.e., days our class met].” Troy’s purpose? To contest the class, the material, but mostly the people who produce it: In conclusion, the excuse: “it’s a reflection of a culture” can only take the rappers so far. Did gangsta rap create the culture in which they represent or are they just stating it the way it is: killing someone and getting laid is cool and your only a man unless you can screw as many girls as days in the week.As in the larger culture, when someone attacks rap, it's almost always a coded attack on young black men. Troy is like one of those whites, in the days directly following emancipation, who “continued to view almost any black person who challenged their authority or right to define black behavior and social roles as a ‘bad nigger’” (Roberts 177). Or, the “big nigger,” as Troy puts it, when he reflects in an e-mail message on the parallels someone in class drew between Snoop Dogg and Kurt Cobain as pop victims of nihilism. Troy will have none of it: “[Cobain's] accomplishments deserve more than referring to him through his suicide. . . . But Snoop’s problem he has is different than Cobain’s. Snoop is trapped in the reality of being a ‘big nigger’ (as his lyrics would say) he put himself in this position.” It is interesting to wonder just how Snoop put himself in the position of being a “big nigger” (and his lyrics never say this, of course; the parenthetical comment is just Troy feeling the need to legitimize his use of the slur), other than by making it clear to people like Troy he doesn’t give a fuck about them. But I do agree with Troy on one point, though; black men are definitely getting screwed seven days a week: Black males are more likely than any other group to be spontaneously aborted. Of all babies, black males have the lowest birth weights. Black males have the highest infant mortality rates. Black males have the greatest chance of dying before they reach 20. Although they are only six percent of the United States population, blacks make up half the male prisoners in local, state and federal jails. Thirty-two percent of black men have incomes below the poverty level. Fifty percent of black men under 21 are unemployed. (Dyson, in United States 31-32)Dyson, in discussing how the victimization of black males has been compounded historically through demonization, provides a context for Troy’s critique: “From the plantation to the postindustrial city, black males have been seen as brutishly behaved, morally flawed, uniquely ugly and fatally oversexed” (United States 32). There is a line of inquiry, then, for a skeptic like Troy. He could investigate how gangster rap implicates itself in that demonization. That’s the tack Delores Tucker takes: “They are just the new Step n’ Fetchits. . . . Amos and Andy of the 1990’s” (Dawsey 60). (Or, currently, Rev. Al Sharpton: “This hip-hop culture must use their music, their influence to correct what's wrong, not to continue to perpetuate what's wrong, not continue to promote what's wrong. They have the power to do that. And if they really want to have an impact on society, they must change their focus and show America the best of us instead of the worst.”) But, lacking any sympathy, Troy can’t conceive of such a strategy; he can’t see beyond the unanimous fiat of race. And so his major research paper purports to compare gangster rap to female punk groups, to show how racist and sexist gangster is and how anti-racist and anti-sexist punk women are, but it’s really an excuse to deny any complicity and vent against “bad niggers” (who now include bell hooks): Gangster rap deals with the blaming of all white americans. . . . Gansgster rap’s tendency to generalize the entire white population is invalid. Staements such as “The White man” and “The white community” used numerous times by Black activists are inconclusive. . . . Bell Hooks even goes as far as referring to the white society when discussing the problem of Black women being alienated (33). The white society. I find myself being placed in this category but I don’t believe in what Hooks is telling me I believe . . . gangster rap has yet to show there is some point behind all the negativity and violence.If only Troy had been a student when Eminem dropped The Eminem Show; I would have loved to hear his take on lyrics like, “Let’s do the math: if I was black I woulda sold half. I ain’t have to graduate from Lincoln High School to know that”; “See the problem is I speak to suburban kids, who otherwise woulda never knew these words exist, whose moms probably woulda never gave two squirts of piss ‘til I created so much motherfuckin’ turbulence”; or “Hip-Hop was never a problem in Harlem only in Boston, after it bothered the fathers of daughters startin’ to blossom.”

|