Kristopher M. Lotier, Hofstra University

(Published July 17, 2018)

In a recent monograph, Sianne Ngai declares the “interesting,” the “zany,” and the “cute” to be (eponymously) Our Aesthetic Categories. Each term is a relatively new addition to the English language (14-15). But, more importantly, she argues, “These three aesthetic categories, for all their marginality to aesthetic theory and genealogies of postmodernism, are the ones in our current repertoire best suited for grasping how aesthetic experience has been transformed by the hypercommodified, information-saturated, performance-driven conditions of late capitalism” (1).[i] The three “index—and are thus each in a historically concrete way about—the system’s most socially binding processes.” The zany concerns production (especially with reference to affective or emotional labor), and the cute points to consumption (as in “it’s so cute, I could just eat it up”). In contrast, the interesting indexes circulation, inasmuch as it is an “aesthetic about difference in the form of information and the pathways of its movement and exchange” (1).

The interesting is not particularly concerned with what information a text includes per se or with how that information is arranged. It refers instead to what has already happened to that information by the point of consumption: how and how often it has been articulated, processed, dis-membered, refined, re-framed. It also verbalizes an inchoate and perhaps (otherwise) inarticulable sensation, indicating somehow the flow of information into, through, and out of circulatory networks, as well as one’s own placement in the flow. Ngai follows Gregory Bateson in defining information as “a difference which makes a difference” (145). Thus, to the extent that interestingness indicates “difference in the form of information,” its definition might be restated as difference in the form of differences that make a difference—which is to say, paradoxically, within a sea of undifferentiated data.

In recent years, compositionists and rhetoricians have theorized writing as a function of ecological factors (Edbauer; Rickert) and investigated how delivery, distribution, and circulation determine the impact a text can make. It is in this light that I examine the interesting, a category that affectively registers the movement of information. As recently as 2000, John Trimbur could point to a neglect of delivery among the canons of rhetoric, concluding that its dismissal had “led writing teachers to equate the activity of composing with writing itself and to miss altogether the complex delivery systems through which writing circulates” (189-90). He therefore affirmed an ethical and political imperative: to redefine delivery as “inseparable from the circulation of writing and the widening diffusion of socially useful knowledge” (191). While Trimbur identified delivery and circulation as inseparable, they are not the same thing. Parsing their distinction, Laurie Gries argues that circulation is “largely beyond a designer’s control, unlike distribution,” which I take to be a synonym of delivery, and “which is a deliberate process,” involving “intentional strategies” (344). To be sure, many have heeded Trimbur’s call, studying the multi-layered networks through which (and the multi-modal forms in which) information is transmitted and re-transmitted. Indeed, by 2009 James Porter could identify delivery as a metonym for writing within digital spaces, the excluded term now standing in for the whole. Likewise, a few years later, Gries could plausibly demonstrate an emerging sub-field of circulation studies, which, as she notes, “investigate[s] not only how discourse is produced and distributed, but also how once delivered, it circulates, transforms, and affects change through its material encounters” (333). In her work, Gries also draws attention to an object’s “rhetorical becomings” by focusing on futurity: “The strands of time beyond the initial moment of production when consequences unfold as things circulate, enter into diverse kinds of relations, and transform across form, genre, and media” (337). A sensation attaches to this futurity: the interesting. It is one of the “consequences [that] unfold.” Or, stated differently: interestingness is what information circulation feels like.

In studying circulation, scholars have utilized mathematical or technological metaphors, focusing on grids and networks; biological ones (most obviously, virality); and those drawn from the physical sciences, such as rhetorical velocity (Ridolfo and DeVoss). Many have employed new materialist approaches, as well, exploring the constitutive roles that nonhuman actants (and the post-humans they co-constitute) play in the circulation process.[ii] I admire and appreciate this work. Perhaps there’s still room, though, to ask basic questions about the role that humans’ all-too-human affective responses play in information circulation. An algorithm can tell you what people seem to find interesting; it can’t (yet) tell you why they’re drawn to it, nor can it meaningfully describe the subtleties of the experience. Like a hunch, the sense that something is interesting offers no answers, only a starting place. Examining the interesting, then, provides a useful supplement to those more technical, less (conventionally) “humanistic” concepts.

To theorize the interesting, I turn next to Ngai’s Our Aesthetic Categories, several of the texts she references therein, and a recent article by architect Mark Dorrian. Following that overview, I investigate a perhaps-odd example: the Reddit thread “Today I Learned,” in which anonymous users provide information regarding something they have learned that day. While this sub-Reddit ostensibly operates in a show-and-tell fashion, it also provides a testing ground for interestingness, which is always pressing, held in suspension, and up for argument. It is thus an apt site for studying how the interesting d/evolves within reasonably closed information circulation networks.

In the concluding section, I draw two key insights from Sara Ahmed’s scholarship: first, a sign’s affective intensity (whether positively or negatively “charged”) accumulates and/or intensifies through circulation. That is, its capacity to construct or destroy social bonds changes as it (re)circulates. Second, even in determining whether information is or is not circulating (a seemingly objective question), one typically judges by way of affective dispositions. If a piece of information feels interesting, one senses that it is circulating. Uninteresting information, by contrast, often appears to “block” the system(s) through which it circulates.

Interrogating the Interesting

There’s no reason to sugarcoat it: the interesting is “undeniably trivial,” especially when compared to certain other aesthetic judgments—goodness and beauty and sublimity—which carry “theological resonances” (Ngai 18). In calling something beautiful or sublime or good, one seems to draw an even greater distinction between self and external thing, expressing admiration but acknowledging distance. Such things thus often seem foreign, unapproachable, final, conclusive. For instance, if we consider the etymology of the term “sublime”—“sub” + “limen”: up to the threshold—we see its wordless wonder as a function of our sheer inability to grasp it. The sublime taxes our faculties; it is almost-but-not-quite too much to bear. The interesting is also defined comparatively. But, if the sublime arises at and illuminates the upper end of the perceptive spectrum, the interesting works along the lower fringes. It is provisional and temporary, close-at-hand. It offers a reminder that “[t]o aestheticize something is not necessarily to idealize or even revere it” (23). Any judgment of interestingness seems to draw the evaluator toward the thing in question, so as to understand it better.

