David Gruber, University of Nevada, Las Vegas

(Published August 24, 2022)

I have always been fascinated by name-calling. Unfortunately, this is not because I was any good at it, but because I was mostly on the receiving end. Growing up, my sister was ruthless. She hurled a relentless number of insults. “Reptile Boy” was her favorite. I don’t even know why. I never owned any reptiles. As far as I’m aware, I don’t look very slithery. But at some point in our troubled adolescence, I was any number of reptiles. I was also “Cretin,” “Slow-poke,” “Snot Face,” or “Ewy-goo.” I can hear her voice now: “Get out of my room, Reptile Boy!”

But name-calling is not all bad. In high school, I would be walking through the hallways, and someone would yell out, “Hey, Gruber! Good to see you!” My friends have always called me “Gruber,” “Goober,” or just “Groobs.” When you have a name like Gruber, hearing it out loud sounds a little like being called a name. But these are terms of endearment. (They are, aren’t they?) At my annual family reunion, all my crazy drunk uncles call me “Cub” or “Baby Bear” because my father’s nickname has always been “Bear.” Watching former President Trump carry his term through to the bitter end, I grew both in my distaste and appreciation for the power of name-calling.

We hear it all the time now. French President Emmanuel Macron calls U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson un clown and a gougnafier, a vulgar and useless lump of nothing (Miller). President Joe Biden was recently caught calling a reporter “a stupid son of a bitch” (News Wires). Former President Donald Trump, in particular, lobs insults like he’s in a frenzied game of darts, calling Michael Wolff a “total loser,” Senator Kirsten Gillibrand a “total flunky,” and Hillary Clinton a “nasty woman” (Blake).

Without overlooking the sheer quantity and force of Trump’s particular name-calling tendencies, we note that both sides of the aisle have historically dished insults. Scanning political history, it is easy to argue that name-calling is a time-honored political tradition. U.S. Presidential candidates make the point: George Bush, Sr. called Clinton “a bozo” and Trump “a blowhard” (Duffy and Gibbs; Staff). John McCain said Trump “fired up the crazies” (Hensch). John Kerry called George W. Bush “an idiot” (Reid). Further back in time, Abraham Lincoln was called “a barbarian” and “a yahoo” by those who opposed him (Bowden). In 1844, the Whig Party called Louis Cass a “pot-bellied, mutton-headed cucumber-soled” presidential candidate (Gabriel). So, that’s pretty much the whole range.

It’s not very pleasant to watch one adult call another a “sleaze-bag” or a “moron” or a “mutton-headed cucumber.” That kind of talk seems like it should have been abandoned in fifth grade. As we grow up, we learn that bad names hurt people’s feelings, and we should treat others as we want to be treated. That’s what Jesus said (Berean Study Bible, Matthew 7:12). Then, we grow a little older, and we learn that implying bad things about others or outright calling them dirty names crafts a logical irrelevancy called an ad hominem fallacy, which basically means that calling someone a “shithead” is a distraction from the actual argument—it simply does not address claims about, say, nuclear power or tax rates. But it raises the ears.

Democratic debates, we are told in university rhetoric and logic classes, require “good argumentation.” As Professor Christian Kock adamantly says, reasons need to be given for specific proposals, and debates should focus on each participant’s “counter-arguments and criticisms of proposed policies . . . and all these too must meet certain critical standards” (270). Unsurprisingly, calling someone a “shithead” does not meet those standards.

I’m not the first person to notice the political penchant for unpleasant words about opponents. Multiple commentators have bemoaned former presidents conducting verbal attacks (The Editorial Board; Kurtz; Schiff) with some arguing that it lowers the dignity of the office (Fulwood III) or harms the state of the democracy, which requires civil deliberation about what the country should do next (Feffer; Scarborough). Yet, somehow, none of those warnings have (yet) had much effect. Politicians continue to deploy ad hominem attacks, and arguably more and more in recent years. Indeed, watching the political arena today has spurred me to think more seriously about the role of ad hominem in rhetorical studies, how abusive forms of ad hominem, namely insults, relate to constructions of ethos, and whether there is ever a good reason, from the rhetor’s perspective, to fling a few ugly words at an opponent. I think there could be. And if you disagree with me, then you’re a mutton-headed cucumber.

In this paper, I hope to contribute to the conversation around abusive forms of ad hominem. I note first that they function as rhetorical strategies and, as Scott Jacobs rightly says, are therefore relevant to argumentation, even if altering the immediate topic. In like manner, ad hominems can sometimes spur civic discourse—as Douglas Walton has suggested (The Place of Emotion 23)—but I aim to also illuminate how they can more specifically create a contrast with an opponent in such a way that a trait, association, or personality quirk inherent to the opponent or linked to the opponent enters the debate. Beyond this, however, certain kinds of ad hominems also compel us, as rhetoricians, to peer outward to better see our audiences and consider the broader civic situation, since the verbal cut must also be acceptable to audiences, must appeal to those whom the rhetor desires to enchant, and must have specific cultural and symbolic resonances.

My focus here is the way that certain ad hominems accuse opponents in ways that tap into a shared pathos, or a charged political atmosphere that unites audiences. I aim to explore how such instances expose an overlap between ethos and atmosphere—and by “atmosphere,” I mean affective resonance at a time and place, like the felt “weather” of the event (e.g., Slaby)—that complicates traditional rhetorical descriptions of ad hominem. In fact, the link to wild, rowdy, or angry atmospheres alters how we usually imagine ethos exercised as a discursive construction that displays honesty, uprightness, goodness, and/or respect. I suggest toward the end of the paper that ad hominem links intimately to ethos, in part because of what audiences feel at a time and place and how rhetors draw upon those feelings; we must therefore not only consider the role of atmospheres when we teach about ad hominem but also ruminate on the ethical implications of turning to wallops and besmirches. Ethos and ad hominem are not only more nuanced than many would immediately expect insofar as they can both emerge from the rank and raucous side of human relations, but they are also more entwined with what Jenny Edbauer calls the broader “rhetorical ecology” than previously noted.

In brief, certain cunning, snide, and even bratty ad hominems, I argue, do not always operate as distractions but can compel deliberation on points related to the political sphere while showcasing the rhetor’s wit, perhaps making us chuckle, and performing the rhetor’s “good sense” (phronesis) or “good will” (eunoia) toward an audience, usually of friendly listeners who desire to be in on the joke. Accordingly, I argue that these negatively clothed, but positive (for the rhetor) forms of ad hominem are stylistically unique, and they function differently enough from other forms noted in the argumentation literature that they deserve a specific name. Although my feeling is that the term ad hominem may itself be a distraction to the rhetorical functions that I aim to describe, I take the road of least resistance here and propose the name Ad Hominem Light. The following discussion proceeds as follows: I review research on ad hominem; I then explore the definitional specificities of Ad Hominem Light, turning to a few political performances as case studies; I end with a consideration of the ethics of democratic deliberation and how we might include feelings and atmospheres in such discussions, specifically in reference to ethos and ad hominem.

