Jennifer Clary-Lemon, University of Waterloo

(Published November 10, 2020)

Martes americana atrata. Gulo gulo. Tyto alba. Clemmys guttata. Bufo cognatus. Danaus plexippus. Hirundo rustica. These are the names of our kin who are disappearing so swiftly that we barely got a chance to learn their names: American marten. Wolverine. Barn owl. Spotted turtle. Great Plains toad. Monarch butterfly. Barn swallow. As acknowledged by a recent UN-sponsored, intergovernmental body’s report on biodiversity, the rapid decline of these and other species—up to 1,000 times the historic rate (see Pimm et al.; Chapin et al.; Rands et al.)—is because of five major anthropogenic factors: climate change, human development, hunting and fishing, pollution, and invasive species (Diaz et al.). Of these five factors, human-based development tops the list as the greatest driver in species decline (Diaz et al. 12), though with any given species it is impossible to separate out one anthropogenic factor from another. As we recognize the destruction of species, we simultaneously legislate their decline by the production of conservation documents such as the Endangered Species Act [1] (in the US) and the Species at Risk Act or SARA (in Canada), which set specific guidelines for human-nonhuman interaction.

Such conservation action often reflects the invisibility of our natural systems’ complexity. As Robin Wall Kimmerer points out, we have arrived at such a state of crisis because of a long-standing bifurcation of nature from culture that allows contemporary humans to view themselves as somehow outside of nature and animals and plants as separate from culture (Tonino; see also Descola). Such a separation emerges as a Eurowestern phenomenon, which wholly disrupted and colonized the Indigenous worldview of the self as relationship with nonhuman others (Wilson 91). Although this commonplace is currently questioned by, for example, scientific studies in plant behavior (see Trewavas; Gagliano) and animal neuroreceptivity (see Braithwaite), as a Eurowestern guiding philosophy it still overarchingly governs human relationships with the land in terms of environmental management (Tonino). We are beginning to see this questioning echoed in contemporary theories of rhetorical ontology that stress “qualities of relations between entities, not just among humans, that enable different modes of rhetoric to emerge, flourish, and dissipate” (Stormer and McGreavy 3), as well as in rhetorical theory that challenges a prescribed hubristic role to the necessary anthropocentrism contained within conservation action (see Cryer). What is contained within the nature-culture distinction, then, is a quintessentially rhetorical problem: when humans cannot see themselves as part of the whole but rather a discrete and separate part, unconnected to nonhuman others, they can rationalize foregoing concern for anything that does not exist to support a mechanized, commodified, utilitarian view of a nature that exists only to benefit them. Yet we now live in a world of daily environmental disasters, extreme heat and drought, and rapid decline in biodiversity, a world in which all of these factors come down to the role humans play in activities that propagate climate change. In short, despite our best efforts, we are now living in a rhetorical problem that threatens all of our being-in-the-world. [2]

Given that species decline is happening at such an advanced rate, it is crucial that we work to think differently about the singular autonomy of human agency and the reliability of a human-centered rhetoric. We are in deep need of rhetorical models that embrace intraspecies entanglements (see Haraway; Tsing) as ways to help guide environmental governance by humans that will help slow species decline. Using a new material environmental rhetoric as a methodological framework, in this essay I suggest that human infrastructural engagements—specifically, those erected in service of mitigative, legislated acts of conservation—emerge as one way to make visible the presence of anthropogenic climate change and exemplify an entangled worldview that acknowledges the complicated presence of humans, nonhumans, and things as an intertwined moment and persuasive signifier on a landscape. Such infrastructural relations between the bodies of things, nonhumans, and humans function alloiostrophically—twist bodies’ attunements toward difference through a particular kind of contiguity—in ways that add rhetorical capacity [3] to human attentions. I turn specifically to species whose naturecultural entanglements of human-sponsored critical habitat force us to look more closely at the supposed divide between nature and culture. To do so, I examine infrastructural mitigations of Hirundo rustica, the barn swallow, legislated by SARA.

Rhetorical Bodies in Relation: SARA, Barn Swallows, Nesting Structures, and Something New

The barn swallow was listed as “threatened” on SARA in 2011 by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). [4] As one of four designations of species decline, threatened species are those who will likely become endangered “if nothing is done to reverse the factors leading to its extirpation or extinction” (Environment Canada) and are safeguarded through SARA’s federal legal protection. Between the time a species is listed on SARA and an action plan is developed that would apply to all provinces, each province creates individual plans to preserve at-risk species through particular legislation; in the case of Hirundo rustica, some of the most comprehensive action is legislated through Ontario’s Endangered Species Act (OESA).

Although barn swallows seem like a common enough species, in the last 40 years the species has seen a 76% decline in Canada and a 38% decline in both the US and Canada (COSEWIC v; Brown and Brown). Because these birds are seemingly abundant and present, they are not yet listed as endangered or threatened in the US despite their population decline by one-third in the last 30 years. However, I argue that one of the primary gifts the Hirundo rustica offers to us is that it has always been a closely intertwined, tandem species to humans, its population generally increasing with human development over time given its propensity to nest in human-made sites like its namesake barns, bridges, boathouses, sheds, and culverts (Badzinski et al. 2017). The barn swallow, as parallel species, offers us a reason to take notice. Thus, as citizen-scientist Robyn Bailey says of this particular species in decline, “something new is happening . . . there are factors other than habitat loss that are affecting barn swallows” (qtd. in Saulmon).

