Ruth Osorio, Old Dominion University[1]

(Published May 26, 2020)

In 2009, Autism Speaks, the largest autism-focused organization in the United States, released a public service announcement entitled “I Am Autism.” In the three-minute video, a deep, menacing voice introduces himself as Autism, the disorder itself, and speaks to non-autistic parents of autistic children. As ominous music plays in the background, Autism threatens parents and pledges to destroy their lives: “If you are happily married, I [Autism] will make sure that your marriage fails . . . I will plot to rob you of your children and your dreams . . . I will make sure every day you wake up, you will cry wondering, ‘Who will take care of my child when I die?’” (“I Am Autism”). In the final minute of the video, non-autistic parents take over as narrators, declaring their commitment to defeating Autism through a coalition of other parents, scientists, doctors, and educators. The video quickly drew controversy, with autistic adults denouncing the autism.[2] Ari Ne’eman, president of the Autistic Self-Advocacy Network (ASAN)—an autistic-led autistic advocacy group—criticized the video, explaining, “We don't want to be portrayed as burdens or objects of fear and pity” (Wallis). In response to overwhelming criticism by autistic people, Autism Speaks took down the video, apologizing for the harm caused while still justifying the validity of its message.

The video relied on a key topos related to autism: autism is bad. Fortunately, topoi are not static. As rhetorical scholars who have recently returned to the concept of topoi and expanded upon its function explain, topoi can help rhetors generate novel arguments, circulate within and across borders, and adapt to new sources of knowledge (Cintrón; McKeon; Miller; Olson). Autistic activists have taken to social media to generate, circulate, and impart their own novel topoi that counter the dominant beliefs of autism and create space for autistic activists and their allies to generate novel lines of argument. See, for instance, Twitter user @ThatGirlRea’s reclamation of the phrase, “I am Autism,” ten years after the video was published:

I’m aware the phrase ‘I am autism’ has been used to cast a negative shadow our way. I’m reclaiming this phrase. It does not belong to them. I used the phrase ‘I am autism, autism is me’ when I made my diagnosis public. This is me reclaiming those words. #ActuallyAutistic. (@ThatGirlRea)

@ThatGirlRea rejects the pathologizing topos of autism’s badness presented in the video, and instead uses the phrasing to introduce an alternate commonplace: maybe autism isn’t something to be shunned, but rather, an identity to publicly claim. The tweet ends with the hashtag #ActuallyAutistic, connecting @ThatGirlRea’s argument to an active movement of autistic activists who are reclaiming the conversation and introducing, revising, and circulating their own topoi related to autism.

This paper examines the clash between dominant topoi about autism and #ActuallyAutistic topoi on Twitter. While the Autism Speaks video illustrates the material and discursive violence of dominant topoi about autism, the #ActuallyAutistic writers demonstrate how autistic activists reclaim power through the articulation of affirming autist-topoi. No topos is factually objective, of course. Aristotle conceived of topoi as lines of arguments, generally accepted commonplaces rhetors can return to in order to develop arguments. As the video indicates, much argumentation about autism by non-autistic people returns to the commonplace of autism’s badness—and thus its need to be eliminated. The topos reveals its embodied impact; as autistic rhetorician M. Remi Yergeau illustrates, dominant topoi on autism motivate violence against autistic people from non-autistic family members, police, educators, and passersby, with the justification that autistic behaviors should be eradicated at all costs (Authoring).

Autistic activists have responded to such oppressive topoi by creating what I am calling autist-topoi—topoi constructed by autistic people that counter dominant, oppressive arguments about autism while offering places for autistic rhetors to return to and create new arguments. By combining autist and topoi in the term autist-topoi, I follow the lead of autistic scholar-activists Irene Rose and M. Remi Yergeau, who use the autist prefix to denote autistic genres written by autistic people for autistic people. Because autistic people are assumed to be incapable of telling their stories in any genre, the autistic adaption of existing genres to serve autistic needs subverts expectations of who can tell stories. Autist-texts, such as autist-ethnographies, operate intertextually and interrelationally to “narrate and protest oppression” (Yergeau, Authoring 24). Autist-topoi function similarly, as this study demonstrates: autist-topoi function as collaboratively written lines of argument that operate intertextually and interrelationally to narrate and protest oppression while authoring new futures for autistic people.

In this article, I demonstrate how the #ActuallyAutistic hashtag has become a storehouse of autist-topoi, a place for autistic people and their allies to locate, revise, and circulate liberatory arguments that support the dignity of autistic people. Recognizing that non-autistic people leveraged the autism tag of social media to promote topoi of erasure/violence, autistic activists created the #ActuallyAutistic hashtag in 2011 to claim an autistic space for and by actually autistic people (Hillary). Though the tag originated on the blogging site Tumblr, #ActuallyAutistic writers quickly transported it and its autist-topoi to Twitter by 2012, allowing for a wider audience and greater access to public figures discussing autism (@Marikunin). When Autism Speaks releases a video, fundraising campaign, or press release, the #ActuallyAutistic community is among the first to respond on Twitter, furthering the reach of its autist-topoi: autism is not the source of autistic people’s struggle, but rather, anti-autistic ableism is. #ActuallyAutistic tweeters also share stories of anti-autistic bias, celebrate rare positive portrayals of autistic people in popular culture, and circulate writing and art created by autistic people. What unites these seemingly disparate functions is a unifying argument: autism is a political, cultural, and personal identity.

The autist-topoi constructed by #ActuallyAutistic writers speaks back to many of the dominant topoi about autism: rather than isolated, noncommunicative, and unfeeling, #ActuallyAutistic tweeters are interconnected, persuasive, and emotionally charged. Dominant stereotypes about autism presume that autistic people can’t communicate their reality and advocate for themselves. However, rhetorical scholars Yergeau, Paul Heilker, and Jordynn Jack have argued that autistic people not only create rhetoric, but they do so on their own terms, framing autistic forms of expression as meaningful rather than pathological. I build upon their work by illustrating how autistic activists created, sustain, and leverage the hashtag #ActuallyAutistic to craft, revise, and circulate autist-topoi. I make two primary moves. First, I argue that #ActuallyAutistic pushes against material and discursive violence that emerges from dominant topoi about autism by collectively crafting, revising, and circulating autist-topoi that uplift the autistic community. Second, I offer to the field a study of how such a community leverages a hashtag as a storehouse of activist topoi, maintaining a digital space that responds to dominant topoi at the same time as it opens new possibilities for talking about and with autistic people. To make these claims, I begin with a brief overview of the dominant topoi about autism, and then I outline my methods and methodology. After, I turn to the data and present three autist-topoi most common to #ActuallyAutistic tweets: prioritizing experiential expertise, embracing neurodivergence, and documenting anti-autistic ableism.

Disabling Topoi

In this paper, I study the crafting of autist-topoi on Twitter, exploring how autistic activists create new topoi that advance the arguments, rights, and inherent value of autistic people. I approach autist-topoi similarly to how Christa J. Olson examines topoi of Ecuadorian nationalism: as “nodes of social value and common sense that provide places of return for convening arguments across changing circumstances” (6). Olson’s definition anchors topoi in community; topoi connect lines of argument that emerge from commonly shared understandings and values. What the #ActuallyAutistic topoi illustrate is how a community that is deemed to lack “common sense” creates arguments based on their own neurodivergent logic and values that resist the oppressive topoi imposed by a dominant, ableist community.