The Reasoning of Ad Hominem

The abusive form of ad hominem is a power move. It is an oppositional exercise that creates a stark contrast with an interlocutor as much as it seeks to soil, roil, and troll. If trolling is the act of “starting quarrels or upsetting people by posting inflammatory or off-topic messages” (Hansen), then ad hominem attacks, although less elaborate and usually less sophisticated than trolling, also function to create the inferior and the superior. In the standard view, neither trolling nor ad hominem seek as a priority to build actual arguments. Instead, they function rhetorically to harm in some way the interests of the other and to get a rise out of them. And like trolling, the abusive ad hominem attempts to brand someone with a disrespectful or bad name (“dumbo,” “loser,” “moron”), harkening back to our childhood; it appeals to those adolescent playground instincts where we pick on others and find a way to skyrocket our popularity if we insult the other kid at precisely the right time. “Four-eyes!” “Momma’s Boy!” “Sissy Pants!” Ad hominem, we all learned at that age, can really hurt, but it can also create serious fans.

Ad hominem can increase the popularity of the rhetor because it functions in much the same way as constitutive rhetoric. “The Peuple Québécois,” as in Maurice Charland’s example of constitutive rhetoric, was supposed to constitute the identity and make the independence of the Quebec initiative more spreadable. Often the same general intentions motivate ad hominem attacks. If there is a difference at play, then the “calling forth” of the other person as X is something that embeds a character jab. It’s a character cutter. The rhetor becomes superior in calling out the name and constructs the Other as weaker or lower in the audience’s eyes. Consequently, audiences tend to get something like “The Devil” or “Billionaire Big Shot.” The first says that the person is evil and the second snobbish or disconnected from real life. The question lingering in the insult, for rhetoricians, is this: If politicians absolutely must appeal to their good character or goodwill, then why would ad hominem be off limits?

Just like some acceptable ethos appeals—such as “I have a good family” and “I love America”—are not necessarily admissible reasons to vote for someone but still par for the course, why would “He’s a bold-faced liar” or “She’s a devil worshipper” be relegated to the trash bin of the unacceptable? Indeed, we can even imagine an ad hominem that gets close to arguments happening in Washington, such as, “He’s a billionaire bigshot,” which is a sarcastic and maybe cunning way to say, “He doesn’t understand the middle class and has ties to big corporate interests.” Is this not a challenge to the other’s staged ethos and, thus, should be admissible? Or do we only call it ad hominem when we don’t like it?

I do not intend to forward an unqualified claim. I am not suggesting that all ad hominem deployments should be admissible, nor do all skillfully advance a rhetor’s position. Some ad hominems are way off-base, totally disconnected from any surrounding debate. Some are so ugly that they work against the person spouting them, like swinging nunchucks so hard that the dummy ends up hitting his own dumb face (yes, “dummy” is an ad hominem—but is it disconnected from the nun chucks case?). In fact, some ad hominem attacks, like “dummy,” can make us giggle; others are hard to hear and harder to take. But whether we giggle or sneer, when well-crafted, they do what they’re designed to do, in a context.

Ad hominems stick. It is hard not to meet a far-right U.S. campaigner who won’t utter the name “Pocahontas” when seeing Elizabeth Warren take the stage. And the media does not resist. They work these names into their headlines. NBC News, for example, printed the following after a 2020 Democratic Presidential debate: “Trump tells ‘Crazy’ Bernie Sanders: ‘Don’t Let Them Take It Away From You’” (Egan).

Communication scholars Kirsten Theye and Steven Melling argue that Trump’s use of common insults, such as “loser,” give him a stroke of authenticity. His merciless speech, they suggest, bolsters his campaign against “political correctness” so much so that his strident and bombastic style represents the endpoint or fulfillment of a “war against political correctness” (333). Rhetorical scholar Jennifer Mercieca calls Trump’s attacks “weaponized communication” that make him look like an aggressive free speech advocate and “a fighter” in a way that can then be defended, on his part, by rhetorically situating himself as nothing but a perfectly valid and skilled “counterpuncher” (275). Thus, it may be the case that Trump, precisely because of his political cachet and style, is able to lob insults at opponents at a much greater rate than more traditional politicians who have platforms based in policy reform or who aim to perform a rhetoric of unity, such as Obama’s emphasis on “Hope” or Hillary’s “Better Together.” That is to say, the proverbial leash of rhetorical vice can only be extended as far as the type of rhetorical dog sauntering into the political park to do some barking.

I am not arguing that ad hominem attacks work, per se, to further extend a politician’s support. That would be a difficult argument to make and probably require social scientific studies. But a starting qualitative assessment of ad hominem attacks suggests that demonizing a member of the opposition or, at minimum, expressing serious concern about the character of the other person can strengthen existing support. Indeed, it is worth considering that Donald Trump deployed ad hominem attacks from the outset of his election campaign and then won the election; he continued to release any number of slanders against those that he perceived as disloyal or disapproving, and his popularity at the end of his Presidency—after four years of repeating words like “loser,” “deranged,” and “crazed, crying lowlife” (Dopp)—stood at an all-time high in the summer of 2020.

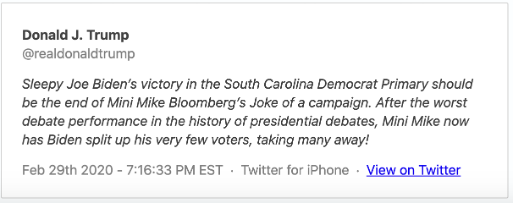

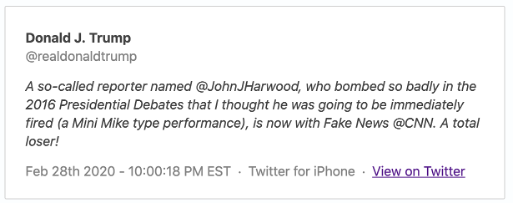

Certainly, former President Trump’s popularity cannot be directly attributed to his use of name-calling. There are so many other reasons why people have and continue to support him. But it nevertheless seems to be a primary communications strategy, therefore warranting some investigation. In fact, in a review of one hundred tweets from former President Trump starting from the day that I first sat down to consider his name-calling (February 28, 2020), I counted about fifteen ad hominem attacks on others. Of course, the exact number depends on whether you count tweets appearing on his timeline (retweets) or his personal tweets only. It also depends on whether you count disparaging remarks directed at a group, such as “Democratic Clown Show” (February 29) and exclude or include his indirect disparaging remarks, such as “the real politicians ate them [Tom Steyer and Mike Bloomberg] up and spit them out” (February 29). I did not count these. I only counted the obvious examples, such as when the President called CNN reporter John Harwood “a total loser!” (February 28).[i]

Figure 1

Figure 2

As rhetorical scholars, we could choose to see these ad hominems as another example of Trump’s manner of rejecting deliberation “as a communal goal” (Neville-Shepherd 175). That would position his ad hominems as another device creating what Ryan Neville-Shepherd calls a “post-presumption argumentation,” which cares nothing about truth but seeks only to stoke “conspiracy theorizing” (175). Joshua Gunn might here call Trump’s name-calling another form of “perversion” because Trump seems to get a rise from telling lies and subverting public discourse of mutual exchange (2-3). Yet, this assessment, as Gunn himself points out, does not also therefore mean that the ad hominems cannot participate in forging group solidarity and, indeed, are used to underscore a style of engagement that “expresses a particular worldview” (82). In that sense, ad hominems do help Trump, making him look like an honest rhetor to those also unable to contain a desire for “a newer order, new fundamentalisms” and to “call through all the crap” (Gunn 117). In staging stark contrasts with those who disagree, ad hominems become one way to oil up a political base’s self-confirming biases. But ad hominems can also intensify discourses about other candidates that can ignite deliberations and push toward conversations about their own wealth, patriotism, age, health, race, gender, and general civic judgement.