In drawing attention to that something new, I use a new material environmental rhetorical framework, which draws from a variety of material and affective theories to examine how persuasion moves in an affectual encounter of bodies (human, plant, animal, thing) on a landscape. Such a framework has three main guiding theoretical features: it acknowledges a flattening of the nature-culture divide by embracing the “underivable rhetoricity” of all bodies (Davis 536); it shifts attention from rhetorical actors to affective rhetorical bodies (plants, animals, things, humans) as sets of relations that draw our attention to how persuasion moves in an encounter; and it thus rejects the rational separability of the human from the nonhuman in rhetorical action to focus instead on how rhetorical energies circulate among bodies (Clary-Lemon 60-66). Put more simply, it offers a robust framework for considering how persuasion moves among humans and inanimate and animate matter along affective, agentive lines—how we are moved by nonhuman others. [5] Such a framework has its home among other contributions to the “new material” or “posthuman” turn; given this specific project’s situatedness among landscape, structure, affect, policy, and the nonhuman, then, it also finds good company with those working in geography (notably with non-representational theory; see Thrift), those in communication studies working with built environments that privilege “materiality, bodies, and movement” (Dickinson and Aiello; Blair, “Reflections”; Dickinson and Ott), and those working in environmental rhetoric who complicate simplistic approaches to management and conservation (see Rivers; Cryer; McGreavy et al.). To that end, the rhetorical bodies studied here are also those that are both materially embodied and discursively enacted.

Thus the rhetorical bodies in relation within this study are the populations of barn swallows in Canada, [6] SARA as legislated provincially through the OESA, and the SARA-mandated mitigative act of human-engineered barn swallow nesting structures (and thus the humans who design, engineer, and build them). Acting affectively within each of these bodies is the something new of climate change, quietly affecting some bodies more than others. I am particularly drawn to how each body here “produces suasion in and through its materiality” (Dickinson and Aiello 1296), offering in my analysis the takeaway of how human bodies may ultimately be convinced of the power of climate change: not by animal or plant kin and their disappearances, but instead by the capacities of material force and the stand-in of structures for species.

Entangled Beings: Affective Arguments, Persuasive Bodies, and Nonhuman Charisma

The barn swallow has had an intertwined and tandem relationship with humans. Known to live on every continent but Antarctica, before European colonization barn swallows nested in caves, holes, and crevices and have been recorded nesting on historic Native American and Canadian First Nations wooden structures (COSEWIC 9). Blue-bodied, red-throated, white-bellied, and easily cupped in the palm of a hand, barn swallows have been associated in myth and superstition with luck, protection, and healing, and have been said to carry magical stones of red and black in their bodies that, when placed under the tongue, are “able to sway people with . . . eloquence” (Webster 247). Barn swallows have thus benefitted both from human story and human development, today preferring to build their nests on almost exclusively human-made structures and rough surfaces, like wood, because mud (their primary nesting material) does not stick to smooth surfaces, like steel. A long-distance migratory bird and aerial insectivore, the barn swallow breeds and nests in northern locations before overwintering in southern, warmer climates. They are known to shadow large farm machinery for the insects such threshing evokes and thus often settle quite closely into domestic farming routines (Cocker and Mabey 316). Three notable embodied conditions—Jakob von Uexküll’s umwelt, as it were [7] —for the barn swallow are their close ties to human structural development, their susceptibility to temperature changes around breeding and migration times in the north (Saino et al.), and their dependence on insects as a food supply (particularly flies, beetles, moths, bees and wasps, and ants) to also affect nestling growth (McCarty and Winkler 286). The Government of Canada notes the species’ decline parallel along these lines in its species profile:

the main causes of the recent decline in Barn Swallow populations are thought to be: 1) loss of nesting and foraging habitats due to conversion from conventional to modern farming techniques; 2) large-scale declines (or other perturbations) in insect populations; and 3) direct and indirect mortality due to an increase in climate perturbations on the breeding grounds.

In other words, the other persuasive bodies that interact with the barn swallows, contributing to their movement across landscapes and their decline, are the small family farm (complete with barns) converting to the steel behemoths of industrial farm buildings, the decline in flying insect biomass reaching 75% in the last 25 years (Hallmann et al.), and weather in any given year remaining unpredictable. Each of these is predictably tied to climate change: the increase in Co2 emissions and pesticide use associated with large agribusiness (the second-largest emitter of global greenhouse gasses); the decrease in insect populations as a result of changing climate and land-use factors (see Fox et al.; Parmesan); and the shifting “climate envelope” of “temperature, precipitation, and seasonality” in any given ecosystem—rising global temperatures, extreme high and low temperatures, heavier precipitation in some areas and increased droughts in others, and increases in major weather events such as cyclones and typhoons—which severely affects a species’ ability to correctly time their life cycles with food supplies, increasing extinction risk (Thomas et al. 145; see also Blunden et al.; Cox).

Although the impact of weather on swallow bodies is severe—a cold snap might completely destroy nestlings—for humans, it operates differently. Part of what makes climate change so unpersuasive to humans is climate’s conflation with weather, or short-term changes in the atmosphere that make us feel something immediately in our bodies rather than a longer-term embodied remembering of weather over time in a specific area (climate). In human temporal-spatial bodies that only live up to 100 years in climate-controlled structures and are no longer confined to living in one area, climate change has very little immediate, suasive, bodily impact. Such a lack continues to underscore the naturalized nature-culture divide: if the climate is changing and we don’t (or barely) perceive it, it has little to do with us. Similarly, if humans perceive of insects as pests, then a 75% decline in insect biomass carries the affective capacity to encourage conversations about how nice it is to get bitten by fewer mosquitos and not how entire ecosystems rely on the delicate balance between predator-prey precipitated by insect bodies. If American farmers encounter barn swallows (still) nesting in their barns and delineate them as common or complain about them as pests, there is little room to convince them that the species overall is in decline. Small non-human bodies themselves, like insects or common birds, do not carry significant persuasive weight about species decline, whether they are absent or present. In Jamie Lorimer’s words, species like the barn swallow lack nonhuman charisma for humans, that quality of persuasive, affective being-in-the-world formed from both ecological proximity and corporeal—visual or textual—understanding (917-8). Compared to the iconic cuteness of the panda or the familiarity of the orangutan as endangered species, the barn swallow barely stands a chance.