Beauty and sublimity seem somehow more directly immanent to the thing-in-itself than interestingness, which makes them seem simultaneously more durable. What is interesting is often fleetingly so. But this contingency confirms Ngai’s primary point: circulation matters to interestingness in a way that it doesn’t for other categories; a rose may be beautiful on the hundredth viewing, but even the most surprising one will not be interesting anymore at that point. Furthermore, interestingness “always register[s] a tension between the particular and the generic,” and thus “an object can never be interesting in and of itself, but only when checked against another: the thing against its description, the individual object against its generic type” (6, 26). How one categorizes the object matters. An item that is uninteresting if examined within a seemingly obvious genre or category may become considerably more interesting if placed (that is, circulated) into a less expected one. “I Will Always Love You” may be a great love song, for instance. But, given that it’s about a break-up, it would be an interesting choice to play at your wedding as the First-Dance song. Now, a genre is a virtual entity, of course, indicating similarity or analogy or family resemblance. It is constructed by ignoring distinctions among particulars and emphasizing shared elements instead. An item appears interesting, then, because it exhibits many elements of other things in its category or genre but not all of them; it seems to fit, but not too well.

As its name implies, the interesting bears a close relationship to interests—of those who might create interesting objects and also of those who might encounter them. Given that it registers difference among differences that make a difference, the interesting must be differently different; it cannot follow any sort of prior template. Nor can that which is interesting appear interested. Mikhail Epstein therefore argues, “What interests us deeply is interesting only to the extent to which it does not cede to outside interests. It grips us, rather than submitting to our desires” (85). The one hoping to interest another must exercise sprezzatura, appealing without pandering, seeming artful yet natural.

Considering interest as a factor in reception (i.e., interpretation or evaluation), Jan Mieszkowski suggests that “interest” is a slippery concept, referring both to what is “most proper to a person or group . . . the motivations or predilections that define an agent’s particularity” but also to “a dynamic that takes the self beyond itself” (112). Your interests, what you are interested in, are more “you” than anything else; they simultaneously define and produce you. And yet, because they draw you toward other things, they necessarily alter the you who is drawn. “In this sense,” Mieszkowski argues, “interest is always bound up with the possibility of things being other than what they are now” (114). Indeed, the etymology of the word interesting, drawn from the Latin words for “between” (inter) and “being” (esse), implies the potential for this internal schism. The question of the self is essential, therefore, to that of interest (112). This does not imply that all interests are self-interests, however. Rather, the interesting uniquely enables self-reflection: one contemplates one’s own ability to be (or become) interested. Subjective whims and preferences that might otherwise remain unconscious or un-interrogated become the object of exploration.

Aesthetic philosophers may attempt to deduce regular forms or features (e.g., smoothness, proportion, symmetry) that produce a given aesthetic experience (e.g., of beauty). However, the interesting is not subject to such regularity, given that difference (from what? and to what degree?) can only be determined situationally. “Anything can presumably count as evidence at one moment or another,” as Ngai notes (120). What should or does count as evidence of interestingness, then, is subject to deliberation, whether internal or interpersonal. Even argumentative premises demand justification, as do their own sub-premises and so on. It’s rhetoric all the way down. Because the pool of relevant criteria exists in constant flux, interestingness is neither fully provable nor fully falsifiable. Furthermore, as Ngai demonstrates, the assertion that something is interesting is as pedagogical as it is performative. In calling something “interesting,” one invites others to consider it. The object deserves more attention; it should be examined again, differently. Furthermore, when we declare an object interesting, we are “essentially making a plea for extending the period of the act of aesthetic evaluation” (170). Whereas other aesthetic judgments call attention to the thing being judged, the interesting diverts attention toward its own legitimation (169).

Whereas analyses of conventional aesthetic categories tend toward debate or agonism, investigations of the (purportedly) interesting operate via an alternate framework, enlisting the listener in conversation. Ngai argues that the interesting “redefines the process of aesthetic evaluation as including the other’s subsequent demand for us to justify it” (171). Furthermore, in such conversations, the original speakers typically conduct additional research about the thing in question—but not simply to become more persuasive in issuing their appeals. Rather, this process of recursive investigation and communication acts as a “way of enlisting [the listener] to convince us or help us arrive at a fuller understanding of why we thought the work was interesting to begin with” (171).[iii] Because the markers or criteria or causes of other aesthetic categories (e.g., the sublime and the beautiful) can seem settled, one may feel as though she knows the origin of her sensation. In contrast, the interesting is interesting precisely because its cause(s) seem(s) indeterminate, diffuse, or chaotic. In gesturing toward an interesting object in conversation, one implicitly says, “Help me figure this out; what is going on here?” It is a judgment about discursivity, supported discursively, which calls out for further discourse. Indeed, when one successfully interprets an impulse or assimilates the reasons she feels a given sensation, the object provoking that sense is no longer interesting per se. Rather, it is known and, in that way, possessed, domesticated.

Mark Dorrian, an architecture professor at the University of Edinburgh (Scotland), argues that “interesting” has become the “key term” within his discipline’s design studio pedagogy (173). When applied to student designs, it functions as a floating signifier, acquiring meaning mostly through intonation and attached adverbs: “interesting” meaning something quite different from “very interesting” (which is better) and “really very interesting” (which is even better still). As Dorrian notes, the renowned modernist architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe is often (though perhaps apocryphally) quoted as saying, “I’d rather be good than interesting” (qtd. in Dorrian 174). For Mies, an architect could be one or the other, but not both—and the former was certainly preferable. Now, it seems, the opposition between the two has been discarded, and the formerly excluded term now holds the place of dignity. (Somewhere the spectre of Derrida smiles.) It is better to be interesting than good. Likewise, to be uninteresting seems somehow worse than being outright bad (175).

While this analysis is informative, I am particularly intrigued by Dorrian’s argument concerning this transformation’s genealogy. He states in, of all things, a parenthetical aside: “We start to specifically value projects as ‘interesting’ whenever our normative understanding of what teaching is begins to become unstable” (176). The interesting has acquired value, then, because it “register[s] a kind of epistemological—and pedagogical—modesty, a doubt about the very possibility of final words and a recognition of the limits and partial nature of any claims that we might make” (177). Furthermore, it helps account for features that seem not to “fit” with the stated goals of the assignment but that simultaneously call into question un-stated suppositions and premises. In calling something “good” or “bad,” one implicitly affirms and upholds the validity of evaluative criteria. In contrast, an interesting work might be poorly executed but interestingly so, inasmuch as it “pos[es] questions back to the limitations of the criteria that it has failed to satisfy” (179).