Ad hominems can be shaped to avoid reactions of revulsion amongst supporters (or undecided voters, for that matter) and stage a superior judgment. It is a matter of emotional management and unleashing just the right word for the context. As Patricia Roberts-Miller points out, many rhetors throughout the Enlightenment, and prior, were “not hostile to the emotions—but of a certain set of emotions (passions as opposed to sentiments)” (“John Quincy” 15). Emotions described as sentiments were seen as expressions beneficial to society and thus useful for constructing the rhetor’s ethos; however, passions relying on an “appeal to sympathy” might slip into “exhibitions of distress,” as John Quincy Adams noted (Roberts-Miller, “John Quincy” 15). In fact, John Quincy Adams himself, Roberts-Miller points out, used passionate emotions in his favor even if he claimed to believe that the “passions” were only weapons for self-serving party factions (“John Quincy” 16). Clearly, “dissent within certain parameters,” or emotional speech within acceptable bounds, proves highly effective, and Adams knew it. In fact, Roberts-Miller suggests that Adams turns to emotional speech precisely when he fears that he will not win through balanced rational argumentation (“John Quincy” 16).

Here, we come to a point: dispositions of mind and of the temper can be seen as virtues for audiences who read them as correct social judgements. Roberts-Miller’s work generally brings this out, especially when she examines attacks and condemnations designed to silence oppositions, drawing the conclusion that even when the attacks are obviously unreasonable, totally outrageous, ugly, and pernicious, some people will repost them and believe “that it made a valid point in a valid manner” (“Dissent” 171). However, we should be careful here and say not only “those people.” Skinnell and Murphy turn the discussion productively on ourselves, saying, “under the right conditions we all choose to step into the role of demagogue, willingly, happily—and without even needing to be convinced” (228). Because we all have in-groups and out-groups, strong senses of identity as well as instabilities, vulnerabilities, and values, any one of us could turn to demagoguery as effective means. Over-righteous, unscrupulous, polarizing, win at-all-costs rhetorics are, as Skinnell and Murphy say, “an ‘us’ problem,” but one that we should work to resist because that kind of speech conjures tribalism, sows distrust, rejects deliberation, and prefers insulation through aggressive forms over resolutions of socio-political anxieties through flexibilities (229-230). In a highly polarized society with deep emotions and resentments on all sides, what becomes most pertinent is to study the “real experience of public persuasion,” and this means pushing past “traditional explanations of expertise and authority” (Roberts-Miller, “Dissent” 172).

I agree; the effort of this article is to better understand the ways that speech, even disgusting and damaging speech, can function to inspire and unite, leading to rhetors on thrones and bringing audiences together. As I try to show in what follows, certain ad hominems are made palatable to multiple audiences through enrolling the fears and disdains that unite groups or through touching the specific social anxieties about an opposition’s personal deficiencies, however minor. Previously unauthorized “passions,” I suggest, can be transformed into acceptable “sentiments” by tapping into those awarenesses with a wink and giggle.

Ad Hominem Light

There is a specific type of ad hominem that Trump uses often, but I do not believe that he is the only one. I recall how Bob Dole used to call Jimmy Carter “Southern-fried McGovern” (Saletan), and people on both sides of the aisle used to call Bill Clinton “slick Willie,” a reference to his “unctuous salesman-cum-preacher mode” (Rozsa). I call it Ad Hominem Light. It is a form of association, stated playfully, sardonically, or comically, which under usual circumstances would not be offensive to the person on the receiving end but would rather be something more like a pet name or a term of endearment—yet once contextualized in a political debate, the name touches anxieties that an audience might have about politicians or more specifically about that person. Accordingly, Ad Hominem Light is designed to undercut key aspects of that opponent’s demeanor, personality, brand, and/or stance.

I could easily call my uncle “Crazy Uncle Ray” to his face, and he would probably smile with satisfaction. Likewise, after watching a co-worker doze off during a meeting, we might start calling him “Sleepy Paul,” and Paul is likely to laugh along. Former President Trump’s use of “Crazy Bernie Sanders” and “Sleepy Joe Biden” encodes, however, a slightly different effect; it functions through negative associations not as easy to simply laugh off. Although we could call our uncle “crazy,” the label, once applied in the current political context, aims to situate Bernie Sanders as unrealistic, underscoring how some see him as too zealous for his left-oriented democratic socialist stances. With respect to associations, the listener is then tempted (or more prone) to associate Bernie with the “mad scientist” figure who has crazy white hair and gets obsessed. Indeed, Trump later called Sanders “the crazy professor,” reinforcing the original association (see Chason and Itkowitz). Likewise, we could call our co-worker “sleepy” in a playful way, but in context, the term associates Joe Biden with his old age, a slow reaction time, and perhaps even a sort of absent-mindedness. The intended effect, then, is negative affective response and the intensification of conversations likely already detected by political operatives. The message aims to strike at precisely what some fear: that the opponent might not actually be fit for the office of the Presidency.

Yet, there is another effect. Little doubt exists that supporters of whomever generates Ad Hominem Lights do laugh. That is crucial to the “Light-ness” quality. At many campaign rallies, Trump gets roars as he doles out special names to Democratic presidential candidates: “Crazy Bernie,” “Mini-Mike Bloomberg,” “Sleepy Joe,” and “Pocahontas” (see Chason and Itkowitz). Each could be used, if situated differently, as a term of endearment. Thus, perhaps, because of each name’s “lighter” quality—lighter than “Idiot” or “Nasty Woman,” for example—the acceptability of laughing at and circulating these terms increases. The terms might also be understood as part and parcel of President Trump’s rhetoric of authenticity (Theye and Melling). In fact, Trump acts not unlike my bratty sister who looked me straight in the eye when I was ten years old, stuck out her sharp little tongue, made a “ssssthhhh, ssssthhhh, ssssthhhh” snake sound and then called me “Reptile Boy.” I was not amused. But her friends laughed.