The bigger picture of the decline of the barn swallow, much like climate change or the decline of other noncharismatic species, does not appear to be rhetorically heavy enough to persuade humans, despite our closeness with them. We might take, for example, the US Fish and Wildlife’s (USFW) non-classification of Hirundo rustica on the Endangered Species Act and the lack of such a petition as evidence for this proposition; after all, as a long-distance migratory bird, barn swallows cannot be confined to precise borders, particularly when northern climates are warming. To examine this rhetorical privation, I turn next to examining how nonhuman interventions of discourses and structure, specifically SARA and its OESA-legislated recovery strategies for habitat destruction, stand in and construct a different material-discursive argument about climate change and the decline of species with a different degree of intensity.

The Structural Manifestation of “at Risk”: SARA/OESA, Recovery Strategies, and Bird “Residences”

A legislative document since 2002, SARA governs the conservation of all endangered species in Canada. Although a bid was made to list the barn swallow on SARA as early as 2011, it was not until 2017 that Hirundo rustica was officially approved as a threatened species by Catherine McKenna, the Minister of the Environment and Climate Change. Once a species is listed on SARA, harming the species not only becomes illegal, but its habitat must be protected on any occasion where human development or encroachment might affect it—on both private and public land. Deemed “recovery strategies” or “action plans,” such mitigations take many forms and are legislated through provincial action until specific federal actions are listed on SARA (which as of this writing, the Hirundo rustica still does not have). These mitigative strategies are commonly invoked and undertaken in cases of human development (construction and demolition projects and infrastructure design) and can add millions of dollars to any design-build construction project. Applicable to all species on SARA, action plans include the research and monitoring of species, educational outreach, and the establishment of protected areas.

Although the barn swallow, as a migratory bird, has some protections under the Migratory Birds Convention Act of 1994, its listing on SARA both extends to critical habitat conservation and qualifies the barn swallow as an “individual” with a “residence,” or

a dwelling-place, such as a den, nest or other similar area or place, that is occupied or habitually occupied by one or more individuals during all or part of their life cycles, including breeding, rearing, staging, wintering, feeding or hibernating [s.2(1)]. . . . A residence would be considered to be damaged or destroyed if an alteration to the residence and/or its topography, structure, geology, soil conditions, vegetation, chemical composition of air/water, surface or groundwater hydrology, micro-climate, or sound environment either temporarily or permanently impairs the function(s) of the residence of one or more individuals . . . Under SARA, Barn Swallows have one type of residence: the nest. (Government of Canada, “Description of Residence” 1)

Under “damage and destruction of residence,” SARA lists moving, damaging, disturbing, or blocking access of a nest regardless of occupation. With this language, SARA shrinks the difference between nature and culture through a metaphor of sameness with its qualification of barn swallow nests as “residences,” though it lamentably asserts a false individualism to the birds, who settle in breeding pairs and are known to roost in groups up to 100,000 (Turner 48). Because barn swallows often commit to the labor-intensive build of over 1,000 flight returns to gather mud for just one nest, they also often return to the same nesting area for many years, only abandoning a nest once faulty or parasitic (Langlois). The destruction of a nest by human intervention, then, often means the loss of nestlings in any given year. Still, by the equation of nest with “residence,” we are softened by this common, uncharismatic bird with the entanglement of home.

SARA mitigations recognize that the main human threat to barn swallows lies with the overt destruction or tampering of habitat in the forms of residences/nests as opposed to the similar destruction of insect species or an impact on climate that affects species decline. This humanistic appeal to the conflation of nests with residences is a much easier action to practically legislate (to individuals and companies) than a wholesale attempt to stop or mitigate climate change. However, at least for the barn swallow in northern climates, the birds’ decline is a rather mysterious conflation—the additive or synergistic effects of changing human-modified habitat, prey availability and foraging habitat, and climate on a temperature-sensitive species. Much of the work to protect common species like the barn swallow, then, is done in areas of research and stewardship; however, I am interested in how SARA sets out barn swallow recovery strategies through OESA infrastructural recommendations of “best management practices” (Government of Ontario, “Barn Swallow Recovery”). I am particularly drawn to one specific material human-bird entanglement as mandated by OESA: “the design, placement and management of artificial nest structures to replace or enhance existing nest sites” (“Barn Swallow Recovery Strategy”), or the replacement of barn swallow mud nests with human-made nesting cups, and the replacement of traditional bird-preferred existing barns or bridges with artificial nesting structures. Although SARA legislates by similarity, I argue that such mitigations instead function alloiostrophically by making strange, allowing for persuasive entanglements characterized by incommensurability.