Looking at conversations among non-autistic doctors, educators, cognitive scientists, parents, and policy writers, we can see how dominant topoi about autism emerged from a collective distrust of mental disability and deviation from typical forms of expression. The most influential definition of autism comes from the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), the Holy Bible of psychologists and psychiatrists, which positions itself as an objective taxonomic and diagnostic tool for mental disorders. Although the DSM-5 has been robustly criticized by disability activists and scholars for its pathologizing and universalizing language, it remains the gateway for diagnosis, and thus, for receiving medical care and accommodations (Price 34-36). The DSM-5 describes autism as a series of deficits, such as difficulties with language, difficulties with emotional and social interactions, repetitive behaviors and movements, insistence on routines, and intense interest in “unusual objects.” Within the DSM-5’s lists of symptoms, the words “deficit” and “abnormal” are used, framing autism as a lack, a divergence. Thus, to dominant medical definitions, and to institutions like education that rely on medical definitions in order to provide accommodations, autism is a disorder that impairs the autistic person and prohibits them from “normal” forms of expression, communication, and persuasion.

The framing of autism as a rhetorical deficit informs how autism is portrayed in popular discourse, especially how philanthropic efforts echo pathologizing topoi about autism. One startling yet fairly accepted example is the “Locked in for Autism” fundraiser held by Caudwell Children, a non-profit organization that supports disabled children in the United Kingdom. For the event, non-autistic people collect donations and then lock themselves into a glass box for fifty hours. The box is meant to symbolize the autistic experience. The website explains:

Many [non-autistic] parents of autistic children have confirmed that the box is a metaphor for autism—the isolation, difficulties with communication and being stared at from all directions, with a sense of sometimes ‘feeling trapped,’ are often associated with the condition. (“Locked In”)[3]

According to such imagery, autistic people are removed physically and existentially from their potential audience, locked away from the world. Cognitive science writing similarly portrays the autistic person as incapable of understanding others’ viewpoints and thus incapable of communicating their own viewpoints to others. Simon Baron-Cohen, Alan M. Leslie, and Uta Frith’s influential paper, “Does the Autistic Child Have a Theory of the Mind,” argues that autistic children lack a theory of the mind (ToM), the knowledge that other people have their own thoughts, needs, feelings, and beliefs. Baron-Cohen, Leslie, and Frith assert that, because of the “inability to represent mental states . . . [autistic people] are unable to impute beliefs to others and are thus at a grave disadvantage when having to predict the behaviour of other people” (43). ToM, as Yergeau has repeatedly shown, casts autistic people as non-human and serves as justification for abusive training procedures designed to force autistic children to behave like neurotypical children. Dominant medical, philanthropic, and scientific arguments on autism, then, return to the same topos circulated by the “I Am Autism” video: autism is bad. Very often, the argument then follows: because autism is bad, it needs to eliminated, either by researching a cure, training autistic children to behave neurotypically, or removing autistic people from society through institutionalization or violence (Yergeau, Authoring and “Clinically”).

Yergeau, alongside other disability rhetoric scholars, has challenged such depictions of autistic people as non-rhetorical by claiming that autism is a form of rhetoric. In their article “Autism and Rhetoric,” Yergeau and Heilker argue that, despite scientific and rhetorical writings that suggest otherwise, autism is inherently rhetorical: “We contend that autism itself is a rhetoric, a way of being in the world through language, a rhetoric we may not have encountered or recognized frequently in the past nor value highly in academic contexts, but rhetoric nonetheless” (487). Heilker and Yergeau’s redefinition of autism as a rhetoric echoes the efforts of scholars such as Margaret Price, Jay T. Dolmage, Brenda Jo Brueggemann, and Catherine Prendergast to expand the boundaries of rhetoric to include disabled expression. Dolmage argues, “[D]isability shapes our available means of persuasion” (289). For disability rhetoric scholars, then, disabilities such as autism do not prevent rhetoric—they facilitate the invention and delivery of meaning. Indeed, autist-topoi on Twitter illustrate the rhetorical and political possibilities of autistic forms of expression.

On Activist Twitter: Theories and Methodologies

Scholars within the field of rhetoric and composition have largely embraced hashtag activism as powerful spaces where rhetors can circulate discourse about power, identity, and oppression (Dadas; Joyce; McCaughey; Penney and Dadas). Guobin Yang argues that hashtag activism is particularly suited for rhetors displaying narrative agency: “I consider narrative agency in hashtag activism as the capacity to create stories on social media by using hashtags in a way that is collective and recognized by the public” (14). Indeed, hashtags allow for rhetors—especially rhetors who have been denied a public platform—to collectively create, share, and build upon stories that are not represented in dominant culture. For autistic rhetors, Yergeau argues, storying holds great power, as they “resist the cultural inscriptions that autism as a diagnosis suggests” (Authoring Autism 24). In my study, autistic activists take full advantage of Twitter as a site to disabuse dominant topoi and revise them, reimagining autistic futures through their own autist-topoi.

As with feminist, anti-racist, and anti-capitalist hashtags, disability-focused hashtags offer a discursive space to craft subversive stories, organize activist interventions, and affirm marginalized identities. Furthermore, for many disabled and autistic protestors, hashtag activism is the most accessible form of protest. At a 2014 keynote at the Computers and Writing conference, Yergeau described how disability activism thrives on social media:

Disability culture is distributed; our network is largely virtual; we are often netroots activists because we lack f2f [face-to-face] options. While only twenty of us may have the means to physically protest exclusionary practices at an Autism Speaks walk, several hundred of us are able to participate in Twitter campaigns that target Autism Speaks’s corporate sponsors. (Yergeau, “Disable All the Things”)

Traditional street activism—marches, rallies, sit-ins—are often inaccessible to disabled people, autistic and otherwise; autistic people in particular may struggle with the high sensory output and the large group setting of a rally or march. Autistic activists have thus congregated on social media sites such as Twitter, leveraging their limitations and affordances for community building and organizing amongst autistic activists.[4]

Methods and Methodologies

Although I could find plenty of scholarship justifying hashtag activism as a source of study, I found less writing on how to approach tweets ethically. For this, I turned to cultural rhetorics, a field of study that pushes researchers to see themselves in relation to the communities they study (Powell et al.). In the collaboratively written article “Our Story Begins Here: Constellating Cultural Rhetorics,” Daisy Levy reminds us, “research is about people. It affects people. It can save and destroy lives” (Powell et al.) As a neurodivergent but non-autistic scholar, it was incredibly important for me to approach the activists who use this hashtag as people and not just data. I also was mindful of my position as an outsider of this community. Cultural rhetorics cautions scholars against replicating colonial methodologies, so rather than acting as a voyeur to the hashtag, I tried to approach the discourse as an eager student, learning the language, values, and politics of the community.

#ActuallyAutistic Twitter provided a rich space for me to practice cultural rhetorics in digital writing research. The hashtag is a nexus of autistic organizing online, and thus an ideal site to study how autist-topoi emerge through collective storying in digital spaces. The hashtag is incredibly active—I initially collected 56,346 public #ActuallyAutistic tweets over 16 months between 2015-2016. For the study, though, I wanted to focus my analysis on the hashtag’s most visible month, both in terms of volume and content: April 2016.[5] April is Autism Awareness Month, an effort coordinated by Autism Speaks that the #ActuallyAutistic community largely condemns because of Autism Speaks’s routine circulation of the “autism is bad” topos. In 2011, autistic people reclaimed April, renaming it Autism Acceptance Month. The shift from awareness to acceptance had a decidedly activist intent. As queer disabled writer Alaina Leary describes, Autism Acceptance Month is about “equal rights and justice for the autistic community, treating autistic people with autonomy and respect, and adopting a ‘nothing about us without us’ mindset that autistic people should be at the center of conversations about autism.” Because April features a proliferation of pathologizing topoi by dominant philanthropic organizations, autistic activists work doubly hard to drown those topoi with their own pointedly activist autist-topoi on Twitter.