Clip from Trump Rally

There’s no doubt that Trump can really lay into someone that he utterly despises. We have all seen him use unmistakably serious language. But looking through his tweets from 2020, one gets the overwhelming impression that most of the ad hominem attacks were Ad Hominem Light. They may be mean and certainly have the intention of discrediting the opponent and tend to ignore the specific argument at hand—that is, they are still formally ad hominem attacks—but they do not fit into traditional ad hominem categories.

Douglas Walton divides ad hominem into six categories (Ad Hominem Arguments 2-9). For brevity, I will list them here, putting his terminology in bold text and then using my own words next to simple examples of my creation, except where Walton is cited.

- Abusive, or “You’re a Dumb Jerk.”

“My political opponent is a terrible person!”

- Circumstantial, or “I Smell Something Fishy About That One.”

“He slinked away right before the vote on the house floor!”

- The Smoking Ad Hominem, or “That Person is a Damn Hypocrite.”

“Smoking kills, kid, so you shouldn’t do it,” and the kid quickly replies, “But you’re a smoker!” In this case, calling the person a smoker does not address the argument at hand about the effects of smoking, but it points out a “pragmatic inconsistency,” not a logical one, equivalent to calling the person a hypocrite (Walton, Ad Hominem Arguments 7).

- The Bias Ad Hominem, or “They Can’t Shoot Straight.”

“That judge is deciding on my coal policy? We all know that judge absolutely loves the coal industry!”

- Tu Quoque, or “They Do It Too (and Often Worse).”

“The politician that’s saying I take too much vacation takes vacation all the time, even going as far as Tahiti!

- The Genetic Ad Hominem, or “They’re Guilty by Association.”

“His best friend is a convicted criminal!”

Each could quickly be rephrased, tailored to sound like legitimate arguments. For example, if the politician takes too many vacation days and breaks the human resources rules, then perhaps that is a good reason to believe that she doesn’t always do her job or follow the rules. Likewise, if the argument regards someone’s voting record, then pointing out that a politician missed an important vote on the House floor would be reasonable. The overall question is: Does the statement address the argument, or does it distract with the introduction of slander or negativity?

In each of the six cases that Walton outlines, the example is mean, snarky, and negative. That proves a little distracting itself. Some ad hominems, once heard in context, may not stir us to look at the person next to us and cringe and, for the same reasons, may well be addressing arguments that an opponent makes in favor of her own ethos. The meanness of an ad hominem does not say much about its relevance or correctness, of course, but I argue that “lighter” ad hominems tend toward a point of relevance for audiences being addressed.

Walton admits to a special function for some ad hominems when he writes, “in some cases, at any rate, it would seem that emotional appeals like ad hominem and ad populum arguments are non-fallacious,” namely, when there has not been “a change from one concept of dialogue to another” (Ad Hominem Arguments 23, my emphasis). However, Walton never suggests that there could be a kind of ad hominem specifically geared to address an opponent’s ethos or one that is designed to be palatable to multiple audiences. This form would solidify the rhetor as funny or savvy while undercutting the opponent in a way immediately understood to have relevance to politics.

Here, we can remember that Garssen argues that ad hominems are not noticed at times because they “take on a reasonable appearance,” specifically when they seem to “mimic critical reactions” (207). But no one seriously thinks that “Crazy Bernie” or “Sleepy Joe” is mimicking a critical reaction or slipping past audiences in a disguise of reasoned argumentation. Thus, Ad Hominem Light does not appear well-described. It simply does not hide under a veil of reasonableness; we are more likely to note the insinuation in the suggestion as possibly reasonable, not the phrase itself, such as when the politician is not pretending to present a reason but only composing a contention put in frank terms that sounds familiar to people who talk without pretense. Thus, when we step back and review Garssen’s and Walton’s categories, we are compelled to ask: Where’s that kind of ad hominem? Where’s the half-slight bordering on the comedic?

Karina Korostelina categorizes various forms of “insults,” embarking on a sizeable Aristotelian-styled project of outlining six different types alongside of sub-types with functions fit to various political wars. Her book does not order insults in terms of ad hominem, per se, since she seems unconcerned with how much they distract from a running line of argument. She rather suggests that there are insults focused on the denigration of identity, justification for an action, protection of an in-group, denial of a right, extraction of power, and general delegitimization (Korostelina 2). Although she rightly notes that “insults and responses to them are culturally produced” (5), she asserts that “insults provoke violence and contribute to the worst conflicts in history,” consistently reading insults through a frame of “deeply frustrated” forms of protest, even though she recognizes humor sometimes plays a role (5-7). Her case studies—about murder, violence, and imprisonment—show how she is interested in the ultimate (possible) consequences but not too keen to rhetorically chart how insults sometimes slip through as lovely forms and bypass their own dynamics of offensiveness, bitterness, and slight. Again, we must ask, where’s the jokey branding that zeros in on the potential problem with the opposition’s ethos construction?

We could, of course, categorize a label like “Sleepy Joe” as the “denigration of identity” type of ad hominem (Korostelina) or as the “guilt by association” type or even the “circumstantial” type (Walton, Ad Hominem Arguments) because of the obvious insinuations being delivered. But “Sleepy Joe” and others like it feel qualitatively different. To my mind, what the rhetor is doing rhetorically does not fit perfectly into any of the above categories. Ad Hominem Lights may be associative in nature, but their rhetorical function is more nuanced. They play to the political cheerleading base and compel questioning in those still unsure where they fall politically, operating unlike the ad hominem attack on an opponent that is read immediately by many as contemptible. Ad Hominem Lights circulate like campaign buttons. “Crooked Hillary” is announced, and Trump’s supporters start saying it like it’s her real name. These kinds of attacks get in the brain. They surface around the edges of a smirk. They affect voters by infiltrating affects.

Ad Hominem Light constructs a theatrical frame for the opponents who then risk looking like clownish characters trying to perform in a political circus. And a theatre might be the most appropriate frame, since watching to see if “Crazy Bernie” will truly live up to the designation becomes another mode of popular entertainment. And maybe that is why we laugh (if we do), because we too often see political engagement in that way; it’s not real life, but more like reality TV. In this frame, Ad Hominem Light makes perfect sense. But what do our frames and acceptabilities suggest about the state of our own democracy?

I don’t want to venture down a road where I now try to argue that the political is a total spectacle pandering to consumer consciousness and a simmering skepticism born of corporate capitalist exploitation continually cutting back to increase profits and dominate new markets. That argument has already been made (Kaminski; van Elteren). What I want to say, instead, is that Ad Hominem Light alters political conversations, and this has something directly to do with its light quality. The name becomes a kind of playful or snarky mantra. And if it feels salient, then this is because it is chosen in such a way that the name matches inescapable qualities of the opponent, targeting for enhancement a negative perception of those qualities. For example, every time Bernie argues passionately—which he does often, and often very well—those unsure about voting for him have the potential to then think, “There he is—‘Crazy Bernie.’”