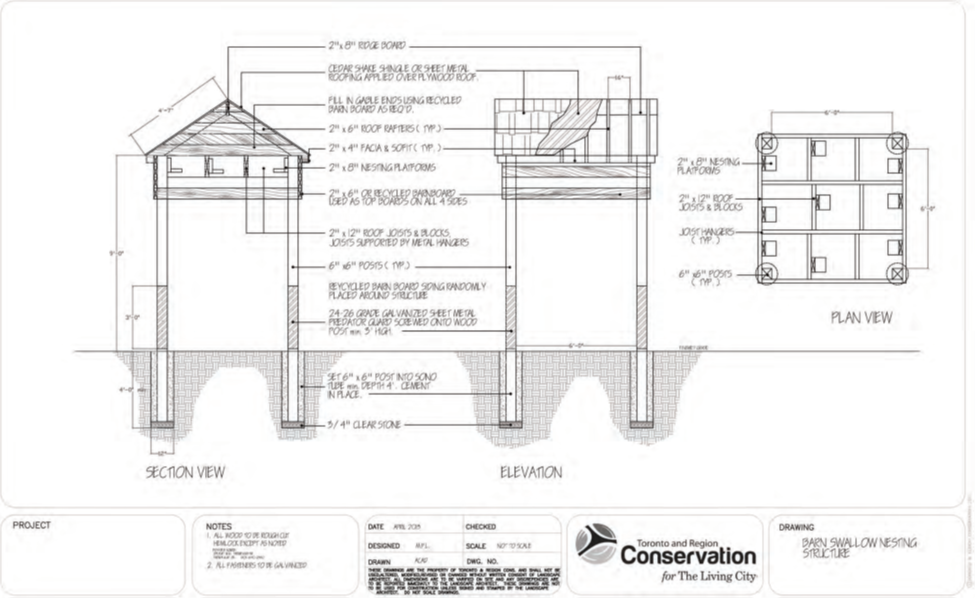

Although specific best management practices for species recovery vary provincially in Canada, most are similar in terms of critical stewardship, monitoring, research, communications, and management when it comes to a species who may cross provincial borders. Through OESA, Ontario provides specific how-to conservation manuals to build barn swallow nesting structures (Figures 1-3). A model from the Toronto Region Conservation Authority, Figure 1 shows that these structures must be built of specific swallow-approved materials (rough-cut hemlock, barn board, galvanized fasteners, cedar shake shingles), be of a specific height and dimension, and come with pre-installed nesting cups to lure barn swallows to this habitat.

Figure 1. Toronto Region Conservation Authority Barn Swallow Nesting Structure Plan (OMNRF 8)

Similarly, these discursive-material plans, such as Figure 2’s Nesting Structure Design, hearken to the description of SARA’s categorization of nests-as-residences with their inclusion of a “maximum privacy” option complete with vented gables and raccoon guards:

Figure 2: Nesting Structure Design by Morrison Hershfield with Ministry of Transportation (MTO) (OMNRF 10)

As recovery strategies, these contracted design plans are specifically tailored to SARA-mandated government regulations: for every nest destroyed, a nesting cup must be installed; for as much nesting habitat destroyed, a greater amount must be created; and the provision of “suitable nesting conditions” must be accounted for in the form of appropriate horizontal or vertical ledges, accessible entry, exit, and spacing, and sound structure that minimizes predation (OMNRF 2). Yet the finished products that arise out of these parallels, as Figure 3 shows, are not only less barn- or bridge-like (as any passerby would attest to), but also appear to the uninitiated to be a human-focused structural anomaly. For example, they cannot be climbed by children (as in other kinds of public equipment), they offer very little shelter (as in other kinds of gazebos), and they are not particularly aesthetically appealing (as in other kinds of “non-purposive” public art).

Figure 3: Barn Swallow Nesting Structure (OMNRF 2)

As barn swallow nesting structures emerge on the landscape, they exert a persuasive, illogical, and loud material agency, telling us something about the moment in which we are living and the creatures we are (or are not) living with.

Alloiostrophos: Substituting Structures for Species

Thus far, I have been naming the bodies in rhetorical relation to the decline of one particular species: the barn swallow, SARA as legislated by OESA, the humans who both cause and mitigate extinction, the changing climate, and the material structures that emerge on the landscape to try to preserve habitat. Whenever we see a nesting structure on the landscape, it is representative of a type of interspecies encounter grounded in an ecology of materiality, bodies, and movement (Dickinson and Aiello 1294). Within such an encounter, our attention might be drawn to how affects move among these bodies: swallow to climate, human to climate, swallow to human, human to structure, swallow to structure, human to swallow, swallow to SARA, SARA to human, human-swallow-climate-SARA-structure. In these and other additive encounters, what sticks to each is a kind of affectual suasion through bodily processes and movement, whether flying, nesting, foraging, or breeding (swallow); observing, reading, researching, building, reporting (human); standing, protecting, performing, deteriorating (nesting structure); legislating, confronting, authorizing, memorializing (SARA); moving, changing (climate). Given these actors, we might believe that we can control factors and mitigate them through the erection of separate structures based on an appeal of human-nonhuman similarity. At first glance, perhaps, there seems a logical, reasonable rhetoric at work here, just a cut-and-dried simple problem-solution format (if you build it, they will come).

However, this is a complex affective encounter. Despite the emergence of artificial nesting structures built to specifications, barn swallows do not prefer them and rarely use them, to the extent that researchers are using swallow decoys and sound recordings to attract the birds (“Barn Swallows and Social Cues”; Campomizzi et al.). Thus, what appears to be a simple solution based in equivalency is made far more complex by the energy of the encounter, the assemblage of actors, and the refusal of the barn swallow body: barn swallows are simply not persuaded by nesting structures in the same way that they are by barns, for whatever swallowy reason that rests in their bodies, memories, and preferences. This could be because barn swallows show high “colony fidelity,” or preference to reuse the same nests and nesting sites in a particular area, or that “in the vast majority of cases, an individual’s first site selection decision determines its lifetime breeding location” (Safran 122). Although barn swallows will move from nest to nest in one particular chosen location, it does not seem as though a simple substitution of one human-made structure for another works in all cases. This troubles both the idea of critical habitat—which we often associate with pristine wilderness, not cultural artifacts—and acts of conservation. It also, as Daniel A. Cryer suggests, draws our attention to the problematics of nonhuman withdrawal from being known or controlled, in many cases forcing humans to make “the best among a series of wrong choices” (465). It suggests that what we might gain from the erection of these structures is not a solution to an ecological problem, but a rhetorical understanding of nonhuman difference in a time of crisis.