Ngai similarly values the interesting as an evaluative criterion to be applied within literary criticism—hence her title’s assertion that it is an aesthetic category. Even so, throughout the course of her work, she repeatedly affirms its non-aesthetic qualities. Indeed, she notes its close connection to “the discursive presentation of proof or evidence for judgments made in explicitly non-aesthetic, concept-oriented contexts (science, history, religion),” and she further hypothesizes that “it might be internal to the interesting to toggle between aesthetic and nonaesthetic judgments” (117). That is, the interesting articulates a physical sensation and thereby enables quasi-objective, intellectual critique. In justifying her position, though, Ngai often replaces the term “aesthetic” with the term “affective,” or she uses the terms interchangeably, writing, for instance, “the evaluation of ‘interesting’ is always affective (however minimally or equivocally so)” (128). Elsewhere, she calls the interesting a “low, often hard-to-register flicker of affect accompanying our recognition of minor differences from a norm” (18). This slippage ultimately gestures toward one of its central features.

Affect theory is often complex and sometimes befuddling. So, for the sake of simplicity here, I will employ Lauren Berlant’s definition of affect: “The body’s active presence to the intensities of the present,” which still, crucially, “embeds the subject in an historical field” (“Intuitionists” 846). Affect is a nascent and indeterminate, collective sensation, as compared to emotion, which is (at least comparatively) definite or defined. For Ngai, the interesting is also characteristically undefined—and that is what makes it valuable. It is “a judgment based not on an existing concept of the object but on a feeling, hard to categorize in its own right, that in spite of its indeterminacy aptly discerns or alerts us precisely to what we do not have a concept for (yet)” (116).

Ngai argues that interestingness establishes “an affective relationship to the fact of our not knowing something.” In particular, it raises the question: “What was it that I must have noticed and simultaneously not noticed about the object in order to have judged it interesting?” (165).

Interestingness alerts us to our own conceptual lacks, letting us know that we feel something different or unexpected while reminding us that we do not have a framework for explaining how it differs from the norm we had anticipated (128). The interesting is “at once conceptual and non conceptual: conceptual in that some standard is clearly required for the perception of difference in the first place (different from what?); non conceptual in the sense that the concept for that perceived difference is affectively registered as missing” (131). In this light, we can understand one of Mieszkowski’s central claims: “To regard oneself as interested in something is to say that it may turn out to be less (or more) than one expects, but—and this is the key issue—the state of being interested is always the state of not yet knowing what one will get” (114). This indeterminacy may explain why the term itself, “interesting,” seems suitable to such a wide variety of cases—why we sometimes use it to refer euphemistically to things that were bad (e.g., “his decision to mix those ingredients was . . . ummm . . . interesting”) and at other times to things we actively enjoy (e.g., “that mix of ingredients was SO interesting!”)