After I narrowed my dataset to April 2016, I ended up with 1,961 unique public tweets. Thus, for this study, I immersed myself in my dataset for several months, reading, coding, and analyzing the tweets. By the time I concluded my open coding process, I had observed and coded twenty subcategories that could be grouped up into three topoi (Fig. 1). Following cultural rhetorics practices, I strove to represent the intentions of the community with my codes. For instance, I realized that the writers frequently engaged with the concept of expertise—the word “expert” appears eight times in the corpus—indicating that claiming autistic expertise was a central value of the #ActuallyAutistic community. Thus, I added identifying experts to my codebook.

|

Autist-topos 1: prioritizing experiential expertise |

|

|

criticizing Autism Speaks |

650 |

|

instructing non-autistic allies |

499 |

|

identifying autistic people as experts |

233 |

|

Autist-topos 2: embracing neurodivergence |

|

|

describing autistic life |

489 |

|

sharing autistic creative works |

425 |

|

offering/asking for support |

217 |

|

Autist-topos 3: documenting anti-autistic ableism |

|

|

naming and describing ableism |

462 |

|

criticizing the medical model of autism |

160 |

|

seeking accommodations |

53 |

Fig. 1. Chart of Codes Grouped by Autist-Topoi and Listed by Frequency.

I included the top three codes for each autist-topos. I’ve included a complete codebook in the appendix. For the autist-topos of prioritizing experiential expertise, the top three codes are: criticizing Autism Speaks (650), instructing non-autistic allies (499), and identifying autistic people as experts (233). For the autist-topos of embracing neurodivergence, the top three codes are: describing autistic life (489), sharing autistic creative works (425), and offering/asking for support. For the autist-topos of documenting anti-autistic ableism, the top three codes are: naming and describing ableism (462), criticizing the medical model of autism (160), and seeking accommodations (53).

Despite the short length of the tweets (at the time of the study, tweets were limited to 140 characters), many engaged in multiple categories. For example, on April 5, 2016, user @AnEndInItself tweeted:

There's no need to solve me, cure me, fix me or change me. It's much easier (and cheaper) to listen to me. #ActuallyAutistic #WAAW2016. (@AnEndInItself)

I recorded this tweet as having three codes: criticizing dominant discourse on autism, instructing allies on how to support autistic people, and criticizing the medical model of autism—the pathological model of autism presented by the DSM.

Re-reading the tweets as well as the codes, I realized that most of the codes served three distinct argumentative functions, which I refer to as autist-topoi: (1) prioritizing experiential expertise, (2) embracing neurodivergence, and (3) documenting anti-autistic ableism. I contacted most of the authors of the tweets I cite in this article in summer of 2019. Acknowledging the labor required of activist writing in digital spaces, I wanted to make sure I gave credit to the creators of the arguments I discuss in this article. Inspired again by cultural rhetorics methodologies, I introduced myself on Twitter as a non-autistic neurodivergent researcher, explained the project, and offered authors the opportunity to read the essay. The authors of the tweets included in this article gave consent for their inclusion, and I didn’t cite any individual tweets that had been deleted since 2016. A handful of tweets belong to accounts that have been de-activated; because I was not able to contact the authors of these tweets, I changed their usernames to maintain anonymity. I hope that these methods have enabled me to recognize the incredible labor of maintaining an activist hashtag while honoring the privacy of writers whose use of Twitter changed over time.

Revising, Rewriting and Reimaging Autism with Autist-Topoi

Heilker and Yergeau argue that “students on the autism spectrum, like all students, have their own culturally and individually distinctive topoi, tropes, dialects, and so on, and their rhetorics thus constitute both cultural and individual representations of their selfhood” (496). My research echoes their claim, adding that autistic activists collectively construct autist-topoi as a means of dismantling oppressive ideologies and enacting liberatory autistic futures. In this section, I analyze the three most prevalent autist-topoi in the #ActuallyAutistic hashtag—prioritizing experiential expertise, embracing neurodivergence, and documenting anti-autistic ableism—illustrating how each autist-topos builds upon the other to create space for autistic people to imagine a world without ableist violence.

Autist-Topos 1: Re-directing the Discussion by Claiming Expertise

The autist-topos of prioritizing the lived experiences of autistic people functions in direct opposition to the dominant discourse about autism expertise. As illustrated above, autistic people are not trusted to understand their own experiences, so non-autistic people are asked to define and explain autism. For autistic people to assert themselves as experts, they have to de-legitimatize two ableist topoi in dominant autism discourse: (1) that autistic people are locked in and removed from reality, and thus incapable of understanding and articulating their knowledge of autism; and (2) that, because of autistic people’s “deficits,” non-autistic parents, advocates, doctors, and cognitive scientists must speak on their behalf. The #ActuallyAutistic tweeters combat these two topoi by offering a new one, the autist-topos that argues expertise on autism is based on lived experience of autism.

Because Autism Speaks is so often heralded as the authoritative source on autism, #ActuallyAutistic users attack Autism Speaks’s authority while establishing their own. Out of 1,961 tweets, 650 feature a critique of Autism Speaks and other dominant discourses on autism. Of those 650 tweets, 73 tweets are coded as both criticizing Autism Speaks and identifying autistic people as experts. For instance, @TwitterUser1 tweeted on April 2, 2016:

Don't donate to autism Speaks, don't light up blue and speak with #ActuallyAutistic ppl to get the real facts. (@TwitterUser1)

On April 2, 2016, user @Falcc made a similar argument:

Never forget, Autism $peaks is a hate org that supports eugenics. Don't #LightItUpBlue [Autism Speaks’s international campaign] with this hate group. Listen to the #ActuallyAutistic. (@AFalcc, “Never forget”)

Within the limited character constraints of Twitter, @TwitterUser1 and @Falcc dismantle Autism Speaks’s claim to speak on behalf of autistic people and identify autistic people as experts. The activists direct non-autistic people not to Autism Speaks or the DSM, but to autistic people as the source of “real facts.”[6] @TwitterUser1, @Falcc, and hundreds of other #ActuallyAutistic tweeters are redefining expertise based on experience and embodied knowledge. In other words, whereas doctors, teachers, and researchers may claim expertise on autism based on outside research and credentials, #ActuallyAutistic tweeters claim expertise on autism based on their lived experiences of autism. This autist-topos redefines authority to be based on lived experience of autism; in other words, while non-autistic “experts” argue that autistic people cannot be trusted because of their autism, autistic activists argue that the very fact of their autism increases their credibility in conversations about autism. By doing so, autistic activists validate autistic commonsense as trustworthy, thus creating space for the authoring of more autist-topoi within and beyond the community.