A more sophisticated name than Ad Hominem Light might be Contextual Ad Hominem, because the context determines the difference between the negative and the positive effect, being offended or being delighted. Indeed, a distinctive feature of Ad Hominem Light is that it is so “light” that knowing if it is negative or not must be a matter of the people, the place, and the timing involved. As Roberts-Miller says, it’s whether an audience understands the verbal volley as a sentiment and a legitimate concern or instead a desperate passion deemed delegitimate and despicable (“John Quincy” 15).

This brings me back to my sister. Reminiscing on my childhood, I wish that I had hung a sign on my bedroom door that read, “Keep Out: Home of Reptile Boy!” in big green letters. I wonder what she would have done. Or maybe I could have just adopted her little “ssssthhhh, ssssthhhh, ssssthhhh” snake sound and used it all the time. I bet that would have driven her crazy. She would have dropped it in a second. Reflecting on my childhood experience makes me wonder why “Sleepy Joe” doesn’t refer to himself that way or why “Crazy Bernie” can’t just embrace it and make a mad-scientist-themed video for his own Twitter feed.

The reason is probably twofold. First, these politicians recognize immediately that those branded names rouse the partisan base. The appeal is suited to preconceptions tailor-made for the most vivacious supporters. Thus, there is no need for the opposition to put effort into disarming the strategic intent of the name through an appropriation campaign. If Ad Hominem Light is contextual, then in “Sleepy Joe’s” case, Democratic voters are likely to see out from their own context, too, which means that they will probably comprehend that kind of name-calling as a childish or desperate attempt.

Second, appropriating the name would risk playing on the rhetor’s predesigned verbal battlefield. Helene Shugart argues that strategies of appropriation can be seen as a “reinforcement of existing oppression” possibly reifying oppressive forces more than actually challenging them (210-212). But Shugart also argues that the success of an appropriation is dependent on what is appropriated, who is involved, and how exactly the oppressive term or behavior is being appropriated. As she notes, adopting a label or a negative narrative can operate as a way to “empower” those who are oppressed by it, and this has affective benefits. But if the individuals on the receiving end do find a creative method to escape what is demeaning and exploitative, then they likely do so, Shugart argues, through reimagining the associated narrative, playing it out differently than intended, or undermining the central damaging connotation by embracing it as valiant or valued (210-212). I am reminded of my fat cousin Bobby’s big belly. When he rolls up his shirt at the family reunion, he acts as if he is a king even if people call him a slob; the belly is enrolled into a bodily appropriation of the various degrading names the other cousins use and is then not evidence of his gluttony but only of his glory.[ii]

However, I still have doubts that anything along the lines of appropriation would ever work with my sister. If I started making the little “ssssthhhh, ssssthhhh, ssssthhhh” snake sound, then she will probably just come up with something else, something worse. She’d start croaking like a frog. She’d call me “Frog-Face.” Then what? Am I really willing to go down an endless trail of attempts at (re)appropriating her vicious verbal inventions? More to the point: How could I appropriate that name if my voice actually did sound a little like a croaking frog? (It doesn’t, I don’t think.) Who is going to fight that kind of consistent, well-targeted conniving? Not me. And neither is Crazy Bernie.

Of course, there is one other option, outside of simply ignoring the Ad Hominem Light. That is: fight fire with fire. What if I called my sister “Barbie Girl”? I could zero in on her obsession with clothes and long hours spent in front of the mirror. (I told you I was never very good at name-calling but follow me here.) Everywhere she went, I could slink behind her chanting, “Barbie Girl, Barbie Girl, Barbie Girl.” I would make mocking hand gestures like I’m fixing my hair. Then, when she’s in the bathroom, I would yell, “Hey, Barbie Girl, hurry up!” When some boy called on the phone, I could yell out so that he could hear me: “Hey Barbie Girl, who is that jerk face on the phone?!” I’m dreaming now. Forgive me. The point is: I didn’t do that. But why?

I don’t know. Maybe I’m just a nice guy. I never wanted to throw insults. Or maybe I just knew I’d somehow always lose. See, I was the younger brother. The baby. The power dynamics were too entrenched. Better to be satisfied with Reptile Boy. That’s not so bad, right? Well, that’s what I decided, I guess. I learned how to disregard it and move on because ad hominems are always, even the “light” kind, attempts at hierarchical placement, which means that the target is perceived as encroaching, threatening, or more prominent, even if those perceptions are false. In other words, considering the power dynamics of ad hominems helps to expose perceptions and vulnerabilities. As a result, sometimes it is probably best to laugh along, sometimes to condemn it, sometimes to appropriate it, and sometimes to ignore it all together. The difference is a matter of context and atmosphere, i.e., a matter of what we hope to achieve in tandem with what we feel can be achieved at a moment when we scan those around us and see who is tempted to giggle and sneer.

Examining Ethos within an Ethical Frame

If my sister’s childhood insults were a mix of the playful and personal, then the ones that we hear so often today in the news are also always political, which means that the consequences stretch far beyond the family unit. But what can we, as citizens, do about Ad Hominem Light?

Perhaps the first thing we can do is what Kock suggests we need to do: ask ourselves, is the information that we get from politicians “accurate,” is it “relevant,” and is it “weighty” (281)? If not, we should discard it. The problem there, of course, is that it can be much too easy to say, for example, that Bernie might be a little “crazy” and that the information of his craziness is potentially accurate, and thus relevant and weighty. Discovering who can mediate “truth” in an era of “post-Truth politics” and “fake news” is a challenge by any standards, heavy in our present time, and one likely to give some advantage to name-calling and insinuations difficult to pin down (McIntyre). So perhaps more often than not, Ad Hominem Light will be deemed an acceptable form by the suspicious and the unsure. In this sense, Ad Hominem Light does not operate like the totally unacceptable ad hominem attacks that reveal themselves as repugnant. No, the “Light” attack can be disregarded, nothing more than a humorous observation, a silly side comment, a joke, really. In this, the ad hominem lingering in Ad Hominem Light can be denied if anybody asserts that the cut was unfair, immoral, or wrongly made. In addition, the Ad Hominem Light, as Gunn notes, makes visible the personality and style of the rhetor (82) even while it touches on the Other’s (potential) deficiency, presumably lending more reason to use it, especially if the chances of any lash-back are lower. However, there is a second question that we can ask of political speech, which Professor Kock also suggests to those of us advocating for deliberative democracy: “Is it for the common good?” (285).

Even if contributing to an argument about the opponent’s (possibly poor) character, and even if highlighting the rhetor’s wit or confidence, few would say that an abusive ad hominem spouted vehemently in a debate advances the common good. If only for not teaching our children bad habits and for supporting deliberations full of care and sympathy, the abuse cannot be deemed good. But is the circulation of Ad Hominem Light for the common good?

What good does the more palatable, more spreadable approach achieve? I have tried to argue throughout this essay that it makes people wonder, it infects and affects, it spurs conversation about otherwise simmering anxieties, and it crafts the rhetor’s own ethos. But still, it remains tough to say that it reliably contributes to the common good. Maybe a better question is simply: is it good? That’s a different kind of question than “does it work?” or “is it persuasive?” Is it ethical?