Disinterest in Reddit’s “Today I Learned”: A Case Study

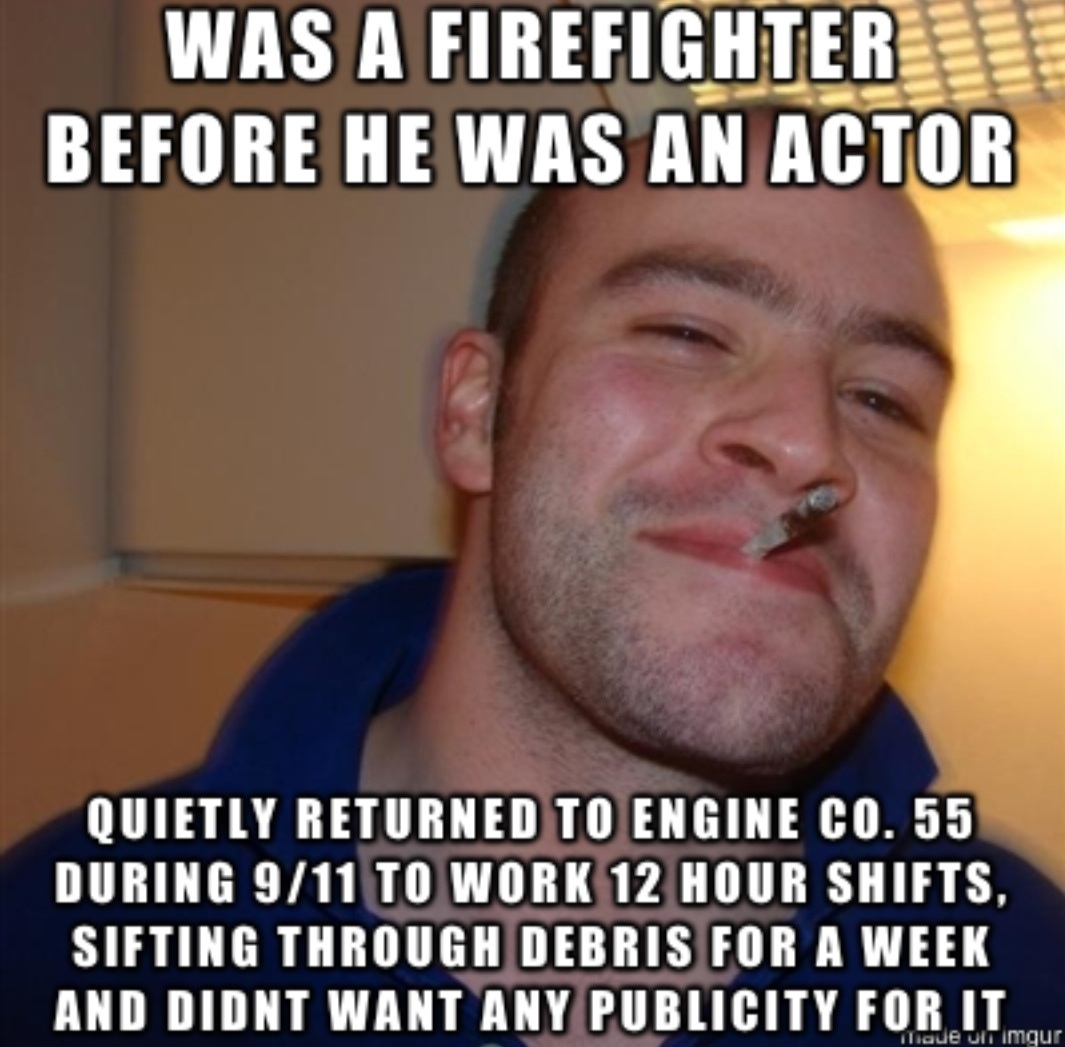

Please consider the following three facts. Number one: the research that established the Type A versus Type B personality categorization was funded by the tobacco industry, which hoped to demonstrate a link between mental make-up and heart disease and, as a result, to mitigate public outcry concerning the health risks of smoking (Petticrew, et al. 2018). Number Two: in the aftermath of the 9/11 Terrorist attacks, a famous actor who has appeared in films by the Coen Brothers, Tim Burton, Michael Bay, and Quentin Tarantino worked twelve-hour shifts as a firefighter, sifting through the rubble of the World Trade Center (Feldman). Number Three: the Hugo Boss company, now of fashion and fragrance fame, gained industrial prominence as manufacturer of Nazi SS and Hitler Youth uniforms (Govan). To be clear: none of these statements is intrinsically more interesting than any other. No fact ever is. Yet, among users of the discussion forum and aggregator Reddit, particularly its sub-Reddit (i.e., sub-forum) “Today I Learned” [TIL], one of them is substantially less interesting. Those users will not only find the second fact tedious; they may be appalled to be reminded of it, again, in a place they had hoped could be safe from this particular annoyance. They will also know the name of the actor mentioned in fact number two: Steve Buscemi.

In a sidebar to every page within the forum, TIL explains its purpose simply: “You learn something new every day; what did you learn today?” It invites its reader-users to “submit interesting and specific facts that [they] just found out (not broad information [they] looked up).” The distinction between “just finding out” a piece of information versus “looking it up” is crucial. TIL is a repository for information that users discovered unintentionally—or perhaps, for information that accidentally discovered interested readers. It is not a research aggregator; other sub-Reddits serve such a function. TIL’s basic premise is that what one person found interesting might also appeal to other users. In theory, it’s a starting point for information to enter into broad circulation, rather than merely re-circulating. In this way, it provides a test site for interestingness: in principle, things that are interesting should (and do) circulate and things that aren’t interesting shouldn’t. Of course, nothing is so simple in practice. Notably, the number of users subscribing to the forum is approaching eighteen million as of November 2017.

On September 24, 2009, a user named syuk created a TIL post entitled “The Day After the Sept. 11 Terrorist Attacks, Actor Steve Buscemi, Who Worked as a Firefighter from 1980-1984, Showed up at His old Fire Station to Help Out.” As far as I can tell, this is the first mention of this fact within the forum. The ensuing conversation, which contains forty-one archived comments, is generally positive, with users exclaiming, “Buscemi’s the fucking man,” “class act,” and “Right on Steve.” The rest of the discussion tends to involve references to his films, including The Big Lebowski and Reservoir Dogs. While one user, whose account has since been deleted, indicated that she or he may know how syuk learned this piece of information (and syuk seems to confirm that the user is correct), nobody implied that the fact was tedious or unworthy of conversation.

In line with the foregoing analysis, one might argue that this fact was found interesting, given its novelty within the TIL community; it had circulated into a new setting, and it differed from the other content already there. While affirming that position, I would also posit two alternate explanations. First, interests are idiosyncratic, akin to tastes, over which, as the Romans taught us, there is no accounting or disputing (de gustibus non est disputandum, after all). Or, in Mieszkowski’s phrasing, interests indicate “the motivations or predilections that define an agent’s particularity.” Even so, some things seem to be intrinsically more likely to engage interests than others. For whatever reason, for a lot of people (at least on the internet), Steve Buscemi is one of those things. In addition to TIL fame, he has been the subject of two of the most popular memes of the 2010s: Steve Buscemeyes (i.e., Steve Buscemi Eyes) and Hello Fellow Kids.[iv] Second, as Epstein notes, “The interest of a theory is inversely proportional to the probability of its thesis and directly proportional to the provability of its argument” (78-79). In this light, the least interesting theories do one of three things: “(1) prove the obvious, (2) speculate about the improbable without solid proof, or, worst of all, (3) fail to prove even the obvious” (79). Though a statement of fact is not a theory, a similar principle still applies. To some, Buscemi might seem an unlikely candidate for heroism, whether for spurious, skin-deep reasons (a Hollywood-ish belief that he doesn’t “look the part”) or simply because his on-screen personas so often shirk virtue. For instance, his best-known character, Reservoir Dogs’ Mr. Pink, infamously refuses to tip a diner waitress, despite intense prodding. But, at once, the fact of his 9/11 heroism is easily demonstrable via photographic evidence and first-hand testimonials. Thus, according to Epstein’s logic, such a statement would be interesting—though not intrinsically so.

Judgments concerning the “probability” of a fact will differ from person to person, of course, depending on their placement in information-circulation networks. Consider, for example, the proposition that time slows down the faster you move. For most of human history, that claim might have counted as interesting in the ambivalent (i.e., subtly negative) sense. If you affirmed it, you’d seem a little crazy. Later, as preliminary scientific evidence mounted, it might have been uninteresting, but less so: speculating about the improbable without solid proof. It would thus hit its peak of interest at a(n) (indeterminate) point between no evidence and overwhelming evidence. Today, if you told a physicist that you had an “interesting idea,” then proceeded to explain relativity to her, she would probably not remain interested very long. But, a seven-year-old sci-fi enthusiast might be amazed by it. Likewise, if one knew Buscemi personally, and thus understood his sustained commitment to public service, his heroism might seem predictable or obvious (i.e., highly probable) but not especially interesting. In contrast, his heroism would seem less “probable” the less one knows about Buscemi as a person. In a strictly statistical sense, the likelihood that any given person would have volunteered as an FDNY firefighter post-9/11 would be quite low after all. Interestingness emerges as an affective sensation as information circulates into new environs, and to the extent that it differs from prior information of (a) similar kind(s). However, whatever prior information is held as a baseline for judgment is itself also subject to circulation as well.

On September 25, 2010, almost exactly a year after the first mention, user Rageboxx submitted an entry, “TIL that Steve Buscemi Served for 4 Years as a Fire Fighter on FDNY.” This post, notably, made no mention of the actor’s post-9/11 return to service. But again the information was greeted warmly, though somewhat minimally. On December 19, 2011, the Buscemi TIL surfaced once more in a post from user ruff-20. At this point, the tensions at the heart of “the interesting” became apparent. Several users affirmatively exclaimed, “Good Guy Steve,” and “Is there anything this guy can’t do?,” and “TIL I love him even more now,” and “HOLY FUCK!, why is this the first time I’m hearing this?” Others discussed Buscemi’s life (with one claiming Buscemi as his or her “second uncle”) and contemplated the long-term health impacts afflicting 9/11 aid workers. A third group acknowledged seeing this information previously. One stated, “Ya I remember reading about this. He also declined any interviews that day” and another, indicating a sustained interest (or taste) for Buscemi, noted, “This has already been posted a bunch in TIL...but I give it an upvote every time.” At the same time, several veteran Reddit users expressed their frustrations. One lamented, “I haven't even been on Reddit that long, but this is the 3rd time I've seen this referenced. I guess you can never get too much of a good deed!,” and another sarcastically asked, “Today you learned??? obviously you have just joined reddit…” A third exasperated, long-time user attempted a joke, “TIL that every 3 days, someone new TIL’s this,” and a fourth, writing only the word “cool,” hyperlinked to search results for the forum “Today I Learned” and the search term, “Buscemi,” demonstrating a number of hits.