In order to position themselves as authorities, autistic activists apply sitpoint theory to discredit the dominant pathologizing topoi that circulate widely. Rosemarie Garland-Thomson describes sitpoint theory as a disabled epistemology, the kind of knowledge that emerges from moving through the world as a disabled person and, thus, should be considered authoritative (21). User @cheetahpeople simultaneously elevates herself as an expert because of her lived experiences of autism as she disregards dominant perspectives and topoi of autism:

hi im #actuallyautistic and i can tell you most of the facts on ur school's autism poster [sic] are either bullshit or unhelpful. (@cheetahpeople)

In this tweet, @cheetahpeople crafted an enthymematic argument with a critical yet unstated premise: that @cheetahpeople’s lived experience as an autistic person outweighs the knowledge presented in posters in terms of credibility, posters presumably created by non-autistic autism “experts.” By merely implying the premise—that lived experience trumps book learning—@cheetahpeople operates as if this premise is universally accepted. Indeed, the unstated premise is often what makes enthymemes so effective. By inviting the audience to construct the argument on their own, @cheetahpeople evokes sitpoint theory to reframe commonsense assumptions that typically silence autistic people to amplify their stories instead—of course life experience leads to expertise, and therefore, autistic people are experts of life with autism. Dolmage explains sitpoint theory’s applicability to rhetorical studies: “Sitpoint theory would show that knowledge creation is always rhetorical—a flow of power through bodies—and thus disability is both usefully and ‘naturally’ at the center of a process of knowing” (129). By leveraging sitpoint theory, autistic activists underscore that their ethos is grounded in their experiences of disability, a source of knowledge that elevates their authority above those whose knowledge comes from textbooks or studies authored by non-autistic people.

In many of these tweets, the hashtag itself functions as an autist-topos. As @Falcc’s and @TwitterUser1’s tweets illustrate, many of the #ActuallyAutistic community members use the hashtag as an identifier within their tweet. On April 20, 2016, @chromesthesia tweeted:

It's just not accurate to rely solely on autism narratives by parents and “experts”. #actuallyautistic people live it and understand better. (@chromesthesia)

@chromesthesia echoes the 230 tweets directly identifying autistic people as experts, specifically naming lived experience as the source of their superior knowledge. The hashtag thus operates as an autist-topos, as #ActuallyAutistic people are identified as distinct from non-autistic people, as capable of producing rhetoric about autism, and as more credible than non-autistic people on the topic of autism. The grammatical phenomenon of incorporating the hashtag into the syntax of the tweet occurs 1,403 times in the corpus—far and away the most commonly reoccurring code.

Whereas the hashtag itself operates as an autist-topos that is declaring autistic expertise, #ActuallyAutistic tweeters speak directly to non-autistic people who (perhaps unwittingly) promote oppressive topoi about autism. In April 2016, 241 #ActuallyAutistic tweets directly appealed to public figures and corporations that promoted Autism Speaks. These appeals attempted to re-direct attention to autistic activists, highlighting the harm of Autism Speaks and the dominant topoi on autism, as well as the values and concerns of autistic people. After journalist Katie Couric tweeted in support of the Light It Up Blue campaign, @IndubitablyISFP replied directly to both Couric and Autism Speaks on April 3, 2016:

@katiecouric @autismspeaks If you want to support #ActuallyAutistic people, please listen to us & do #RedInstead! Not #LIUB - that hurts us. (@IndubitablyISFP)

Here, @IndubitablyISFP connects their tweet to the autistic-led Walk in Red campaign with the tag #REDInstead. Rather than “lighting it up blue,” or LIUB, as Autism Speaks invites, #ActuallyAutistic activists wear red on April 2 to celebrate their autistic identities (#WalkInRed). In these cases, #ActuallyAutistic people present their autist-topos of experiential expertise to the non-autistic world, inviting the readers to question their own assumptions about expertise, authority, and autism. #ActuallyAutistic activists knowingly enter conversations centered around ableist topoi in order to reclaim the conversation and introduce autist-topoi that open new arguments and stories about autistic people.

In addition to tweeting directly at public figures, #ActuallyAutistic writers also address non-autistic people generally by instructing them on how to be better allies. Non-autistic people, then, are provided with the tools to circulate autist-topoi amongst their community, furthering the reach of liberatory autist-topoi on Twitter and beyond. In these tweets, #ActuallyAutistic writers again supplant non-autistic parents, Autism Speaks, and autism researchers as the experts, and direct non-autistic advocates and supporters to autistic-led organizations and to autistic people as the authoritative sources on autism. In the 499 tweets coded as “instructing allies,” #ActuallyAutistic tweeters act as teachers, instructing non-autistic people on how to support autistic people. On April 2, 2016, @TwitterUser2 tweeted:

If you truly care and support autistic people take your time to listen to #ActuallyAutistic people instead of a hate group that silences us. (@TwitterUser2)

Similarly, on April 2, 2016, @C_Squared2911 tweeted:

For #WorldAutismAwarenessDay, PLEASE listen to those of us who are #actuallyautistic. Our voices- whether in speech or otherwise- matter. (@C_Squared2911)

In both tweets, the writers guide non-autistic people on how to support and care for autistic people: to listen. In fact, out of the 499 tweets coded as instructing allies, the word “listen” appears 69 times. As Krista Ratcliffe argues in Rhetorical Listening: Identification, Gender, and Whiteness, listening is a decidedly rhetorical and activist act that especially enables cross-cultural conversation and understandings, including cultural communities like the autism community (25). Thus, the #ActuallyAutistic activists leverage their authority and expertise to instruct non-autistic people on how to communicate with autistic people.

As non-autistic people increasingly consult autistic people as experts, non-autistic people can absorb and circulate autist-topoi, extending the reach of autist-topoi into conversations about autism in policy, philanthropy, and education. Indeed, #ActuallyAutistic writers have persuaded businesses such as Panera and ThinkGeek to redirect their philanthropy away from Autism Speaks and toward autistic-led advocacy groups, with ThinkGeek vowing to listen to autistic people when planning autism charity because #ActuallyAutistic people “are the experts on this” (Gouldin, emphasis in original). As non-autistic people turn to autistic people for instruction, non-autistic allies are positioned to learn and circulate additional autist-topoi in their circles, widening the reach of empowered, affirming, and political autist-topoi anchored in neurodiversity and disability justice.

Autist-Topos 2: Redefining Autism as Neurodivergent Expression

With #ActuallyAutistic tweeters positioned as the experts in conversations about autism, they have the platform to eradicate the big bad topos that drives so much of the argumentation surrounding autism: autism’s badness. The #ActuallyAutistic community takes down this violent definitional topos by replacing it with their own autist-topos: autism is just another way of moving through the world, an example of the neurodiversity that makes up human experience. Tweets that prioritize experiential experience are generally directed toward non-autistic people, but much of the activist work in the #ActuallyAutistic tag is directed toward fellow autistic people. And yet, although these conversations are geared toward each other, they are ultimately public facing in that non-autistic users of Twitter can also observe the conversations. In this discussion that straddles the line between public and private, #ActuallyAutistic people offer new definitions of autism, definitions that situate autism not as a deficit but as a neurodivergent way of being, moving, and thinking. This autist-topos centers on the concept of neurodiversity: the idea that humans have different neurologies and that these differences should be celebrated rather than quelled (Harmon; Jack). Hundreds of tweets engage with this autist-topos, with 489 tweets describing autistic life, 169 tweets expressing autistic pride, and several other distinct rhetorical moves that work to redefine autism. However, I focus this section on a close reading of one tweet that exemplifies this autist-topos by reframing autistic modes of expression as natural, autistic ways of communicating.

Throughout the redefining autism autist-topos, the #ActuallyAutistic community redefines behaviors associated with autism as central to autistic life and culture, rather than symptoms of pathology. As Aristotle writes in Topics, definitional topoi are crucial to argumentation. Indeed, #ActuallyAutistic tweeters are well aware of the impact of the various definitions of autism—their lives have been shaped by definitions that frame autistic characteristics as problems to be solved. For example, the DSM-5 lists “stereotyped or repetitive motor movements, use of objects, or speech” as one of the diagnostic criteria for autism, further explaining that severity can be determined by “social communication impairments and restricted repetitive patterns of behavior.” Thus, repetitive movement, called stimming or flapping, is described as pathological, as a hurdle to communication.