If we ask a question of ethics about the rhetor’s use of good reasons, such as, “He has no experience operating a budget or running a government,” or “Her tax plan will cost farmers more money,” then we are left only undoubtedly with: “Of course! It’s good and ethical to raise such points!” So, if Ad Hominem Light is not a distraction from the opponent’s argument, then must it be ethical as well? The two do not always correlate so easily. I can raise a relevancy unethically, such as by releasing relevant private health information without consent, just as I could make a claim that bears on a debate that ends up dehumanizing one group. But we should not dodge the core question: can we say that Ad Hominem Light is ethical and, thus, should be acceptable?

The answer to the above is messy and, perhaps not surprisingly, value driven. Those working for either party may argue that any attempt, even the crude or rude demonstration, wielded to secure power and to advance a (right or left) government needs to be deemed acceptable precisely because it works for what they see as the common good. As Roberts-Miller argues, “group identity and loyalty” may matter the most in politics today (“Democracy” 1); but “identity and loyalty” are not context-independent either. Loyalty and identity are both enwrapped in perceptions of the common good, at least in relationship to what is good for those inhabiting one’s own group, whether that be Evangelical Christians or atheist gun-owning libertarians. Importantly, lobbing an abusive ad hominem amid a debate—such as, “He’s just a fucking sleazebag!”—would likely never be totally acceptable because there is no clear way to understand the comment as achieving the common good. It far exceeds the normal social parameters. This is why Ad Hominem Light proves to be so powerful and persuasive.

Ad Hominem Light dodges the ethics board in being lightly made. It sounds like something that could be said at the family reunion, the barber shop, or the break room, outside of an explicitly political context. If Garssen’s special subterfuge ad hominem is mistaken for reasonableness, then the Light version is mistaken for acceptability. However, we should not miss the question, not “is Ad Hominem Light for the common good?” but: is it good? Is it ethical?

It is tempting now to return to Jesus’ golden rule: “Treat others as you want to be treated.” If that comes across as childish, then perhaps the feeling of childishness exposes just how buried in discussions of effect for particular audiences rhetorical studies has become. To argue for a deliberative standard based on a condition of mutuality (the “as you want to be treated” part) is not, to my mind, as childish or absolutist as it is derived from the concept of a democracy. If “as you want to be treated” is a statement about equality and one where all people get the same respect—the respect that we, so intimately, feel that we are due—then there is not much ethical wiggle room for Ad Hominem Light.

As a quip, a cunning Ad Hominem Light certainly builds an argument against an opponent’s purported competency, but it still carries along with it a denigration. It is not an argument about in/competency that can parade independently of mockery, cruelty, forgery, exploitation, or maltreatment. What I mean to say is: Those fucking idiots across the aisle keep using this thing called Ad Hominem Light, so it’s in our rhetorical best interests to not focus on ethics. Hell, I’m angry! And the rage streaming across my social media feed keeps firing me up! Here, I drive home a point: audiences, ethos constructions, emotions, and atmospheres are entwined with rhetorics.

Conclusion: Teaching Ethos and Ad Hominem as a Rhetorical Ecology

Ad Hominem Light suggests that rhetorical scholars must continue to re-evaluate how they comprehend and teach ethos. Two points are to be made.

First, ethos is not always neatly divided from logos and pathos, just as ad hominem is not always neatly divided from the classical rhetorical appeals. As Kristina Volmari puts it, the modes are “not clear-cut” because “there is overlap and room for interpretation” when facing any iteration of ethos, logos, or pathos (156). Presentations of facts, for example, show that one knows the facts, thus heightening ethos, whereas stating facts with conviction demonstrates passion, thus invigorating pathos, and so on. Many scholars already stress the non-independence of rhetorical concepts, but Thomas Rickert goes further; he argues that “rhetoricity is an always on-going disclosure of the world shifting our manner of being,” which is a way of saying that human agents engaging in verbal exchanges is only a half-story (xii). A linguistic-centric view of rhetoric is pancake flat, one equivalent to a side-show distracting from the whole ecological human-nonhuman picture of suasion happening through and in an “ambient” context of bodies, media platforms, social media systems, urban infrastructures, social services, financing regulations, and so forth (xii). Thus, Rickert can assert that “feelings are not an impediment to rational activity. Rather, they are fundamental” because they are living ties to environments and atmospheres (15).

Applying Rickert’s general idea to ethos: the prick of the cunning slight delivered with a sly look and a laugh assembles ethos out of the charged political atmosphere. In that atmosphere, audiences salivate for high drama, or want revenge. The ethos here is a pathos, but what hurts the heart is that the Other is demeaned while audiences cannot help but feel invigorated by the anger, sometimes even delighted, a feeling sparking the atmosphere and encouraging the spitting rhetor. So, how do we teach ethos? Is the concept compatible with a spiteful politician or a fiery face? Can we see ethos as constructed through a soundbite transformed into a biting meme?

I confirm Lynn Worsham’s idea that “our most urgent political and pedagogical task remains the fundamental reeducation of emotion” (216). As Julie Nelson argues, emotions in rhetoric “have not been adequately addressed” as rhetoric has experienced “a theoretical and practical divorce between ‘affect’ and ‘emotion’” (2). Although affect is typically taken to be immediate, autonomic, and associated with dispositions whereas emotions are enculturated and rationalized responses, Nelson points out that “they fuel each other” (3). But she says more: “we can (re)produce advantageous affects and emotions through mimesis in our bodies or media,” by which she means bodies not only use and feel rhetorics but become anew through them (4). It is a loop. Thus, the productive and pedagogical task is to find “new or counter relationships among feelings, images, and representations” so that “we can actively respond to harmful discourses and pedagogies of violence” (4). Megan Watkins says something similar, asserting that we must consider the “capacity of affect to be retained, to accumulate, to form dispositions and thus shape subjectivities,” and to engage rhetoric in light of such build-ups (269). Repetition in retweets, punctures of pleasure and pain, facial expressions symbolizing cynicism and outrage, postures of powerfulness and petulance, attitudes of superiority and stupor—everything entailed in making ethos and Ad Hominem Light—builds not only the rhetorical scene but future modes of deliberation and social relations. Future yous and mes are made in the process.

As a second, related, and final point, I want to underscore what may now seem obvious: that ethos can be constructed from negativity, not only from positivity. The point highlights how “beginning with emotion” complicates old rhetorical categorizations as much as it requires considering how atmospheres inform ethical evaluations (Nelson 5). In brief, flagrant uses of ad hominem attacks can solidify a rhetoric of authenticity in some cases, and in that way, they nicely fit the mold of traditional (and otherwise positive) examples of ethos said to work because they demonstrate Aristotle’s “good will” (eunoia), even if only toward the home audience, or display “good sense” (phronesis), if only about the opposing candidate (Aristotle). If we agree that ad hominem can demonstrate a politician’s goodwill toward an audience that dislikes the opposing party or that suspects something must be wrong with the other candidate, then we are saying that ethos is constructed through more than displays of positivity. At points, even the vile word can improve ethos before certain audiences. At that stage, we must think of ethos not only as generated from a broad ecology but as something needing to be enrolled also into an ethical framework, and probably one fitting to democratic deliberation where the goal is to uphold equality, improve dignity, and extend voice.