Devon Powers has recently investigated the sociological phenomenon of “firsties”—in which people rush to the comments sections of online articles simply to write “First!”—noting that it “dramatizes the importance of firstness as a central feature of cultural circulation” (166). While firsties are undoubtedly banal and frustrating, they tap into three intertwined value structures for valuing primacy: as ordinality (mathematical: first in line), historicness (temporal: first of its kind), and superlativity (evaluative: first-class) (168). People want to be first at anything, even the most bland, she argues, because being first provides a quasi-objective measure of uniqueness, and thus validity, and thus meaning. Though the facts shared on TIL bear considerably more informational content than firsties, they still follow the same basic cultural logic. A fact is most likely to be rewarded (that is, up-voted) upon first appearance. Therefore, because users compete for up-votes (and/or for the coin of the realm, Reddit gold, which has real-world monetary value), they are incentivized to circulate what they have learned immediately. In this way, the “Today” of “Today I Learned” both marks and produces its own presentism. Given the relatively large network of users engaged with TIL, a reasonable amount of “innocent” or “accidental” recirculation might be posited as the unavoidable “cost of doing business.” The comments quoted above indicate as much: one user suggests that someone who had learned this fact today “obviously…just joined reddit” and another adds, “TIL that every 3 days, someone new ’TIL’s this” (emphasis added). However, assumptions of innocence can only last so long. Eventually, everyone runs out of patience.

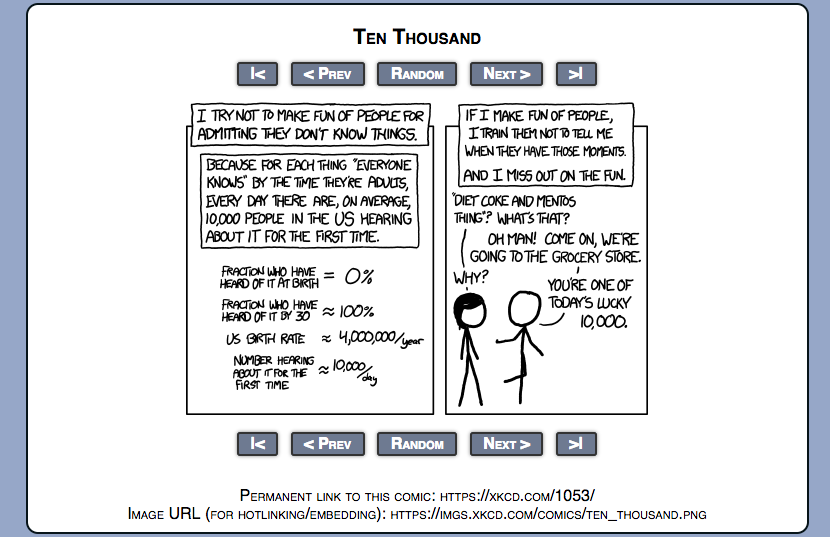

An important corollary follows: knowing trivial facts holds no inherent ethical value; it only entails having been found in some piece of information’s path of circulation. Though they can be a hostile and judgmental bunch, Reddit users will occasionally remind each other of this fact by recalling the “lucky ten thousand.” In a (reasonably) well-known installation of the web comic xkcd, which has now become a kind of cyber-proverb, one stick figure tells another:

I try not to make fun of people for admitting they don’t know things. Because for each thing “everyone knows” by the time they’re adults, every day there are, on average, 10,000 people in the US hearing about it for the first time. If I make fun of people, I train them not to tell me when they have those moments. And I miss out on the fun. (Munroe)

In principle, this comic seems to caution cynics toward restraint, to remind them that many instances of “common knowledge” are not actually held by all people—or, per my foregoing analysis, that interestingness is a function of one’s placement within information circulation networks. It can also serve as a reminder that everyone ultimately prospers from encouraging (or, not discouraging) the free flow of information; circulation forms social bonds. But, in practice, the comic’s message is often inscribed differently, as a means of defense for those who claim a lack of prior awareness. “It’s not my fault that I didn’t know this previously,” they claim, “But, today I got lucky to learn it, not by virtue of my own merits. And when you learned it, you got lucky too.”

For instance, on February 27, 2015 a Good-Guy-Greg-style meme referencing Buscemi’s 9/11 service appeared on a separate sub-Reddit, “AdviceAnimals,” with the title “GG Steve Buscemi. I Didn’t Know this About Him” (LittleDank). In response, several users would voice predictable responses: “I was wondering when I’d see this again,” and “Wow amazing tidbit, it only get’s posted 200 times a year on reddit,” and “Only the single most reposted article to /r/TIL of all time,” and “It’s like the most frequently posted TIL of all time.” But, amidst the hubbub, a notable exchange occurs. Like many others, user kevincreeperpants responded, in exasperation, “How many ways can we repost the Buscemi,” to which user crimson_05 replied, “So I take it you have never seen r/todayilearned?” Attempting to inject a sense of perspective, if not moderation into the exchange, user aravarth wrote, “I’m one of today’s 10,000,” thereby demonstrating an awareness of Reddit culture while still acknowledging ignorance on the Buscemi-9/11 point. Jumping to the defense of both aravarth and the original post [OP], user laddkemtonius exclaimed, “Repost police can suck it,” and Jessa_of_Caerbannog noted, “I never knew this OP and I’m subbed [subscribed] to TIL. Seriously I don’t know why people like to point out reposts so much.” User fluffyjdawg likewise asserted, “I’m on reddit quite a bit and never knew this. I don’t see the harm in reposts. Especially when they’re interesting.” In its own way, each side has a point in this argument, of course. Though frequent Reddit users may not actually be confronted by the fact as often as they claim, they are right to say that it has lost its interestingness to them, given the frequency of its circulation. Likewise, though fluffyjdawg may be wrong to argue that this fact (or any other) is intrinsically interesting, he has a point in defending those who were not previously counted among the lucky ten thousand.