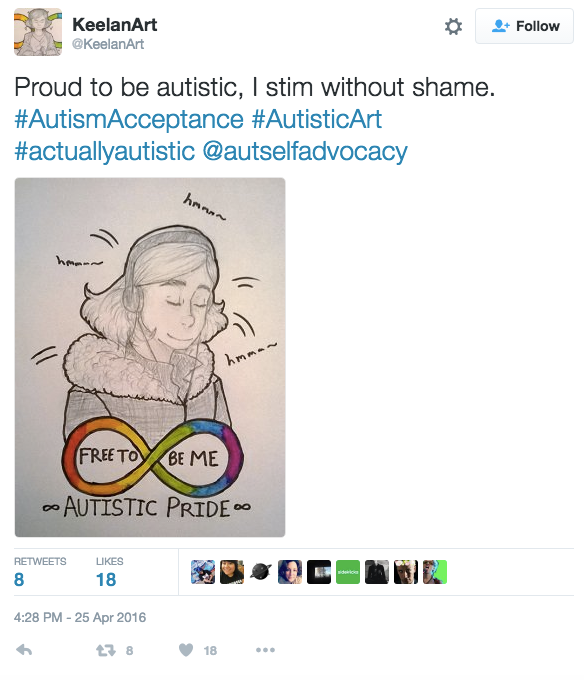

Because the topos of autism’s badness demands autism’s eradication, much of the education of autistic children seeks to purge the children of autistic expression. Indeed, stimming is so often pathologized, with non-autistic parents and educators incorporating Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) therapy to teach autistic children to move and act neurotypically. However, within the autist-topos of redefining autism, stimming is instead framed as a neurodivergent, and completely valid, mode of communication. On April 25, 2016, @KeelanArt tweeted (Fig. 2):

Proud to be autistic, I stim without shame. #AutismAcceptance #AutisticArt #actuallyautistic @autselfadvocacy. (@KeelanArt)

Fig. 2. “Free to Be Me” Tweet. The tweet is accompanied by an illustration of a person with closed eyes wearing headphones. Lines drawn around the person suggest stimming. Underneath the person, there is a rainbow infinity symbol with the handwritten text “Free to Be Me Autistic Pride.” Used with permission.

The tweet provides a multimodal embrace of stimming: @KeelanArt feels no shame about moving in a neurodivergent way and, indeed, feels pride about this aspect of their personality. To celebrate stimming, then, is to challenge medical discourse that portrays stimming as a deficit, as a sign of dysfunction.[7] By demonstrating autistic pride, and specifically pride in the act of stimming, @KeelanArt’s tweet redefines autism not as a disease but as a core element of their identity.

@KeelanArt and many other #ActuallyAutistic activists reclaim stimming not as a sign of deviance but as a form of expression and communication—in other words, a rhetorical act imbued with meaning. Yergeau similarly reclaims stimming in their book chapter, “Occupying Autism: Rhetoric, Involuntarity, and the Meaning of Autistic Lives.” In this chapter, Yergeau writes, “Hands move, air moves, sound waves, flitting fingers, motion before eyes. Here there is meaning. Stims tell a story” (93). Indeed, much of the tweets coded as “Autistic Life” celebrate stimming and flapping as meaningful gestures; of the 25 tweets that reference stimming, all frame stimming positively. By expanding the definition of rhetoric and communication to include neurodivergent forms of expression like stimming and flapping, #ActuallyAutistic writers redefine autism itself as variation of human neurology. According to the redefining work of this autist-topos, autistic people and their movements are valid and valued. Despite the positive reframing of autism, #ActuallyAutistic tweeters are the first to acknowledge that the experiences of autistic people are not universally positive. Importantly, the liberatory definitional work of #ActuallyAutistic tweeters underscores that autism itself is not bad and, thus, is not the cause of the difficulties they may face in their lives. Through the re-defining autist-topos, #ActuallyAutistic activists are able to direct attention to the actual source of barriers in their lives: anti-autistic ableism.

Autist-Topos 3: Activating Activism by Witnessing Anti-Autistic Ableism

The writers of #ActuallyAutistic redefine autism according to their own experiences, valuing neurodiversity over pathology in their expressions of autistic life and identity. The stakes are high for this work, as many of the tweets describe the discrimination and abuse autistic people face: 462 #ActuallyAutistic tweets in April 2016 documented experiences with and trends of anti-autistic ableism. The autist-topos of naming anti-autistic ableism highlights the exigence of the hashtag, providing harsh reminders that though the #ActuallyAutistic community has redefined autism for itself and its allies, many non-autistic people continue to belittle, abuse, and discriminate against autistic people. As @TwitterUser3 wrote on April 26, 2016:

We are disabled not by our cognitive differences, but by an ignorant and inflexible society #autism #actuallyautistic. (@TwitterUser3, “We are disabled”)

In this tweet, @TwitterUser3 diagnoses society as ignorant and rigid, noting that it, too, often refuses to accommodate the cognitive differences of autistic people. The autist-topos of naming the abuse of autistic people transforms conversations about the struggles of autistic people into political ones. By highlighting the systemic oppression of autistic people that stems from dominant topoi of autism, #ActuallyAutistic writers demonstrate the need for a systematic upheaval of ableist attitudes, policies, and discrimination. As Simi Linton writes, the very term ableism “can be used to organize ideas about the centering and domination of the nondisabled experience and point of view” (9). Thus, the autist-topos of witnessing anti-autistic ableism enables autistic people to articulate their experiences with anti-autistic ableism and then organize to counter it.

The autist-topos of witnessing ableism creates space for #ActuallyAutistic people to articulate the many different ways autistic people experience ableism. Within my dataset, 36 tweets also included the hashtag #AbleismExists, connecting autistic activists with the larger disability activism community on Twitter. Of the 36 #ActuallyAutistic tweets tagged with #AbleismExists, 19 are authored by @jrtgirl35. On April 24, 2016, @jrtgirl35 described ableism in the workplace:

#AbleismExists when I have to decide between wanting to keep my job and asking for the accommodations I need #ActuallyAutistic. (@jrtgirl35, “#AbleismExists when I have to”)

Again on April 24, 2016, @jrtgirl35 described ableism in the doctor’s office:

#AbleismExists when I go to a new doctor an they ask so your over this whole autism thing right like its a common cold #actuallyautistic. (@jrtgirl35, “#AbleismExists when I go to”)

On the same day, @jrtgirl35 also described ableism within their family:

#AbleismExists when people in my own extended family bully me and treat me badly just because I'm autistic #actuallyautistic. (@jrtgirl35, “#AbleismExists when people”)

On April 30, 2016, @jrtgirl35 described ableism in schools:

#AbleismExists when I can be bullied so badly I fear going into school because I'm autistic an no one stops it #actuallyautistic. (@jrtgirl35, “#AbleismExists when I can be”)

I quote four of @jrtgirl35’s #AbleismExists tweets to present the breadth of their tweets and stories of ableism. Even within the tight length constraints of Twitter—140 characters at the time—@jrtgirl35 provides brief but copious snippets of their experiences of bullying, dismissal, and stigma.