Despite such mitigative failures, OESA still mandates the erection of nesting structures, and the evidence of their emergence is making its way into popular press discourse as an artifact of conservation (see, for example, “Barn Swallows Have”; Casey; “Barn Swallows Will”; “Search Engine”). In other words, these structures also exert a particular suasive force both for barn swallows and for the humans that build them. Yet this suasive force is so much more than a simple semiotic substitution: in the age of species decline, we know fundamentally that a nesting structure is neither a bird nor a barn nor a bridge. It is something, and this something garners a particular rhetorical power for humans even if, perhaps, it has less impact for swallows. Perhaps because of the wishes that we have for these structures to touch and appeal to bird bodies, they emerge as affectually sticky objects (see Ahmed, “Happy”), things that garner a power to attract a certain kind of attention or feeling.

To this end, I argue that unlike SARA’s focus on the commensurability of the human-nonhuman encounter, such built objects function alloiostrophically [8] —not as a metaphoric standing-in for something else, but as “an irregular turn motivated by a wish to take us to other possibilities in a way that would permit contact without catastrophe” (Sutton and Mifsud 228). We might view a nesting structure’s impact as a relational, agential body on the landscape wishing to make contact with the other through a particular kind of nearness and contiguity. To do so means to consider what their bodies do to others through sensorial, material communication: their mass, utility, durability, and tactility as well as how they affectually shape other bodies’ practices of movement (barn swallows) and observation, perception, and production (humans). Whether they succeed or fail, then, becomes less important than allowing structures to exist as a material rhetoric of peculiarity, a reminder of imperfect and illogical human inclinations “to make contact with the other” (Sutton and Mifsud 228).

Scholars in rhetorical theory, communication studies, and geography are noting the creative shift that paying attention to material sites, places, and spaces lends to rhetorical thinking (see, for example, Marback; Blair, “Contemporary”; Dickinson et al.). Concomitantly, non-representational theory is gaining ground in geography, and with it, an attention to the “onflow of everyday life” of humans and their surrounds, made up of material schema, practices, the vibrancy of things and their dispositions, and the role of affect and sensation (Thrift 5-12). This has given rise to scholarship that examines the role of material bodies such as sidewalks, water pipes, and buildings in city spaces, and how such assemblages encourage human movement, awareness, and feeling (Dickinson and Aiello 1296; McFarlane 162). However, such human-focused scholarship does not generally examine the role of nonhuman actors along with humans and things. As Sutton and Mifsud note, such public spaces lend themselves to patterning tropes of similarity and repetition, wherein the alloiostrophic “is configured in the idiosyncratic and particular lived reality of alterity” (229). Artificial nesting structures are neither built for human dwelling nor act as agentive city buildings (the way a post office or fire department might); unlike studies that look at how cityscapes organize (mostly) human movement, they are a rhetorically different animal. They do something by their presence on the landscape—remaking not the human body, but the swallow body, the swallow’s embodied preferences. Given barn swallows’ long, intertwined history with humans, nesting cups and structures to some degree “shape, constrain, and ultimately also mediate the everyday lives” (Dickinson and Aiello 1294) of Hirundo rustica in complex and unknowable ways that both maintain their alterity and allow a material point of contact. But what do they do to us?

For humans, nesting structures operate in a similarly affectually sticky way. Building these structures is a seemingly feel good act of conservation. They allow us to have some perceived sense of control over species decline in a way that, perhaps, is more satisfying than recycling or refusing a straw at a restaurant—and, as Cryer asserts, is perhaps better than any alternative. They help us make sense of a particular world in which species can be represented by structures and a rural bird-based structure can come to represent an opportunity for a “close encounter with wildlife” in much the same way that non-captive wildlife experiences do (like safaris or whale-watching) (Ballantyne 371). Nesting structures, with their heights of 10 feet, sturdy building materials, and puzzling non-utilitarian (for humans) features, give rhetorical weight to the nebulousness of species decline and climate change. Humans rarely listen to absences; the smallness of insect and swallow bodies, without the help of the swarm and the flight group, are not visible enough to provide the encounter that might tip the switch for climate action. Instead, we have OESA-mandated structures to stand in for a particular kind of proximity to threatened species, illogical monuments to climate change, structures that perhaps persuade by both their contiguity to barn swallows and humans and their embodiment of a particular kind of difference and attendant species withdrawal. Will we listen alloiostrophically to buildings in a way we will not listen to our animal and plant kin? Will we allow for their illogic, allow for swallows’ refusal, allow for our own failure, to exist all at once as one particular argument about the times we live in? Increasingly, these will be the questions that we must sit with as such interventions on the landscape become monuments to memories.

The gift that the swallows give to us is in their refusal: these structures stand as testimonials to humans getting it wrong in so many ways. Getting it wrong is, perhaps, the most important message we can possibly receive. It points to our incompetence in understanding the sophistication of the delicate systems of the planet. It points to our inability to perceive and to respond to the significance of nonhuman withdrawal, even at our most thoughtful and industrious. It points to the eminence of what we don’t and cannot know of the preferences located deep in the bones of bird bodies. It points to our desperate need for a new rhetoric of the nonhuman other. Most important, it points to the difficulty of separation, the impossibility of disjunction, and the futility of estrangement when a species has grown so very close to us.