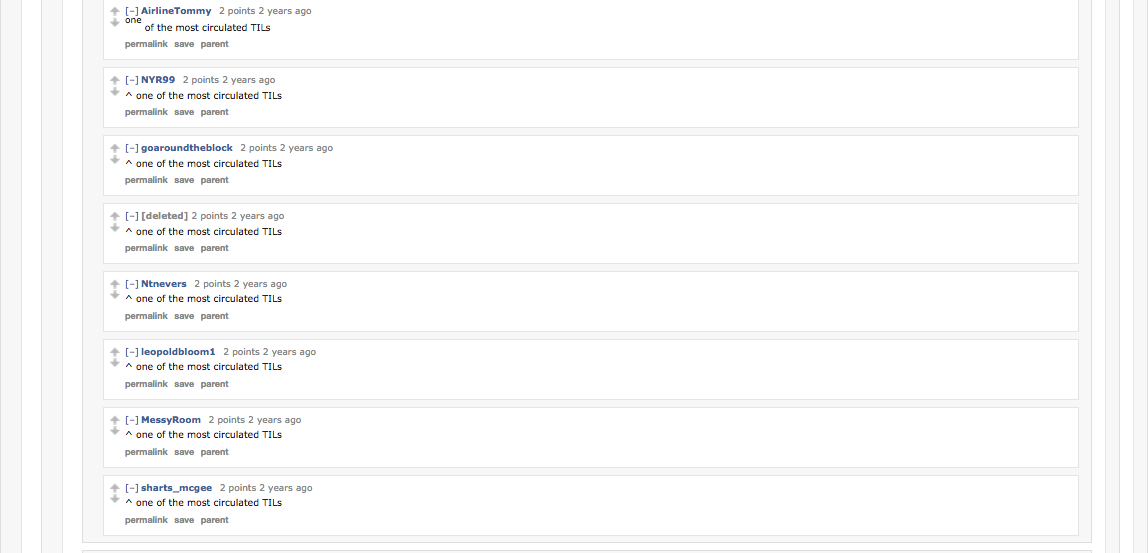

On March 23, 2015, only a few weeks after the GoodGuy Steve Buscemi debacle, the actual, living and breathing Steve Buscemi invited his fans to a Reddit Ask Me Anything [AMA] event (MrSteveBuscemi). This conversation, which further illustrates the d/evolution of the conversation, includes an exchange that might have been predictable to Reddit users, though much less so to Buscemi himself (an admitted internet novice). During the AMA, user Lord_of_Jam praised Buscemi for his service as a fire fighter and noted, “The photo of you volunteering after 9/11 is one of the best things I’ve ever seen,” before asking about his decision to become an actor. Following Buscemi’s earnest reply, chaos erupted. After user Theriley106 claimed, “Wow, TIL Steve Buscemi used to be a firefighter on 9/11. I’m going to make a TIL post about it,” user PurpleZeppelin replied, “Please don’t.” From there, another user (account since deleted) referred to the statements above as “^ one of the most circulated TILs.” Another user replied, “TIL the Steve Buscemi TIL is one of the most circulated TILs. I’m going to make a TIL post about it,” to which a separate user echoed: “Please don’t.” Another then replied, presumably referencing the meta-joke, “^ second most circulated TIL,” to which another could only concede, “TIL meta jokes are getting old,” and another, really beating the stake into the ground, replied, “TIL meta jokes are getting old, gonna make a meta post about it.”[v] At this point, a user named cottenball, attempting to inject some sarcasm, referred to the original idea of Buscemi as a firefighter as “one of the least circulated TILs,” but another user, AirlineTommy, was not having it.[vi] He replied, “one of the most circulated TILs,” at which point seven other unique users each replied, without interruption, “^ one of the most circulated TILs.” For these users, the fact of Buscemi serving as a firefighter had passed from the point of interest to frustration to resigned malaise. No joke or meta-joke or meta-meta-joke could improve the situation. The information had re-circulated too often to draw positive response.

Exercising their function as network gatekeepers, on April 6, 2016, the moderators of TIL requested identification of frequent TIL reposts, ostensibly for the purpose of banning or otherwise eliminating them (TIL Approved). The ensuing discussion referenced dozens of re-circulating threads, including facts regarding Napoleon Bonaparte’s actual height (not as short as you’ve been told), the cost of production for pennies (it’s more than one cent), and the existence of proteins named after Sonic the Hedgehog and Doctor Robotnik. The first repeat-offender mentioned there relates to Steve Buscemi’s service after 9/11. Two months later, on June 2, the moderators sent out another request, this time providing a list of ten already-banned topics, again topped by Buscemi-9/11 (TIL Approved!). Online trolls may still recirculate the fact in the future, but Steve Buscemi’s heroism has now been deemed officially uninteresting—in the sense that those aware of the fact now considered it banal, but in another way as well.

The interesting “always begins life as the judgement of those in the know,” but it does not end its life there. Rather, in-group members justify their claim to members of the out-group, which “in turn creates the occasion for one to supply them.” As a result, Ngai contends, “This aesthetic of and about circulation is actually aimed at enfranchising outsiders and thus expanding the boundaries of the original interest group” (172). Certainly, the in-group for TIL represents a finite subset of the world population. And, as previously observed, the forum’s guidelines stipulate that users share only those things they “just found out” accidentally, not anything they consciously attempted to learn. Thus, in principle, new information should flow from a lone individual to the in-group of forum users, then to an out-group of non-forum users. At that point, the impacted population could be quite sizable. However, the opposite is also true. As the topic at hand stultifies members of the in-group, the likelihood that outsiders will be enlisted decreases, particularly once a point of conversation is banned. Recirculating the same content over and over—or, in the case of Reddit, providing a space in which such content can continuously recirculate—can lead to the death of the discourse community: the size of the in-group constricts, fewer and fewer new members enter the conversation, and those within its bounds will become ever more inured to it. Any vibrant and enduring discourse—any that would continue indefinitely—must first be interesting. Those that are not will eventually become sedimented, encircled, echoing, then silent.