@jrtgirl35 leverages copia to create a public storehouse of examples of the witnessing-ableism autist-topos in action. As Jack’s work on autistic gender expression explains, autistic activists utilize copia—a rhetorical strategy involving strategic abundance, both in style and content, as a method for building persuasive arguments— to invent various ways of understanding autistic identities (201). Within #ActuallyAutistic Twitter, @jrtgirl35 uses copious illustrative examples of ableist expression to “convince one’s audience” of the presence of anti-autistic ableism (Erasmus 616). @jrtgirl deploys copia in their 19 tweets documenting various experiences of ableism, both revealing the abundance of ableism and the variety of its manifestations. The affordances of Twitter enable @jrtgirl35 to put forth many succinct examples of the autist-topos of witnessing ableism. Disabled activists argue that progressive activists often deny that ableism exists;[8] however, @jrtgirl35’s abundant examples provide exhaustive evidence that a single autistic person encounters ableism in multiple spheres of life. Thus, by deploying copia, @jrtgirl35 makes it difficult for nondisabled people to dismiss ableism. Furthermore, by producing an abundance of examples of ableism, @jrtgirl35 uses the autist-topos of witnessing ableism to move the audience to potentially organize against ableist ideologies that make work, the doctor’s office, family gatherings, and school into dangerous places for autistic people.

By bearing witness to #ActuallyAutistic tweeters’ own and each other’s experiences of ableism, this autist-topos serves a crucial activist function: affirming their experiences in a society that largely ignores ableism as a source of oppression. Multiple tweets of @jrtgirl35’s, in addition to being retweeted and liked, sparked conversation among other autistic people who had similar experiences. On April 25, 2016, @jrtgirl35 tweeted:

When #AbleismExists it’s ok for the largest and most well known autism organization to call autistic people empty shells #ActuallyAutistic. (@jrtgirl35, “When #AbleismExists it’s ok”)

@TwitterUser3 affirmed @jrtgirl35’s observations. The two tweeters exchanged their stories of being described as empty, with @TwitterUser3 concluding:

btw this is heartbreaking as hell. when i was diagnosed at age of 5, my diagnosis papers said “the kid has empty eyes.” (@TwitterUser3, “btw this is”)

Here, autistic people witness each other’s suffering, affirming that such treatment is indeed harmful. This justification is powerful. In this way, the witnessing ableism autist-topos echoes the activist and rhetorical work of women’s consciousness-raising groups in the 1970s. Karlyn Kohrs Campbell claims that these groups moved toward structural changes by articulating affective, personal accounts of marginalization (134). However, the women’s consciousness groups were by nature small, intimate groups. #ActuallyAutistic people, on the other hand, don’t necessarily live close to each other. Some do not meet another autistic person until adulthood. Therefore, the witnessing ableism autist-topos facilitates these affective, personal revelations in settings both large (as the tweets are public) and intimate (the discussions, though public, are often between two or three people sharing personal accounts of discrimination), conversations that validate autistic people’s experiences and move the community toward activist interventions.

A Place for Autistic Futures

The autist-topoi of #ActuallyAutistic writers underscore the material stakes of topoi. For autistic people, and indeed for all marginalized peoples, oppressive topoi can create real, material harm. @jrtgirl35’s tweets illustrate how ableist arguments about autism impede them in every sector of their life. @KeelanArt’s celebrations of stimming subvert dominant arguments about the need to eliminate autistic expression from children through abusive ABA practices. As other #ActuallyAutistic tweeters document, autistic people have been physically harmed and even murdered because of the unquestioned assumption of autism’s badness. Perhaps, then, it’s fitting that Aristotle conceived of topoi as places for people to locate arguments. His metaphor highlights the materiality of topoi, and the #ActuallyAutistic community extends our understanding of topoi by stressing the physical, emotional, and mental violence that oppressive topoi can inflict on marginalized people.

At the same time, autist-topoi provide hope: when autistic people reclaim the conversation, they drown out oppressive topoi with their own affirming autist-topoi that frame autism as a cultural, political, and rhetorical identity. Just as ableist topoi can oppress, autist-topoi can liberate, dismantling the discursive and material violence of anti-autistic ableism. #ActuallyAutistic tweeters imagine a world in which autistic people can stim openly without shame or violence, can live in communities instead of institutions, and can thrive in schools and workplaces. @Falcc invites non-autistic people to join in re-making the world to be embracing of autistic people, instructing non-autistic people to “be in community with #ActuallyAutistic people in your activism. We're not a charity for you to pity, we need a society that’s survivable” (@Falcc, “be in”). The imaginative and generative work of making a society survivable invokes autistic futures, what Yergeau describes as “autistic people’s cunning expertise in rhetorical landscapes that would otherwise render us inhuman” (Authoring Autism 5). Through their circulation of autist-topoi, autistic activists rewrite dominant topoi and, thus, discard the ableist topoi that undergird the violence autistic people encounter. Autist-topoi provide a place for autistic people to locate collectively crafted arguments, where neurodivergent sense is the common sense that unites the community and its discourse.

The autist-topoi I have analyzed here correspond with the rhetorical work that often occurs in offline activist movements: positioning marginalized people as experts, affirming the value of marginalized identities and cultures, and naming oppression. Writing Studies scholars Caroline Dadas, Joel Penney, and Chanon Adsanatham have similarly observed the parallels between offline and online activism in their studies of Twitter use in Occupy Wall Street and pro-democracy protests in Thailand, respectively. What I hope this study offers to the conversation is how a born-digital activist movement leverages the hashtag as a storehouse for liberatory topoi, a digital place for autistic people to contribute to the creation and sustainment of autist-topoi, and for non-autistic people to visit, listen, and then transport autist-topoi into their communities. Just as scholars such as Safiya U. Noble claim that algorithms inflict real, material harm on marginalized people, marginalized people can and have taken advantage of algorithms to circulate topoi that improve the material conditions of their communities (Noble). Activist hashtags, just like the topoi Aristotle described, are spaces that blend the discursive and the material, cataloging liberatory topoi written by the people often silenced in public spaces. The #ActuallyAutistic hashtag, then, exists as a place to return as activists imagine, utter, and then enact autistic futures that embrace the diverse ways humans move throughout the world.

Appendix

Here is my full, final code book, sorted by autist-topos and frequency of occurrence.

|

Autist-topos 1: prioritizing experiential expertise |

|

|

criticizing Autism Speaks |

650 |

|

instructing non-autistic allies |

499 |

|

appealing directly to strangers |

241 |

|

identifying autistic people as experts |

233 |

|

addressing non-experts |

135 |

|

interrogating functioning labels |

80 |

|

planning and promoting offline advocacy |

68 |

|

|

|

|

Autist-topos 2: embracing neurodviersity |

|

|

describing autistic life |

489 |

|

sharing autistic creative works |

425 |

|

offering/asking for support |

217 |

|

expressing pride |

169 |

|

analyzing autism in pop culture |

70 |

|

expressing gratitude |

59 |

|

acknowledging diversity |

52 |

|

reclaiming communication |

39 |

|

recognizing cross-disability solidarity |

16 |

|

|

|

|

Autist-topos 3: documenting ableism |

|

|

naming and describing ableism |

462 |

|

criticizing the medical model of autism |

160 |

|

seeking accommodations |

53 |

[1] Throughout the revision process, I was able to sharpen and strengthen this essay thanks to Laurie Gries and the reviewers’ insightful, engaged, and constructive feedback. They challenged me in exciting, generative ways, and I am forever grateful. I thank early readers of this work, Jessica Enoch, Chanon Adsanatham, Stephanie Kerschbaum, and Scott Wible. Shout out to my writing group, Elizabeth Ellis Miller, and Anne-Marie Womack for getting me to the finish line. My deepest gratitude to the rad autistic activists I spoke with throughout this study: thank you for changing the paradigm and making more space for neurodivergent folks online and off.