Traditionally, ethos has not needed much ethical scrutiny—because it has been principally about showcasing the great characteristics of the rhetor. The rhetor focuses on those traits that audiences already approve of and trust in advance of the debate (Halloran; Oft-Rose). If ethics ever came into consideration, it was about critiquing the over-amplification of virtuousness (Caza et al.). But as Ad Hominem Light demonstrates, constructions of “approval” and “trustworthiness” are not always easily identified as virtuous from the get-go. Ethos is sometimes strange and peculiar. Indeed, in the present era, name-calling holds a newly salient, maybe temporary seductive power and one tending toward aggrandization. After Trump’s successes, all kinds of rhetoricians, I am afraid, will be tempted to try it out. And it might just work. But we must ask: to what extent can ad hominem be used, like a knife, without cutting the heart out of the democratic tree? How long can a hollow tree stand? What can we say about the embodied, resonant rhetorical force without encouraging our students to revert to vilification and childish slander?

Here again, we must consider the ecology. If any form of ad hominem is made relevant or palatable through its connection to the simmering effects of a living environment, then contentious times with heightened polarization are likely, seems to me, to be the kind of environments that breed ad hominems. So, we can, as Nelson says, together reflect on the material and social conditions supporting the speech that we hear. And we can ask how ad hominem—even Ad Hominem Light—entrenches the sides. We must see that it contributes to a hardening of the political and social situation, making for ourselves a harsher and ultimately worse place to live.

The broader discussion illuminates how rhetoric sees itself not only as a functional discipline detailing responses but also one deeply concerned with responsibility.[iii] Thus, I suggest that we continue to move away from teaching ad hominem as a necessary irrelevancy functioning as a distraction to argumentation whose forms appear acceptable to audiences only when in “disguise” (Garssen). Similarly, we can choose to not situate ethos as shaped only from the glorious, virtuous, positive statements of rhetors talking about themselves in respectful terms but from what audiences are willing to swallow, not merely from norms that they are eager to praise.

The discussion further suggests that rhetorical scholar-teachers can resist marking ad hominem or ethos as discrete utterances acting independently—because they are not divorced from each other or from the vivacious affects that build up over time in an ecology and embed in civic discourse.[iv] We feel political speech acts in some specific kind of way because we sense the intricacies and alienations of the political atmosphere. We conclude with this: if we laugh now at the degrading joke about who should be respected or trusted, then surely it has already turned on us, and will be turning against us, since we confirm divisive speech as a laudable form of discourse when we rely upon democratic deliberation to stave off internal war and to treat us all as equally valuable. The irony, then, is that the Ad Hominem Light might spur more conversation about candidates’ weaknesses among some audiences, but it might also lead to the dampening of goodwill and to the rise of suspicion, the end of a conversation that could otherwise preserve each rhetor’s willingness to joke and to laugh together in unity.

[i] Tweets can be found on TheTrumpArchive.com

[ii] The name of my actual cousin has been changed to protect the innocent; however, the description could, in reality, fit any number of my family members.

[iii] Here I am attentive to Carolyn Miller’s 2018 call to rhetoricians to answer the question, “What of responsibility?” See: Walsh et al.

[iv] The language here might recall Jenny Edbauer, who says that the rhetorical situation “bleeds.” For discussion, see: Edbauer (9).

Aristotle. Rhetoric. Translated by W. Rhys Roberts. MIT: The Internet Classics Archive. http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/rhetoric.1.i.html.

Berean Study Bible. Infinity Concepts, 2016. https://berean.bible/.

Blake, Aaron. “’Nasty’ is Trump’s insult of choice for women, but he uses it on plenty of men, too.” The Washington Post, August 21, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/08/21/nasty-is-trumps-insult-choice-women-he-uses-it-plenty-men-too/. Accessed 16 July 2022.

Bowden, Mark. “’Idiot,’ ‘Yahoo,’ ‘Original Gorilla’: How Lincoln Was Dissed in his Day.” The Atlantic, June 2013, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2013/06/abraham-lincoln-is-an-idiot/309304/. Accessed 3 June 2021.

Caza, Arran, et al. “Ethics and Ethos: The Buffering and Amplifying Effects of Ethical Behavior and Virtuousness.” Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 52, 2004, pp. 169–178.

Charland, Maurice. “Constitutive Rhetoric: The Case of the People Québécois.” Quarterly Journal of Speech, vol. 73, no. 2, 1987, pp. 133–150.

Chason, Rachel and Itkowitz, Colby. “Trump mocks Democratic rivals, engages in name calling in rallying conservatives.” The Washington Post, February 29, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/trump-mocks-democratic-rivals-engages-in-name-calling-in-rallying-conservatives/2020/02/29/d137599a-5b07-11ea-...

Dopp, Terrence. “Trump Calls Omarosa a ‘Dog’ and a ‘Crazed, Crying Lowlife.’” Bloomberg News, 14 Aug. 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-08-14/trump-adds-dog-to-litany-of-omarosa-insults-amid-taping-feud. Accessed 3 June 2021.

Duffy, Michael, and Nancy Gibbs. “Inside the Surprising Friendship Between George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton.” Time, 4 Dec. 2018, https://time.com/5470205/george-hw-bush-clinton-presidents-club/. Accessed 12 December 2020.

Edbauer, Jenny. “Unframing Models of Public Distribution: From Rhetorical Situation to Rhetorical Ecologies.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 35, no. 4, 2005, pp. 5–24.

The Editorial Board. “Editorial: Stop the Name-Calling.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 16 July 2019, https://www.post-gazette.com/opinion/editorials/2019/07/16/Stop-the-name-calling-editorial-president-trump-tweets-opinion/stories/201907160044. Accessed 12 Dec. 2020.

Egan, Lauren. “Trump Tells ‘Crazy Bernie Sanders’ Don’t Let Them Take It Away From You. NBC News, 23 Feb. 2020. https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/2020-election/trump-tells-crazy-bernie-sanders-don-t-let-them-take-n1141206. Accessed 12 Dec 2020.

Feffer, John. “Donald Trump’s War on Democracy.” The Nation, 24 Sept. 2018, https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/donald-trumps-war-on-democracy/. Accessed 2 June 2021.

Fulwood III, Sam. “President Trump Has Cheapened the Dignity of his Office.” American Progress, 17 Feb. 2017, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/race/news/2017/02/17/426616/president-trump-has-cheapened-the-dignity-of-his-office/. Accessed 2 June 2021.

Garssen, Bart. “Ad Hominem in Disguise: Strategic Manoeuvring with Direct Personal Attacks.” Argumentation and Advocacy, vol. 45, no. 4, 2017, pp. 207–213.