Notes

[1] Note that incremental rollbacks of the American ESA are ongoing, As of August 2019, the US government now considers economic factors before including species on the ESA (Aguilera).

[2] As a copyeditor of this manuscript pointed out, not all humans are equally responsible for the times we find ourselves in. For a nuanced discussion of the origins of climate change in colonial capitalism, see Kathryn Yusoff’s A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None.

[3] Stormer and McGreavy draw on rhetorical capacity as an alternative to rhetorical agency, representing the latter as human-centered and the former as the potential for rhetoric to move within and among networked and enfolded systems by a number of nonhuman actors.

[4] As Favaro et al. point out, simply having COSEWIC assess a species does not ensure its placement on SARA. That must be determined by the Minister of the Environment and is based on COSEWIC assessments.

[5] This framework is informed by those in rhetorical studies working with rhetorical ambience (Rickert), Indigenous knowledge (Arola; Ruiz and Arellano), human-animal relations (Davis, Bjørkdahl and Parrish), rhetorical ontologies (Cooper; Barnett and Boyle) and ecologies (Edbauer; Greenwalt; McGreavy et al.). Such emergent rhetorical scholarship draws on a variety of interdisciplinary onto-epistemological theories that have helped shape them: political theories of things and the liveliness of matter (Bennett; Deleuze and Guattari) as well as new material feminist theory (Coole and Frost; Alaimo and Hekman), Indigenous new materialism (Ravenscroft, TallBear, Todd, Watts, Wilson), and affect theory that recognizes the ability of affect to travel among actors and bodies (Ahmed, Blackman, Brennan). For a discussion of the ways these ideas travel with and against Indigenous knowledges, see Clary-Lemon, “Ancestors, Gifts, and Relations: Towards an Indigenous (New) Materialism.”

[6] Notably, barn swallows are a long-distance migratory bird, and thus “in Canada” is taken only to mean their nesting habitat that is located seasonally there.

[7] Von Uexküll’s notion of the umwelt, or “around-world,” suggests that we understand animals and their worlds as a complete and inseparable whole (see Buchanan).

[8] In their discussion of alloiostrophos, from alloio- (otherwise/differently) and -strophos (turning/twisting/bending), Jane S. Sutton and Mari Lee Mifsud note that there is scarce historical record of this particular rhetorical trope, and they use it “as an invitation to theorize” (222) a new turn in rhetoric that resists metaphor (which privileges similarity) in favor of a model “where parts entering a whole do not lose their distinction but exist side by side within a unity” (227).

Aguilera, Jasmine. “The Trump Administration’s Changes to the Endangered Species Act Risks Pushing More Species to Extinction.” Time, 14 August 2019, time.com/5651168/trump-endangered-species-act.

Ahmed, Sara. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Routledge, 2004.

---. “Happy Objects.” The Affect Theory Reader, edited by Melissa Gregg and Gregory Seigworth, Duke UP, 2010, pp. 29-51.

Alaimo, Stacy, and Susan Hekman, editors. Material Feminisms. Indiana University Press, 2008.

Arola, Kristin. “My Pink Powwow Shawl, Relationality, and Posthumanism.” Panel Presentation on Perspectives on Cultural Rhetorics and Posthumanism. Rhetoric Society of America Conference, 1 June 2018. Address.

Badzinski, Debbie, et al. 2017 Best Management Practices for Excluding Barn Swallows and Chimney Swifts from Buildings and Structures. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, 2017.

Ballantyne, Roy, et al. “Conservation Learning in Wildlife Tourism Settings: Lessons from Research in Zoos and Aquariums.” Environmental Education Research, vol. 13, no. 3, 2007, pp. 367-383.

“Barn Swallows Have a New Place to Live Along Highway 401.” CBC News, 4 May 2016, www.cbc.ca/news/canada/windsor/barn-swallows-habitats-highway-1.3566966.

“Barn Swallows and Social Cues.” Bird Ecology and Conservation Ontario, 2015, www.beco-birds.org/portfolio-item/barn-swallows-and-social-cues.

“Barn Swallows Will Find New Homes at Hart Farmstead.” Guelph Mercury Tribune, 10 April 2013, www.guelphmercury.com/news-story/2796713-barn-swallows-will-find-new-homes-at-hart-farmstead.

Barnett, Scot, and Casey Boyle, editors. Rhetoric, through Everyday Things. U of Alabama P, 2017.

Bennett, Jane. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Duke UP, 2010.

Bjørkdahl, Kristian, and Alex C. Parrish, editors. Rhetorical Animals: Boundaries of the Human in the Study of Persuasion. Rowman and Littlefield, 2017.

Blackman, Lisa. Immaterial Bodies: Affect, Embodiment, Mediation. SAGE, 2012.

Blair, Carole. “Contemporary U.S. Memorial Sites as Exemplars of Rhetoric’s Materiality.” Rhetorical Bodies, edited by Jack Selzer and Sharon Crowley, U of Wisconsin P, 1999, pp. 16-57.

---. “Reflections on Criticism and Bodies: Parables from Public Places.” Western Journal of Communication, vol. 65, no. 3, 2001, pp. 271-294.

Blunden, Jessica, et al., editors. State of the Climate in 2017. American Meteorological Society, 2018.

Braithwaite, Victoria. Do Fish Feel Pain? Oxford UP, 2010.

Brennan, Teresa. The Transmission of Affect. Cornell UP, 2004.

Brown, Mary B., and Charles R. Brown. “Barn Swallow (Hirundo Rustica), version 2.0.” The Birds of North America, edited by Paul Rodewald, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2019, doi.org/10.2173/bna.barswa.02.