[2] Prominent autistic activists and organizations, such as Lydia Brown, Amy Sequenzia, and the Autistic Self-Advocacy Network, claim autism as an essential and positive aspect of their identity, and thus use identity-first language—“autistic person.” Furthermore, the writers on the #ActuallyAutistic tag use identity-first language, so I honor their preference and expertise by using identity-first language in this article.

[3] I found this language on the Caudwell Children website in 2016, when I began conducting this research. In 2017, Caudwell suspended Locked in for Autism fundraiser events after autistic activists pushed back (Not Locked In), and the language on the webpage has since been taken down. However, similar language still appears online to describe the event ("Locked in for Autism: Caudwell Children").

[4] Importantly, too, like all forms of activism, activism on Twitter is not a utopia. Twitter has made strides in developing accessibility features but still sets up obstacles for people who access the site via a screenreader (Christopherson; Ellis and Kent). And as Caroline Dadas demonstrates, digital “consciousness-raising does carry considerable consequences,” such as harassment, doxing, and threats (30). And yet, despite the risks, the writers of #ActuallyAutistic Twitter continue to contribute to the hashtag and challenge dominant tropes about the rhetorical power of autistic activists.

[5] March 2016 featured 1,047 unique tweets; at 1,961 unique tweets, April 2016 nearly doubled that number.

[6] In addition, the hashtag #BoycottAutismSpeaks occurs 102 times and is the tenth most used phrase in the corpus.

[7] @KeelanArt echoes Jason Nolan and Melanie McBride’s reframing of stimming as semiosis in their chapter, “Embodied Semiosis: Autistic ‘Stimming’ as Sensory Practice.”

[8] Dominick Evans, a disabled (non-autistic) filmmaker and activist, started the #AbleismExists hashtag on April 16, 2016, because many activists he encountered denied the prevalence of ableism. The hashtag quickly picked up steam, with other disabled people on Twitter joining in and sharing stories of their experiences with ableism. Evans explains, “I thought that perhaps if enough disabled people were sharing their experiences with ableism, then maybe people would begin to see how absolutely terrible we are treated by a world that often sees us as invisible” (Evans qtd. in Wanshel).

Adsanatham, Chanon. “Building a Digital Counterpublic: Civic Affordances of Twitter under Thai Authoritarian Government.” Social Media in Asia: Changing Paradigms of Communication, edited by Azman Azwan Azmawati and Rachel E. Khan, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016, pp. 130-153.

@AnEndInItself (JD). “There’s no need to solve me, cure me, fix me or change me. It’s much easier (and cheaper) to listen to me. #ActuallyAutistic #WAAW2016.” Twitter, 5 Apr. 2016, 4:57 p.m., twitter.com/AnEndInItself/statuses/717380636667940870.

Aristotle. “Topics.” The Complete Works of Aristotle: The Revised Oxford Translation, edited by Jonathan Barnes, Princeton UP, 1984, pp. 167-277.

Baron-Cohen, Simon, Alan M. Leslie, and Uta Frith. “Does the Autistic Child Have a ‘Theory of Mind’?” Cognition, vol. 21, no. 1, 1985, pp. 37–46.

Brown, Lydia. “The Significance of Semantics: Person-First Language: Why It Matters.” Autistic Hoya, 4 Aug. 2011, www.autistichoya.com/2011/08/significance-of-semantics-person-first.html.

Brueggemann, Brenda Jo. Lend Me Your Ear: Rhetorical Constructions of Deafness. Gallaudet UP, 1999.

@C_Squared2911 (Courtney Johnson). “For #WorldAutismAwarenessDay, PLEASE listen to those of us who are #actuallyautistic. Our voices- whether in speech or otherwise- matter.” Twitter, 2 Apr. 2016, 5:13 p.m., twitter.com/C_Squared2911/statuses/716297387816394753.

Campbell, Karlyn Kohrs. “The Rhetoric of Women's Liberation: An Oxymoron.” Communication Studies, vol. 50, no. 2, 1999, pp. 125–137.

@cheetahpeople (ace mcgayne). “hi im #actuallyautistic and i can tell you most of the facts on ur school's autism poster [sic] are either bullshit or unhelpful.” Twitter, 6 Apr. 2016, 6:18 p.m., twitter.com/cheetahpeople/statuses/717763391490801664.

Christopherson, Robin. “A Brief History of Accessibility on Twitter in Ten Tweets to Mark Twitter’s 10th Birthday.” AbilityNet, 21 Mar. 2016, www.abilitynet.org.uk/blog/brief-history-accessibility-twitter-ten-tweets-mark-twitters-10th-birthday.

@chromesthesia (Spider Doof Warrior). “It’s just not accurate to rely solely on autism narratives by parents and ‘experts’. #actuallyautistic people live it and understand better.” Twitter, 20 Apr. 2016, 5:31 p.m., twitter.com/chromesthesia/statuses/722825111019991040.

Cintrón, Ralph. “Democracy and Its Limitations.” The Public Work of Rhetoric: Citizen-Scholars and Civic Engagement, edited by John Ackerman and David J. Coogan, U of South Carolina P, 2010, pp. 98-116.

Dadas, Caroline. “Hashtag Activism: The Promise and Risk of ‘Attention.’” Social Writing/Social Media: Publics, Presentations, and Pedagogy, edited by Douglas M. Walls and Stephanie Vie, WAC Clearinghouse, 2017.

Dolmage, Jay T. Disability Rhetoric. Syracuse UP, 2014.

“DSM-5 Autism Diagnostic Criteria.” Autism Speaks, 29 July 2013, www.autismspeaks.org/what-autism/diagnosis/dsm-5-diagnostic-criteria.

Ellis, Katie, and Mike Kent. Disability and New Media. Routledge, 2011.

Erasmus, Desiderius. “Copia: Foundations of the Abundant Style.” The Rhetorical Tradition: Readings from Classical Times to the Present, 2nd ed., edited by Patricia Bizzell and Bruce Herzberg, Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2001, pp. 359-428.

@Falcc. “Be in community with #ActuallyAutistic people in your activism. We’re not a charity for you to pity, we need a society that’s survivable.” Twitter, 2 Apr. 2016 7:38 a.m., .

---. “Never forget, Autism $peaks is a hate org that supports eugenics. Don't #LightItUpBlue [Autism Speaks’ international campaign] with this hate group. Listen to the #ActuallyAutistic.” Twitter, 2 Apr. 2016, 3:31 p.m., .

Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie. “Integrating Disability, Transforming Feminist Theory.” NWSA Journal, vol. 14, no. 3, 2002, pp. 1-32.

Gouldin, Carrie. “Blurgh! The ThinkGeek Blog - April Charity Revealed; Help Us Choose May!” ThinkGeek, 8 April 2011, thinkgeek.com/blog/2011/04/april-charity-revealed-help-us.html.

Harmon, Amy. “Neurodiversity Forever: The Disability Movement Turns to Brains.” The New York Times, 9 May 2004, www.nytimes.com/2004/05/09/weekinreview/neurodiversity-forever-the-disability-movement-turns-to-brains.html.

Heilker, Paul, and M. Remi Yergeau. “Autism and Rhetoric.” College English, vol. 73, no. 5, 2011, pp. 485–497.

Hillary, Alyssa. “Yes, That Too: Why Actually Autistic Tag.” Yes, That Too, 2 Sept. 2014, www.yesthattoo.blogspot.com/2014/09/why-actually-autistic-tag.html.

