Where the Visual Meets the Verbal

Robert Miltner

continued . . .

![]()

Robert Creeley: The Poet as Collaborator

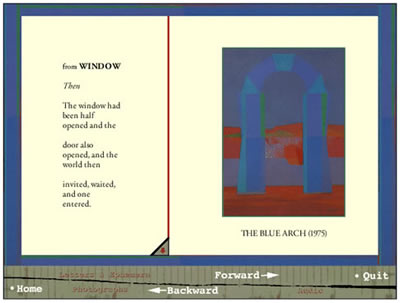

Poet and art critic John Yau, in his essay "Active Participant: Robert Creeley and the Visual Arts," views Creeley as holding a special place among Twentieth-Century American poets. Partly this is due to Creeley's role as student and teacher at Black Mountain College, where, because of the college's interdisciplinary focus, Creeley's earliest publications were ekphrastic collaborations. As a result, three of Creeley's first six books were collaborations with artists (The Immoral Proposition with drawings by Rene Laubies, All that is Lovely in Men with drawings by Dan Rice, and If You with linocuts by Fielding Dawson, Creeley's second, fifth, and sixth books of poems, respectively). Thus, in the first years of postwar American poetry, Creeley began a dialogue with the concurrent developments in postwar American art, and, in doing so, "he began making his first connections between writing and the visual arts, as well as dissolving whatever aesthetic boundaries are thought to separate the two" (Yau 52). Overall, Robert Creeley has collaborated on over forty books with diverse visual artists including Susan Rothenberg, Robert Indiana, and Jim Dine, and in books which include such mediums as lithographs, screenprints, monotypes, prints, photographs, cartoons, etchings, drawings, mezzotints, photogravures of paintings, and sculptures.

For Creeley, this creates an active dialogue between the visual artists and himself, one which enriches each artist as well as constantly expanding the discussion on the arts in general, regardless of the specific medium or individual artists involved in the collaboration. And it is this focus on the specifics of each collaboration which engages Creeley most fully, for

. . . in order to ensure that an active dialogue does occur, [Creeley] focuses his writing on what he regards as both specific and essential to the artist's work. In this regard, collaboration becomes for Creeley a way to constantly challenge himself, to consciously face the limits of what he has already done, in order to extend beyond them in some way. (Yau 48)

Facing the limits and extending beyond them is a kind of transgression, then, a crossing over borders into new territory, new landscape, new artistic opportunities. Additionally, according to Yau, because Creeley and the artist with whom he is working on a particular collaboration have agreed in advance to work toward "a mutually agreed-upon goal," the collaboration, with its "responses discovered during the process" (48), allows Creeley to "develop, explore, and maintain an open-ended dialogue with a visual artist about a common goal, reflect[ing] a strong communal impulse" (49). Further, because Creeley's collaborations are mutual exchanges, communal conversations among members of the tribe, Yau believes that Creeley, more than any other American poet, has "deflated the Modernist ideal of the artist or poet as heroic or isolated individual," replacing it with a "conscious and conscientious subversion of [the Modernist] tradition into a very different, postmodern possibility, one that doesn't privilege one form of art over another" (49). The result is a dialogue in which no one voice is louder or more powerful than another; instead, each contributes to the discussion, and each is viewed equally by the reader or viewer, engaging them in the conversation as well.

|

Copyright © Enculturation 2001 |