Buchanan, Brett. Onto-Ethologies: The Animal Environments of Uexküll, Heidegger,Merleau-Ponty, and Deleuze. State U of New York P, 2008.

Campomizzi, Andrew J., et al. “Conspecific Cues Encourage Barn Swallow (Hirundo Rustica Erythogaster) Prospecting, but Not Nesting, at New Nesting Structures.” Canadian Field Naturalist, vol. 133, no. 3, 2019, pp. 235-245.

Casey, Liam. “Inside Ontario’s Fight to Save Declining Barn Swallows, One Bird House at a Time.” Global News Canada, 4 July 2017, globalnews.ca/news/3574472/inside-ontarios-fight-to-save-declining-barn-swallows-one-bird-house-at-a-time.

Chapin III, F. Stuart, et al. “Consequences of Changing Biodiversity.” Nature, vol. 405, no. 6783, 2000, pp. 234-242.

Clary-Lemon, Jennifer. “Ancestors, Gifts, and Relations: Toward an Indigenous (New) Materialism.” enculturation, 12 November 2019, http://enculturation.net/gifts_ancestors_and_relations.

---. Planting the Anthropocene: Rhetorics of Natureculture. Utah State UP, 2019.

Cocker, Mark, and Richard Mabey. Birds Brittanica. Chatto & Windus, 2005.

Coole, Diana, and Samantha Frost. New Materialisms: Ontology, Agency, and Politics. Duke UP, 2010.

Cooper, Marilyn. The Animal Who Writes: A Posthumanist Composition. U of Pittsburgh P, 2019.

COSEWIC Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Barn Swallow Hirunda Rustica in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, 2011.

Cox, Amelia Robin. Population Decline in an Avian Aerial Insectivore (Tachycineta Bicolor) Linked to Climate Change. 2018. Queen’s University, MS Thesis. qspace.library.queensu.ca/bitstream/handle/1974/24866/Cox_Amelia_R_201709_MSC.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y.

Cryer, Daniel A. “Withdrawal without Retreat: Responsible Conservation in a Doomed Age.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 48, no. 5, 2018, pp. 459-478.

Davis, Diane. “Autozoography: Notes Toward a Rhetoricity of the Living.” Philosophy and Rhetoric, vol. 47, no. 4, 2014, pp. 533-553.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus. 10th Printing. Translated by Brian Massumi, U of Minnesota P, (1987) 2003.

Descola, Philippe. Beyond Nature and Culture. U of Chicago P, 2013.

Diaz, Sandra, et al. “Summary for Policymakers of the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, Advanced Unedited Version.” Report of the United Nations IPBS, 6 May 2019, www.ipbes.net/system/tdf/spm_global_unedited_advance.pdf?file=1&type=node&id=35245.

Dickinson, Greg, et al., editors. Places of Public Memory: The Rhetoric of Museums and Memorials. U of Alabama P, 2010.

Dickinson, Greg, and Giorgia Aiello. “Being Through There Matters: Materiality, Bodies, and Movement in Urban Communication Research.” International Journal of Communication, vol. 10, 2016, pp. 1294-1308.

Dickinson, Greg, and Brian Ott. “Neoliberal Capitalism, Globalization, and Lines of Flight: Vectors and Velocities at the 16th Street Mall. Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies, vol. 13, no. 6, 2013, pp. 539-535.

Edbauer (Rice), Jenny. “Unframing Models of Public Distribution: From Rhetorical Situation to Rhetorical Ecologies.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 35, no.4, 2005, pp. 5-24.

Environment Canada. “Species at Risk Fall into These Four Categories.” Government of Canada, 2019. https://www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/D5CEFC12-E936-4FDD-94BE-6D56846739AB/poster_0408-eng.pdf

Favaro, Brett, et al. “Trends in Extinction Risk for Imperiled Species in Canada. PLoS ONE, vol. 9, no. 11, 2014, pp. 1-8.

Fox, Richard, et al. “Long-Term Changes to the Frequency of Occurrence of British Moths are Consistent with Opposing and Synergistic Effects of Climate and Land-Use Changes.” Journal of Applied Ecology, vol. 51, 2014, pp. 949-957.

Government of Canada. Species at Risk Act (SARA). Justice Laws Website, 12 December 2002, laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/s-15.3.

---. “Description of Residence for Barn Swallow (Hirundo Rustica) in Canada.” Species at Risk Act Public Registry (Residence Descriptions), May 2019.

---. “Species Profile: Barn Swallow.” Species at Risk Public Registry, 29 November 2011, wildlife-species.canada.ca/species-risk-registry/species/speciesDetails_e.cfm?sid=1147.

Government of Ontario. “Alter a Structure (Habitat for Barn Swallow).” Species at Risk, 26 April 2019, www.ontario.ca/page/alter-structure-habitat-barn-swallow.

---. “Barn Swallow Recovery Strategy.” Species at Risk, 9 May 2019, www.ontario.ca/page/barn-swallow-recovery-strategy.

Greenwalt, Dustin A. “Toward a Rhetorical Ethology.” In Bjørkdahl and Parrish, pp. 109-128.

Gagliano, Monica. “The Mind of Plants: Thinking the Unthinkable.” Communicative and Integrative Biology vol. 10, no. 2, 2017, dx.doi.org/10.1080/19420889.2017.1288333.

Hallmann, Caspar, et al. “More than 75 Percent Decline over 27 Years in Total Flying Insect Biomass in Protected Areas.” PLoS ONE, vol. 12, no. 10, pp. 1-21.