Conclusion

In The Cultural Politics of Emotion, Sara Ahmed provides a “theory of emotion as economy,” suggesting that emotion involves “relationships of difference and displacement without positive value” (45). She argues, “Affect does not reside positively in the sign or commodity, but is produced as an effect of its circulation,” and therefore, “signs increase in affective value as an effect of the movement between signs: the more signs circulate, the more affective they become” (45). Ahmed’s analysis does not imply that circulation inevitably leads to increases in positive affective value, however. She signals a generalized increase in intensity, instead. As signs circulate, they have a greater capacity to affect those encountering them, for good or ill. Indeed, the affective experience often becomes decidedly and increasingly negative—as with the proliferation of Buscemi-9/11 entries on Reddit. Historicizing contemporary connections between the rhetorical and the economic, Catherine Chaput makes a similar claim: “Rhetorical value has less to do with historical truth or a text’s inherent qualities and more to do with the circulation process” (14). And, she further reasons, “Affect moves through individuals vis-à-vis discourse, making them more and less energized . . . It can be life affirming, inspiring new actions, or it can be life constricting, sapping energy and limiting new possibilities” (15). Even the circulation of trivial facts, minor bits of information, can join groups together and increase their vitality, as with TIL, which ostensibly exists for this very reason. But that same circulation can drive communities apart or sap their energy, as also happens in actual TIL practice daily. At different times, the same piece of information (say, something about a firefighting actor) may do any or all of these.

Ngai admits that the interesting is “undeniably trivial.” Though she doesn’t pursue this reasoning, the interesting also seems to bear a peculiar connection to trivia, supposedly “meaningless” or “useless” facts. In many instances, trivial facts are indeed meaningless, insofar as “meaning” measures an alternate interpretation residing “beneath” the stated or obvious one. Likewise, many trivial facts are indeed useless, lacking direct application: you can know that Steve Buscemi was a firefighter without knowing what to do with that information. One might therefore justify trivia as valuable for its own sake—as pure, unapplied knowledge. But, even if it lacks utilitarian value, it may hold social value. Or, in economic terms: though it lacks use value, it may still have exchange value. For instance, over the last decade, bars hoping to generate extra business on weeknights have steadily turned toward trivia nights. And, if there’s anything to be learned from that trend, it’s that trivia acquires its social value through circulation, by transmitting positive affects and thereby producing social bonds. Why buy your friend a beer when you can tell her that the official state sport of Maryland is jousting? So long as a trivial fact remains interesting, it pulls people toward it and therefore, indirectly, toward one another. Nobody wants to go to trivia night where everybody knows all the answers (or none of them), though. The facts in question need to have circulated just enough but not too much. As Ngai suggests, that which is interesting must be “surprising—but not that surprising” (145). Ahmed argues that emotions do not circulate independently; instead, “the objects of emotion” do, and as those objects move they “hold us in place, or give us a dwelling place.” Therefore, she contends, “Movement does not cut the body off from the ‘where’ of its inhabitance, but connects bodies to other bodies: attachment takes place through movement, through being moved by the proximity of others” (11). Of course, no object is intrinsically interesting, and entropy exists within the system of circulation. Interesting objects decay. Eventually, they aren’t interesting anymore. And as the objects go, so go the bonds they produce.

Ngai argues that the interesting indexes information circulation, which, to be sure, it does. It also produces information circulation—obviously, in the sense that people share things that interested them, but in a more fundamental sense, as well. The interesting, in its role as an affective or aesthetic category, provides a linguistic stand-in for an indeterminate affective response, an incomplete judgment, a to-be-determined determination. But, more so than is commonly acknowledged, the question of what is or is not considered to be circulating is affectively determined. Ahmed writes elsewhere, “Things might appear fluid if you are going the way things are moving,” but, if you desire an alternate direction, then you may well “experience a flow as solidity, as what you come up against,” or “blockage” (On Being Included 186-87). Though Ahmed is concerned with decidedly non-trivial matters (regarding the practices and politics of institutional diversity), the fate of the Buscemi-9/11 fact illustrates her point effectively: it never really blocked or crowded out other content; it just felt like it did. It appeared, then re-appeared, then re-re-appeared (ad nauseam) on the TIL forum, circulating through each time. And yet, those who were not among the lucky ten thousand on any given day experienced it as blocking the overall flow of the system.

When it eventually resurfaces again, as it will despite the best intentions of the moderators, many will feel that they are stuck in a loop.

If it isn’t interesting, it feels like it isn’t circulating at all—though, of course, it is.

[i] In Our Aesthetic Categories, Ngai defines her eponymous term as “subjective, feeling-based judgments, as well as objective or formal styles” (29).

[ii] The interesting also bears relevance to scholarship on new materialism and distributed forms of agency. Ngai extensively quotes Isabelle Stengers and Bruno Latour, both of whom theorize agency as an emergent phenomenon, resulting from the chaotic coordination of an indeterminate number of human and non-human entities. According to Ngai, for Stengers, “interesting scientific propositions are those that associate the greatest and most diverse number of actors,” or what Latour might instead call “actants” (Stengers 85; Latour 131; qtd. in Ngai 114). Interestingness, then, is determined both by the number of things a statement accounts for and by its ability to connect actors/actants in its circulation.

[iii] Elaine Scarry suggests that “incit[ing] deliberation” is a defining feature of beauty, but her perspective differs markedly from Ngai’s about the interesting (On Beauty 28). Beauty causes an “impulse toward a distribution across perceivers,” akin to evangelism, unlike the interesting, which produces a desire for inquiry (6).

[iv] The Wikipedia of memes, http://knowyourmeme.com, dates the emergence of Steve Buscemeyes to April 2, 2011 and Hello Fellow Kids to the spring of 2012.

[v] Countless TIL posts indirectly reference Buscemi’s firefighting. Post titles include: “TIL that a Chemical Compound Made up of 2 Parts Hydrogen per 1 Part Oxygen is used as a Fire Suppressant by Firefighters such as the Famous Steve Buscemi” (mlp-34-clopper “Chemical”), and “TIL Famous NYC Firefighter Steve Buscemi has 3 Brothers Named Jon, Ken, and Michael” (mlp-34-clopper “Famous”), and, of course, endless variants of “TIL Steve Buscemi was an Actor” (e.g., m_lar).

[vi] In a fashion characteristic of Reddit norms, user t3hcoolness explains, “Superscripts are quite useful! actually I lied they are pretty much just used for comedic effect” (“How to use ^ superscripts on Reddit”). For other examples, see responses to t3hcoolness’s original post.

Ahmed, Sara. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Routledge, 2006. ---. On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life. Duke UP, 2012.

Berlant, Lauren. “Intuitionists: History and the Affective Event.” American Literary History, vol. 20, no. 4, Winter 2008, pp. 845-60.