Gabriel, Mac. “Ten Most Awesome Presidential Mudslinging Moves Ever.” Mother Jones, 31 Oct. 2008. https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2008/10/ten-most-awesome-presidential-mudslinging-moves-ever/. Accessed 23 June 2021.

Gunn, Joshua. Political Perversion: Rhetorical Aberration in the Time of Trumpeteering. U of Chicago P, 2020.

Halloran, Michael S. “Aristotle’s Concept of Ethos, or if not his Somebody Else’s.” Rhetoric Review, vol. 1, no. 1, 1982, pp. 58–63.

Hensch, Mark. “McCain: Trump ‘Fired Up the Crazies.’” The Hill, 16 July 2015, https://thehill.com/blogs/ballot-box/presidential-races/248232-mccain-trump-fired-up-the-crazies. Accessed 12 Dec. 2020.

Jacobs, Scott. “Nonfallacious Rhetorical Strategies: Lyndon Johnson’s Daisy Ad.” Argumentation, vol. 20, 2006, pp. 421–442.

Kaminski, Matthew. “This Political Spectacle.” Politico, 14 June 2016, https://www.politico.eu/article/this-political-spectacle-extremism-us-shakespeare-clinton/. Accessed 12 Dec. 2020.

Kock, Christian. Deliberative Rhetoric: Arguing about Doing. Windsor Studies in Argumentation, 2017.

Korostelina, Karina V. Political Insults: How Offenses Escalate Conflict. Oxford UP, 2014.

Kurtz, Howard. “Bush Gaffe Becomes Big Time News.” The Washington Post, 5 Sept. 2000, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/business/technology/2000/09/05/bush-gaffe-becomes-big-time-news/09b0d5fa-4660-4f9d-9598-038882d2e47d/. Accessed 5 March 2022.

McIntyre, Lee. Post-Truth. MIT P, 2018.

Mercieca, Jennifer R. “Dangerous Demagogues and Weaponized Communication.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 49, no. 3, 2019, pp. 264-279.

Miller, Jonathan. “How Will Boris Respond to Macron’s Insult?” The Spectator, 2 Dec. 2021, https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/emmanuel-macron-is-an-elite-level-troll.

Nelson, Julie D. “An Unnecessary Divorce: Integrating the Study of Affect and Emotion in New Media.” Composition Forum, vol. 34, 2016. https://compositionforum.com/issue/34/unnecessary-divorce.php.

Neville-Shepherd, Ryan. “Post-Presumption Argumentation and the Post-Truth World: On the Conspiracy Rhetoric of Donald Trump.” Argumentation and Advocacy, vol. 55, no. 3, 2019, pp. 175-193.

News Wires. “Joe Biden Caught on Mic Insulting Fox News Reporter over Inflation Question.” France24, 25 Feb. 2022, https://www.france24.com/en/americas/20220125-joe-biden-caught-on-mic-insulting-fox-news-reporter-over-inflation-question.

Oft-Rose, Nancy. “The Importance of Ethos.” The Journal of the American Forensic Association, vol. 25, no. 4, 1989, pp. 197–199.

Reid, Tim. “‘I Can’t Believe I’m Losing to this Idiot.’” The Times, 5 Nov. 2004, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/i-cant-believe-im-losing-to-this-idiot-hkdmmc7gvkh. Accessed 12 Dec. 2020.

Rickert, Thomas. Ambient Rhetoric: The Attunements of Rhetorical Being. U of Pittsburgh P, 2013.

Roberts-Miller, Patricia. “John Quincy Adams’s Amistad Argument: The Problem of Outrage; Or, the Constraints of Decorum.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 32, no. 2, 2002, pp. 5–25.

—. “Democracy and the Rhetoric of Demagoguery.” Patricia Roberts-Miller Blog, 10 Nov. 2018, http://www.patriciarobertsmiller.com/2018/11/10/democracy-and-the-rhetoric-of-demagoguery-odu-talk-hosted-by-rsa/. Accessed 14 Dec. 2020.

Rozsa, Matthew. “From ‘OK’ to ‘Let’s Go Brandon’: A Short History of Insulting Presidential Nicknames.” Salon, 7 Nov. 2021, https://www.salon.com/2021/11/07/from-ok-to-lets-go-brandon-a-short-history-of-insulting-presidential-nicknames/. Accessed 24 Mar. 2022.

Saletan, William. “The Dark Side: What You Need to Know About Bob Dole.” Mother Jones, Jan. 1996. https://www.motherjones.com/politics/1996/01/dark-side-what-you-need-know-about-bob-dole/. Accessed 29 March 2022.

Scarborough, Joe. “Trump’s Threat to Democracy.” The Washington Post, 31 Dec. 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/trumps-threat-to-democracy/2019/12/30/c8531bc8-2b2f-11ea-bcd4-24597950008f_story.html. Accessed 22 June 2021.

Schiff, Adam. “Trump’s Foes by Any Other Name.” The New York Times, 19 Nov. 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/19/opinion/trump-tweets-adam-schiff.html. Accessed 22 June 2021.

Shugart, Helene. “Counterhegemonic Acts: Appropriation as a Feminist Rhetorical Strategy.” Quarterly Journal of Speech, vol. 83, no. 2, 1997, pp. 210–299.

Skinnell, Ryan, and Jillian Murphy. “Rhetoric’s Demagogue | Demagoguery’s Rhetoric: An Introduction.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 49, no. 3, 2019, pp. 225–232.

Slaby, Jan. “Atmospheres—Schmitz, Massumi, and Beyond.” Music as Atmosphere: Collective Feelings and Affective Sounds, edited by Friedlind Riedel and Juha Torvinen. Routledge, 2020, pp. 274-285.

Staff. “George Bush Sr Calls Trump a ‘Blowhard’ and Voted for Clinton.” BBC News, 4 Nov. 2017. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-41871958. Accessed 12 Dec. 2020.

Theye, Kristen, and Steven Melling. “Total Losers and Bad Hombres: The Political Incorrectness and Perceived Authenticity of Donald J. Trump.” Southern Communication Journal, vol. 83, no. 5, 2018, pp. 322-337.

van Elteren, Mel. “Celebrity Culture, Performative Politics, and the ‘Spectacle’ of Democracy in America.” Culture, Politics, and Democracy in America, vol. 36, no. 4, 2013, pp. 263-283.

Volmari, Kristina. Half a Century of Forest Industry Rhetoric: Persuasive Strategies in Sales Argumentation. Vaasa: Acta Wasaensia, 2009.

Walsh, Lynda, et al. “Forum: Bruno Latour on Rhetoric.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 47, no. 5, 2018, pp. 403-462.

Walton, Douglas N. The Place of Emotion in Argument. Pennsylvania State UP, 1992.

—. Ad Hominem Arguments. U of Alabama P, 1998.

Watkins, Megan. “Desiring Recognition, Accumulating Affect.” The Affect Theory Reader, edited by Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth. Duke UP, 2010, pp. 250–68.

Worsham, Lynn. “Going Postal: Pedagogic Violence and the Schooling of Emotion.” JAC, vol. 18, 1998, pp. 213–245.