Haraway, Donna. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke UP, 2016.

Langlois, Annie. “Barn Swallow.” Hinterland Who’s Who. 2015, www.hww.ca/en/wildlife/birds/barn-swallow.html.

Lorimer, Jamie. “Nonhuman Charisma.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, vol. 25, no. 5, 2007, pp. 911-932.

Marback, Richard. “Detroit and the Closed Fist: Toward a Theory of Material Rhetoric.” Rhetoric Review, vol. 17, no. 1, 1998, pp. 74-92.

McCarty, John P., and David W. Winkler. “Relative Importance of Environmental Variables in Determining the Growth of Nestling Tree Swallows Tachycineta bicolor.” Ibis, vol. 141, no. 2, 1999, pp. 286-296.

McGreavy, Bridie, et al. Tracing Rhetoric and Material Life: Ecological Approaches. Palgrave, 2018.

McFarlane, Colin. Learning the City: Knowledge and Translocal Assemblage. Blackwell, 2011.

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (OMNRF). Creating Nesting Habitat for Barn Swallows, Best Practices Technical Note Version 1.0. Species Conservation Policy Branch, 2016.

Parmesan, Camille. “Ecological and Evolutionary Responses to Recent Climate Change.” Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, vol. 37, no. 1, 2006, pp. 637-69.

Pimm, Stuart L., et al. “The Future of Biodiversity.” Science, vol. 269, no. 5222, 1995, pp. 347-50.

Rands, Michael R.W., et al. “Biodiversity Conservation: Challenges beyond 2010.” Science, vol. 329, no. 5997, 2010, pp. 1298-1303.

Ravenscroft, Alison. “Strange Weather: Indigenous Materialisms, New Materialism, and Colonialism.” Cambridge Journal of Postcolonial Literary Theory, vol. 5, no. 3, Sept. 2018, pp. 353-370.

Rickert, Thomas. Ambient Rhetoric: The Attunements of Rhetorical Being. U of Pittsburgh P, 2013.

Rivers, Nathaniel. “Deep Ambivalence and Wild Objects: Toward a Strange Environmental Rhetoric.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 45, no. 5, 2015, pp. 420-440.

Ruiz, Iris D., and Sonia C. Arellano. “La Cultura Nos Cura: Reclaiming Decolonial Epistemologies through Medicinal History and Quilting as Method.” Rhetorics Elsewhere and Otherwise: Contested Modernities, Decolonial Visions, edited by Romeo García and Damián Baca, NCTE, 2019.

Safran, Rebecca Jo. “Adaptive Site Selection Rules and Variation of group Size of Barn Swallows: Individual Decisions Predict Population Patterns.” The American Naturalist, vol. 164, no. 2, 2004, pp. 121-131.

Saino, Nicola, et al. “Climate Warming, Ecological Mismatch at Arrival and Population Decline in Migratory Birds.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B, vol. 278, no. 1707, 2011, pp. 835-842.

Saulmon, Greg. “Plan for Stables at Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge in Hadley Brings Protest, Legal Action — And Hope for Research on Saving Barn Swallows.” The Republican, 7 April 2019, www.masslive.com/news/2019/04/plan-for-stables-at-silvio-o-conte-national-fish-and-wildlife-refuge-in-hadley-brings-protest-legal-action-and-hope-for-....

“Search Engine: Highway Structure for the Birds.” Niagara Falls Review, 20 November 2015, http://www.niagarafallsreview.ca/news/niagara-region/2015/11/20/search-engine-highway-structure-for-the-birds.html.

Stormer, Nathan, and Bridie McGreavy. “Thinking Ecologically About Rhetoric’s Ontology: Capacity, Vulnerability, and Resilience.” Philosophy & Rhetoric, vol. 50, no. 1, 2017, pp. 1-25.

Sutton, Jane S., and Mari Lee Mifsud. “Towards an Alloiostrophic Rhetoric.” Advances in the History of Rhetoric, vol. 15, 2012, pp. 222-233.

TallBear, Kim. “Why Interspecies Thinking Needs Indigenous Standpoints.” Society for Cultural Anthropology, 18 November 2011, culanth.org/fieldsights/260-why-interspecies-thinking-needs-indigenous-standpoints.

Thomas, Chris D., et al. “Extinction Risk from Climate Change.” Nature, vol. 427, no. 6970, 2004, pp. 145-148.

Thrift, Nigel. Non-Representational Theory: Space, Politics, Affect. Routledge, 2008.

Todd, Zoe. “An Indigenous Feminist’s Take on the Ontological Turn: ‘Ontology’ is Just Another Word for Colonialism.” Journal of Historical Sociology, vol. 29, no. 1, March 2016, pp. 4-22.

Trewavas, Anthony. “Aspects of Plant Intelligence.” Annals of Botany, vol. 92, no.1, 2003, pp.1-20.

Tonino, Leath. “Two Ways of Knowing: Robin Wall Kimmerer on Scientific and Native American Views of the Natural World.” The Sun, April 2016. www.thesunmagazine.org/issues/484/two-ways-of-knowing,

Tsing, Anna. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton UP, 2015.

Turner, Angela. The Barn Swallow. T&A D Poyser, 2006.

Watts, Vanessa. “Indigenous Place-Thought and Agency amongst Humans and Non-Humans (First Woman and Sky Woman go on a European World Tour!).” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education, and Society, vol. 2, no. 1, 2013, pp. 20-34.

Webster, Richard. The Encyclopedia of Superstitions. Llewellyn, 2008.

Wilson, Shawn. Research is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. Fernwood Publishing, 2008.

Yusoff, Kathryn. A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None. U of Minnesota P, 2019.