“I Am Autism Commercial by Autism Speaks.” YouTube, uploaded by Find Yaser, 20 Apr. 2016, www.youtube.com/watch?v=9UgLnWJFGHQ

@IndubitablyISFP (Shannon DeYong). “@katiecouric @autismspeaks If you want to support #ActuallyAutistic people, please listen to us & do #RedInstead! Not #LIUB - that hurts us.” Twitter, 3 Apr. 2016, 5:57 a.m., twitter.com/IndubitablyISFP/statuses/716489695350226944.

Jack, Jordynn. Autism and Gender: From Refrigerator Mothers to Computer Geeks. U of Illinois P, 2014.

Joyce, Mary, editor. Digital Activism Decoded: The New Mechanics of Change. IDEBATE Press, 2010.

@jrtgirl35 (Lauren Norman). “#AbleismExists when I can be bullied so badly I fear going into school because I'm autistic an no one stops it #actuallyautistic.” Twitter, 24 Apr. 2016, 10:42 p.m., twitter.com/jrtgirl35/statuses/724352920314109955.

---. “#AbleismExists when I go to a new doctor an they ask so your over this whole autism thing right like its a common cold #actuallyautistic.” Twitter, 24 Apr. 2016, 10:30 p.m., twitter.com/jrtgirl35/statuses/724349735029641216.

---. “#AbleismExists when I have to decide between wanting to keep my job and asking for the accommodations I need #ActuallyAutistic.” Twitter, 24 Apr. 2016, 10:32 p.m., twitter.com/jrtgirl35/statuses/724350377018155008.

---. “#AbleismExists when people in my own extended family bully me and treat me badly just because I'm autistic #actuallyautistic.” Twitter, 24 Apr. 2016, 10:44 p.m., twitter.com/jrtgirl35/statuses/724353273285754881.

---. “When #AbleismExists it's ok for the largest and most well known autism organization to call autistic people empty shells #ActuallyAutistic.” Twitter, 25 Apr. 2016, 9:55 a.m., twitter.com/jrtgirl35/statuses/724642948592328704.

@KeelanArt. “Proud to be autistic, I stim without shame. #AutismAcceptance #AutisticArt #actuallyautistic @autselfadvocacy.” Twitter, 25 Apr. 2016, 12:28 a.m., twitter.com/KeelanArt/statuses/724741983290441728.

Leary, Alaina. “Autistic People are Taking Back Autism ‘Awareness.’ It’s About Acceptance.” Rooted in Rights, 17 Apr. 2018, www.rootedinrights.org/autistic-people-are-taking-back-autism-awareness-its-about-acceptance/.

Linton, Simi. Claiming Disability: Knowledge and Identity. New York UP, 1998.

“Locked in for Autism.” Caudwell Children, www.caudwellchildren.com/galleries/locked-in-for-autism/. Accessed 2016.

“Locked in for Autism: Caudwell Children.” Third Sector Awards, https://www.thirdsectorexcellenceawards.com/finalists/locked-in-for-autism/. Accessed 20 Apr 2020.

@Marikunin (Mary). “Off to another sensory overloaded day at work. #actuallyautistic #work.” Twitter, 9 Feb. 2012, 2:05 a.m., twitter.com/Marikunin/status/167549727406161921.

McCaughey, Martha, editor. Cyberactivism on the Participatory Web. Routledge, 2014.

McKeon, Richard. “Creativity and the Commonplace.” Philosophy & Rhetoric, vol. 6, no. 4, 1973, pp. 199–210.

Miller, Carolyn R. “The Aristotelian Topos: Hunting for Novelty.” Rereading Aristotle’s Rhetoric, edited by Alan G. Gross and Arthur E. Walzer, Southern Illinois UP, 2000, pp. 130-146.

Noble, Safiya U.. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. NY UP, 2018.

Nolan, Jason, and Melanie McBride. “Embodied Semiosis: Autistic ‘Stimming’ as Sensory Praxis.” International Handbook of Semiotics, edited by Peter Pericles Trifonas, Springer, 2015, pp. 1069–1078.

Not Locked In: Autistics Against Caudwell. “Victory! Tesco drops ‘Locked in For Autism’ Campaign & Caudwell Children Suspends It!” Change.org, https://www.change.org/p/tesco-stop-hosting-caudwell-children-s-controversial-locked-in-for-autism-campaign/u/20839921. Accessed 2 Apr 2020.

Olson, Christa J. Constitutive Visions: Indigeneity and Commonplaces of National Identity in Republican Ecuador. Penn State P, 2014.

Penney, Joel, and Caroline Dadas. “(Re)Tweeting in the Service of Protest: Digital Composition and Circulation in the Occupy Wall Street Movement.” New Media & Society, vol. 16, no. 1, 2013, pp. 74-90.

Powell, Malea, et al. “Our Story Begins Here: Constellating Cultural Rhetorics.” enculturation, vol. 18, 2014, www.enculturation.net/our-story-begins-here.

Prendergast, Catherine. “On the Rhetorics of Mental Disability.” Towards a Rhetoric of Everyday Life: New Directions in Research on Writing, Text, and Discourse, edited by Martin Nystrand and John Duffy, U of Wisconsin P, 2003, pp. 189-206.

Price, Margaret. Mad at School: Rhetorics of Mental Disability and Academic Life. U of Michigan P, 2011.

Ratcliffe, Krista. Rhetorical Listening: Identification, Gender, Whiteness. Southern Illinois UP, 2005.

Sequenzia, Amy. “The Gymnastics of Person First Language.” Ollibean, www.ollibean.com/the-gymnastics-of-person-first-language/.

@ThatGirlRea (Rea Gorman). “I’m aware the phrase ‘I am autism’ has been used to cast a negative shadow our way. I’m reclaiming this phrase. It does not belong to them. I used the phrase ‘I am autism, autism is me’ when I made my diagnosis public. This is me reclaiming those words. #ActuallyAutistic.” Twitter, 12 Sept. 2019, 6:01 p.m., twitter.com/ThatGirlRea/status/1172269082906902529.

#WalkInRed. www.walkinred.weebly.com. Accessed 18 March 2020.

Wallis, Claudia. “‘I Am Autism’: An Advocacy Video Sparks Protest.’” Time Magazine, 6 Nov. 2009, www.content.time.com/time/health/article/0,8599,1935959ffind,00.html.

Wanshel, Elyse. “People Who Are Not Disabled Need To Check Out #AbleismExists Right Now.” The Huffington Post, 22 Apr. 2016, www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/dominick-evans-ableismexists-twitter-discrimination-against-disabled-people_us_571902c9e4b0c9244a7b2eb9#.

Yang, Guobin. “Narrative Agency in Hashtag Activism: The Case of #BlackLivesMatter.” Media and Communication, vol. 4, no. 4, 2016, pp. 13-17.

Yergeau, M. Remi. Authoring Autism: On Rhetoric and Neurological Queerness. Duke UP, 2018.

---. “Clinically Significant Disturbance: On Theorists Who Theorize Theory of Mind.” Disability Studies Quarterly, vol. 33, no. 4, 2013.

---. “Disable All the Things: On Affect, Metadata, and Audience.” Computers and Writing Conference, 2014, Washington State University, Pullman, WA. Keynote Address.

---. “Occupying Autism: Rhetoric, Involuntarity, and the Meaning of Autistic Lives.” Occupying Disability: Critical Approaches to Community, Justice, and Decolonizing Disability, edited by Pamela Block et al., Springer, 2016, pp. 83–95.