Chaput, Catherine. “Rhetorical Circulation in Late Capitalism: Neoliberalism and the Overdetermination of Affective Energy.” Philosophy and Rhetoric, vol. 43, no. 1, 2010, pp. 1-25.

Dorrian, Mark. “What’s Interesting? On the Ascendancy of an Evaluative Term.” Architecture and Culture, vol. 4, no. 2, July 2016, pp. 173-84.

Edbauer, Jenny. “Unframing Models of Public Distribution: From Rhetorical Situation to Rhetorical Ecologies.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 35, no. 4, Oct. 2005, pp. 5-24.

Epstein, Mikhail. “The Interesting.” Qui Parle: Critical Humanities and Social Sciences. Translated by Igor Klyukanov, vol. 18, no. 1, Fall/Winter 2009, pp. 75-88.

Feldman, Lucy. “Steve Buscemi’s First Passion.” The Wall Street Journal, 4 Sept. 2014, http://www.wsj.com/articles/steve-buscemis-first-passion-1409853141.

Govan, Fiona. “Hugo Boss Apology after Nazi Links Exposed.” The Daily Telegraph, 22 Sept., 2011, pp. 18.

Gries, Laurie E. “Iconographic Tracking: A Digital Research Method for Visual Rhetoric and Circulation Studies.” Computers and Composition, vol. 30, 2013, pp. 332-48.

Latour, Bruno. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford UP, 2007.

LittleDank. “GG Steve Buscemi. I didn’t Know this AFbout Him.” Reddit, 27 Feb. 2015, http://www.reddit.com/r/AdviceAnimals/comments/2xelns/gg_steve_buscemi_i_didnt_know_this_about_him/

Mieszkowski, Jan. Labors of Imagination: Aesthetics and Political Economy from Kant to Althusser. Fordham UP, 2006.

m_lar. “TIL Steve Buscemi was an Actor Before Volunteering as a Firefighter on 9/11.” Reddit, 2 Apr. 2016, https://www.reddit.com/r/movies/comments/4cz19z/til_steve_buscemi_was_an_actor_before/?st=jfvd00vw&sh=8c63195a.

mlp-34-clopper. “TIL Famous NYC Firefighter Steve Buscemi has 3 Brothers Named Jon, Ken, and Michael.” Reddit, 1 Apr. 2016, https://www.reddit.com/r/todayilearned/comments/4cwl96/til_famous_nyc_firefighter_steve_buscemi_has_3/?st=jfvczgjn&sh=8a6f7965.

---. “TIL That a Chemical Coumpound Made up of 2 Parts Hydrogen per 1 Part Oxygen is Used as a Fire Suppressant by Firefighters such as the Famous Steve Buscemi.” Reddit, 1 Apr. 2016, https://www.reddit.com/r/todayilearned/comments/4cy0op/til_that_a_chemical_coumpound_made_up_of_2_parts/?st=jfvcyf4z&sh=67be10a3.

MrSteveBuscemi. “Steve Buscemi. AMA.” Reddit, 23 Mar. 2015, g. Accessed 10 Aug. 2016.

Munroe, Randall. “Ten Thousand.” xkcd, http://xkcd.com/1053/.

Ngai, Sianne. Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting. Harvard UP, 2012.

Petticrew, Mark P., Kelley Lee, and Martin McKee. “Type A Behavior and Coronary Heart Disease: Philip Morris’s ‘Crown Jewel.’” The American Journal of Publication Health, vol. 102, no. 11, Nov. 2012, pp. 2018-2025.

Porter, James E. “Recovering Delivery for Digital Rhetoric.” Computers and Composition, vol. 26, 2009, pp. 207-24.

Powers, Devon. “First! Cultural Circulation in the Age of Recursivity.” New Media and Society, vol. 19, no. 2, 2017, pp. 165-80.

Rageboxx. “TIL that Steve Buscemi Served for 4 Years as a Fire Fighter on FDNY.” Reddit, 25 Sept. 2010, http://www.reddit.com/r/todayilearned/comments/dimdm/til_that_steve_buscemi_served_for_4_years_as_a/

Ridolfo, Jim, and Dànielle Nicole DeVoss. “Composing for Recomposition: Rhetorical Velocity and Delivery.” Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, vol. 13, no. 2, Jan. 2009, http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/13.2/topoi/ridolfo_devoss/velocity.html

Rickert, Thomas. Ambient Rhetoric: The Attunements of Rhetorical Being. U of Pittsburgh P, 2013.

ruff-20. “TIL That Not Only Was Steve Buscemi a Firefighter, but on 9/11 he Went Back to His Old Station in New York to Work 12 hour Shifts Sifting Through the Rubble of the Twin Towers.” Reddit, 19 Dec. 2011, http://www.reddit.com/r/todayilearned/comments/nim5v/til_that_not_only_was_steve_buscemi_a_firefighter/

Scarry, Elaine. On Beauty and Being Just. Tanner Lecture on Human Values, Yale U, 1998.

Stengers, Isabelle. Power and Invention: Situating Science. Translated by Paul Bains, U of Minnesota P, 1997.

syuk. “The Day after the Sept. 11 Terrorist Attacks, Actor Steve Buscemi, who Worked as a Firefighter from 1980-1984, Showed up at his Old Fire Station to Help Out.” Reddit, 24 Sept. 2009, http://www.reddit.com/r/todayilearned/comments/9nhj7/the_day_after_the_sept_11_terrorist_attacks_actor/.

TIL Approved. “Request for Identification of Frequent TIL Reposts. Provide TIL Reddit Link as Top-Level Comment.” Reddit, 6 Apr. 2016, http://www.reddit.com/r/todayilearned/comments/4dnulc/request_for_identification_of_frequent_tils/.

TIL Approved!. “Request for Identification of Frequent TIL Reposts. Provide TIL Reddit Link as Top-Level Comment.” Reddit, 2 June 2016, http://www.reddit.com/r/todayilearned/comments/4m877s/request_for_identification_of_frequent_tils/.

t3hcoolness. “How to Use ^ Superscripts on Reddit. (Basic and Advanced Usage). Reddit, 10 July 2013, https://www.reddit.com/r/YouShouldKnow/comments/1i0nwv/ysk_how_to_use_superscripts_on_reddit_basic_and/?st=jfv6y6cn&sh=aaacddb8

Trimbur, John. “Composition and the Circulation of Writing.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 52, no. 2, Dec. 2000, pp. 188-219.